Why is Cecil Rhodes such a controversial figure?

- Published

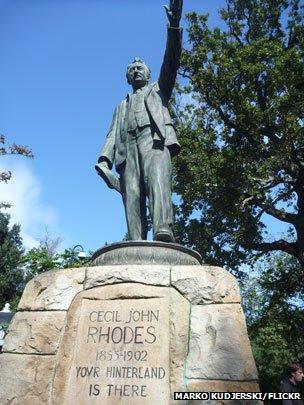

Protesters in South Africa are calling for a statue of Cecil Rhodes, one of the most committed imperialists of the 19th Century, to be taken down. Why does he still inspire such strong feelings?

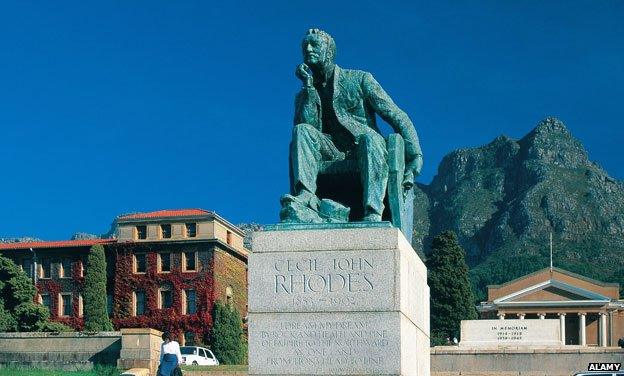

Cecil Rhodes's statue on the steps of the University of Cape Town has now been boarded up. The university will soon make a final decision on the statue's fate.

The students calling for its removal have already attacked it. The tag #RhodesMustFall has been tweeted many times.

Rhodes was an imperialist, businessman and politician who played a dominant role in southern Africa in the late 19th Century, driving the annexation of vast swathes of land.

He founded the De Beers diamond firm which until recently controlled the global trade. Scholarships allowing overseas students to come to Oxford University still bear his name. Many institutions, including Cape Town University itself, benefited from his largesse. Both Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) were named after him.

But in 2002, when the BBC conducted a poll on the 100 greatest Britons, Rhodes failed to make the list. That was despite it being the centenary of his death.

Those who want the statue removed object to Rhodes as the ultimate representation of colonialism.

Adekeye Adebajo, executive director of South Africa's Centre for Conflict Resolution, and a former Rhodes Scholar, has said the demands, external to remove the statue appear to be "a metaphorical call for the transformation of the university's curriculum, culture and faculty, which many blacks feel are alienating and still reflect a Eurocentric heritage".

Rhodes' detractors see him as a racist, and one of the people who helped prepare the way for apartheid by working to alter laws on voting and land ownership. In Zimbabwe, there are still calls to have Rhodes's remains moved, external to the UK, where he was born.

In South Africa, which has large disparities in wealth between ethnic groups, external, discussion of Rhodes has become strongly linked in recent weeks to a wider social debate.

"It is that statue that continues to inspire [white people] to think that they are a superior race," Julius Malema, leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters, describing itself as an anti-capitalist and anti-imperial organisation, has said, "and it is through collapsing of these types of symbols that the white minority will begin to appreciate that there's nothing superior about them."

It's clear that Rhodes thought of the English as a "master race".

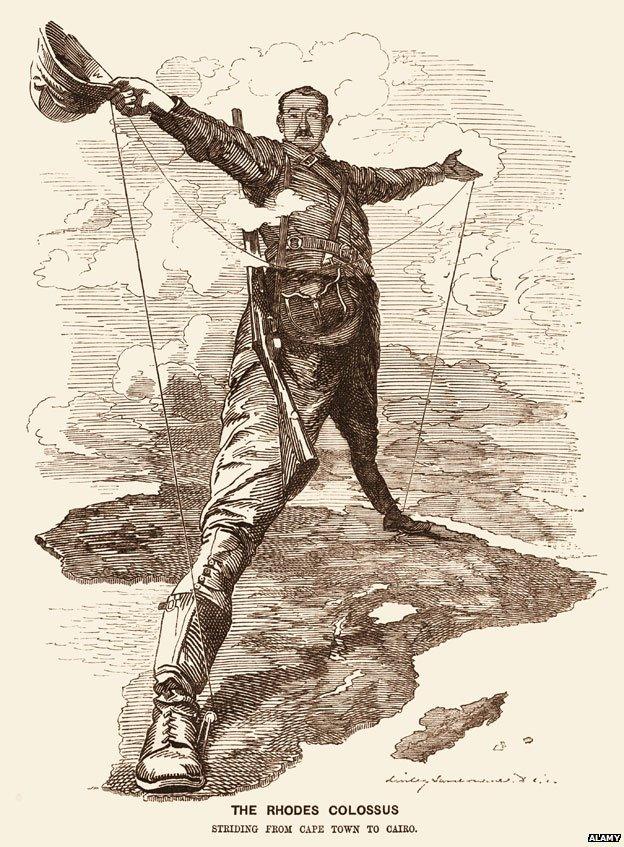

"I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race," he once said. His famous desire was to be able to draw a "red line" from Cairo to Cape Town, building a railway across the entire continent of Africa without ever leaving British territory.

Rhodes wanted to create an international movement to extend British influence.

"Why should we not form a secret society with but one object," he once said, "the furtherance of the British Empire and the bringing of the whole world under British rule, for the recovery of the United States, for making the Anglo-Saxon race but one Empire?"

His supporters saw him as having brought political and physical infrastructure to South Africa. But the critics now point to his time as prime minister of the Cape Colony, from 1890 to 1896, when his government effectively restricted the rights of black Africans by raising the financial qualifications for voting. At the same time he once reportedly said: "I could never accept the position that we should disqualify a human being on account of his colour."

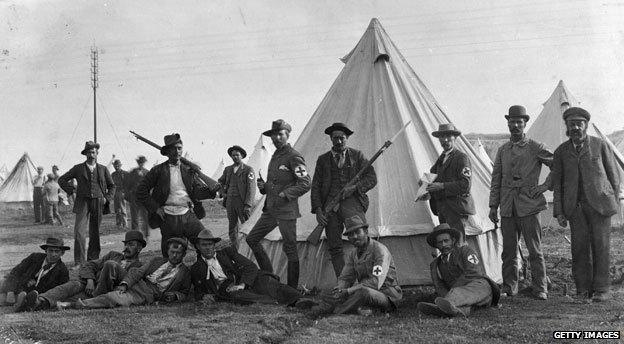

He was controversial back in Britain even at the height of his influence. Arguably his most notorious moment was his backing of the disastrous Jameson Raid of 1895, in which a small British force tried to overthrow Paul Kruger, the Afrikaner president of the gold-rich Transvaal Republic. The raid helped prompt the Second Boer War, in which tens of thousands died.

"At best his conception of civilisation was empirical, if not vulgar," the Guardian noted in its obituary, external of Rhodes, "and in course of time most other ideals had for him to be subordinated to that of keeping up dividends."

Apartheid was introduced in 1948 and ended in 1991, but it has taken until now for there to be momentum behind removing statues of Rhodes. "I'm surprised that [the protesters] have come up with this at the moment," says Berny Sebe, author of Heroic Imperialists in Africa, a study of the enduring influence of Rhodes and others. "The year 2002, the 100th anniversary of his death, would have been a more obvious date."

But the targeting of the statue has in fact been going on for years, says Saul Dubow, professor of African history at Queen Mary University of London, and a former student at Cape Town. "I suspect he's become a soft target," he says. "The university authorities aren't going to defend Rhodes."

Rhodes is disliked by most black South Africans, Afrikaners and those of British heritage, Dubow suggests.

Law lecturer Pierre de Vos, who works at Cape Town University, thinks the timing is significant. "Ultimately, it seems to me the protesters are calling on us to recognise the uncomfortable strangeness of our country," he has written, external, "a country hovering halfway between a past from which it cannot escape and a future its citizens are too scared, filled with self-doubt or complacent to re-imagine and recreate in their own image."

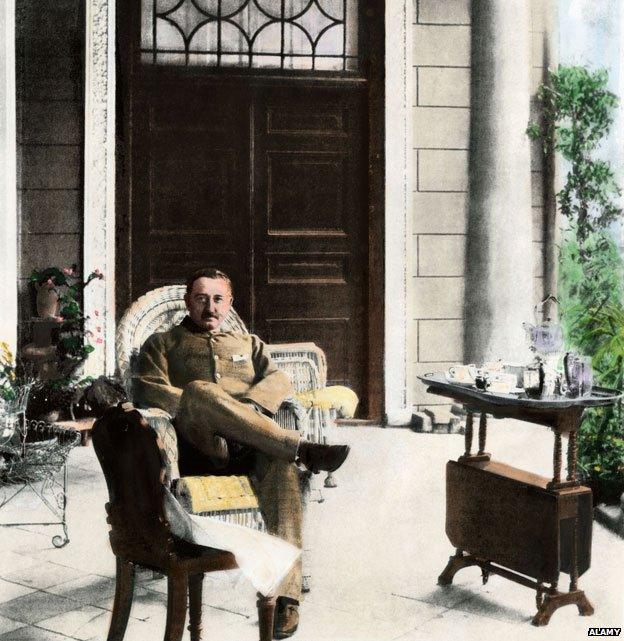

Rhodes, born the son of a vicar in Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, in 1853, was dogged by ill health as a child. He first came to Africa, where the climate was deemed better for him, aged 17. He grew cotton in Natal, but moved into diamond mining, gradually outwitting his rivals to become the dominant force in the trade.

The reason Rhodes's statue sits at the centre of the University of Cape Town's campus is that he bequeathed the land on which it was built.

Another of the reasons his name is well known today is the Rhodes Scholarships created via his will. These allow 83 students from the United States, Germany, Hong Kong, Bermuda, Zimbabwe and several Commonwealth countries - including a number of southern African nations - to come each year to Oxford University. Former US President Bill Clinton is probably the best known of the scholars.

Many buildings still bear his name, as does Rhodes University, set up in 1904 in Grahamstown, South Africa.

Few leaders in the countries affected by Rhodes, including Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, have chosen to dismantle monuments to him, notes Sebe.

"Whether derided or praised," the historian Robert Rotberg has written, "he remains an object of calumny, obsequy and inquiry."

Rhodes said in life that he wanted to cheat the constraints of mortality by leaving a legacy.

His tomb remains untouched. The statue still stands, at least for the time being. But once again, Rhodes is at the centre of discussion.

The Jameson Raid

In 1895 Rhodes instructed British colonial statesman Leander Starr Jameson to invade the Transvaal from the British-controlled Cape Colony in an attempt to overthrow the government of President Kruger. The raid failed

Rhodes wanted a united South Africa and a Cape to Cairo Railway running through British territory all the way. Kruger wanted the Transvaal to remain Afrikaner

Kruger and the Boers felt their way of life was threatened by the British and war broke out in 1898

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.