24 hours in a fuel tank

- Published

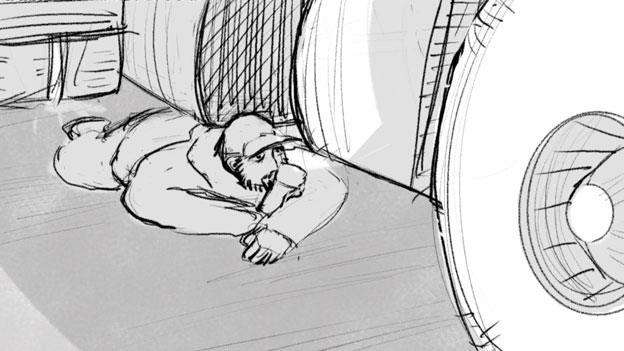

Badi explains how he Anas and Said survived

Three refugees from the war in Syria met in Turkey and crossed into Greece - but they wanted to go further. With money running out and their families in Turkey relying on them to find a new home, they made a last-ditch attempt to get into Italy. Said tells their story.

We knew the fuel tank was a bad way to go. There were Syrian guys who had tried it before and they all said, "Don't do it!"

But we were desperate to get out of Greece. I'd been stuck there for two months, living in a flat in Athens with Anas and Badi. There was no work, no help, no way to survive. The police were hassling us every day, aggressive as hell. "Where are your papers? Where are your papers?"

The traffickers sat around in the cafes, Kurdish and Arab guys mainly, talking quite openly about the ways they could get people into other Western European countries. By plane. By boat. In the fuel tank of a lorry.

The fuel tank was the worst, but it was a surefire way to get in. "You might be a corpse by the time you arrive," they said, "but you'll get there."

Many lorries have two fuel tanks, but may only need one

The guy who told us about the lorry was an Egyptian who ran an internet cafe near Omonia Square. The cafe was just a front for the smuggling operation, really. A lot of Arab kids would be in there talking to their parents on Skype, and he would listen in to find out who was trying to get into France or Italy. He told us he knew a Greek driver going to Milan. For 5,000 euros (£3,630, $5,386) each, he could take four of us in the second fuel tank.

We left Athens in a taxi, me and Badi and Anas and an Iraqi guy who we didn't really know. The driver took us to a warehouse in an industrial zone outside Thessaloniki, not far from the sea. The lorry was hidden inside and the driver shut the warehouse doors so no-one could see what was going on.

He told us all to go to the toilet before we got in. The other guys all took a leak, but I just couldn't go. I was too tense.

We had to get into the tank by crawling under the axle of the lorry and squeezing through this tiny door. As soon as I saw it I thought, "We're going to die in there."

When we'd taken a look we scrambled back out from under the lorry and prayed, there on the floor of the warehouse. We prayed for our children, all four of us together. Then we crammed ourselves into the tank and the driver started the engines.

As soon as the lorry started to move we knew we wouldn't last an hour. It was burning hot and filled with diesel fumes. Anas was frantic, banging on the tank and screaming this weird scream. The driver heard him and the lorry stopped before it had left the warehouse. We scrambled out. Anas said, "I have kids, I don't want to die."

There was no way all four of us could go in that tank, so we agreed that the Iraqi guy would go back to Athens. The rest of us had been together for months. We were like brothers. We trusted each other.

The driver was going to lose 5,000 euros, but he didn't want to arrive with a bunch of dead bodies in the tank. So he squeezed an extra 500 euros out of the three of us and we got back in.

Within an hour, I needed to pee so badly it hurt. We were squished together like dough. There was a rubber sheet on the floor of the tank and it just melted in the heat. I mean it turned to liquid. We were covered in this black stuff. It was like an oven, pitch black. It stank of melting plastic and diesel fumes. I was 100% certain that we were going to die.

We had a small plastic Pepsi bottle with us, and Badi and Anas managed to pee in it. Well, half of it went in the bottle and half of it went everywhere, all over their clothes and on to the floor of the tank with the melted rubber. Badi emptied the bottle outside the tank, but the lorry was going fast and the wind blew the spray back inside.

Where are Syrian migrants trying to go?

Said en route

Syrian refugees often enter the EU in Italy or Greece, but most would prefer to get to a country with more jobs and better social welfare. Police harassment can also be a problem.

The most popular countries are in northern Europe. The UK, the Netherlands, Germany, and the Scandinavian states are all seen as places that offer a degree of support to asylum seekers and provide migrants with a chance of finding work.

Professional migrant smugglers operate all over Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Some advertise their services and answer enquiries on Facebook.

Desperate migrants often pass huge sums of money, saved over years of work or borrowed from families, into the hands of criminal smuggling gangs.

By then I was really in agony, but I just couldn't pee in that bottle with my friends there. Towards the end of the journey the pain was so bad that I was actually blacking out. I tried to keep quiet for their sakes, but all the way I was screaming inside.

After a while the lorry drove on to a ferry. Without the engine noise we were scared they'd hear us, so we never said a word except when the lorry was going fast. We just stayed there silently, listening to the boat's engines and struggling to breathe.

None of us thought we'd make it. I had my mobile in my hand and I kept looking at the screen in the darkness, looking at photos of my wife and my girls. I have twin girls, Deema and Reema. They're four years old. I did this whole journey just for them. I left Syria to get my girls out of this war. I just kept thinking, "How are they going to survive if I don't make it?"

We had another girl on the way, too. I'd already seen the ultrasound in Turkey, so we knew it was a girl. I just lay there looking at my family on the phone and wondering if God would give me life to see that baby.

In the end the battery died.

Finally the engines started again and we started to move, slowly slowly slowly. When we stopped we could hear men talking loudly outside - "Buongiorno! Grazie! Prego! Grazie!" - and we knew we were in Italy. We were relieved, because whatever happened we would not be sent back to Greece.

The driver was supposed to take us to Milan but after a few more hours we just couldn't stand it any more. We started banging on the side of the tank, yelling, but he didn't hear us or he didn't want to stop.

Badi still had some juice in his phone, so he called the trafficker in Athens from inside the tank and said, "Call the driver and tell him to let us out or we're going to die in here." Not long after that the driver turned off the big road and after a while he stopped.

We collapsed out of the tank on to the floor. We couldn't unfold our legs, couldn't even feel them, so we had to drag ourselves out from under the lorry with our hands. It was the middle of the day. We were in a wood somewhere in Italy.

The driver made it clear that he no longer knew us, that we were on our own. After he drove off we rolled down a slope and crawled into a concrete storm tunnel under the road. We just lay in there trying to move our limbs and to breathe. After 10 minutes, lying there on my side, I managed to take a pee.

When we got our breath back we sat up and looked at each other. And then we really laughed, because we were covered in black melted rubber and we stank. We stripped of our shirts and turned them inside out and used them to clean off the worst of it. We'd each brought a small bag with a change of clothes, so we got into clean shirts and left the old ones in the tunnel.

We had no idea where we were. Badi used the GPS on his phone to find a village, and we started walking towards it. There were vineyards everywhere, and after a while we saw farms. When cars came past we were scared that the villagers would report us to the police as they had in Greece, so we turned our backs on the cars and pointed at the scenery, acting as though were tourists out for a stroll in the hills.

When we got into the village we had to ask for help. We hadn't eaten or drunk anything for 24 hours. The other guys pushed me to the front, because I was the whitest and the most educated. I have a degree in economics, and a bit of English, and I'd learned a few Italian words before we set off. So I had to do the talking.

The Italians were so kind to us. They actually took us by the hand, physically took our hands, and led us to the restaurant. It was closed, so we went to a cafe instead.

There was nothing to eat in there. The waiter brought us coffee and water. The water was fizzy. I had never had fizzy water before, and I just couldn't drink it. So we drank the coffee. It was espresso. Black. Bitter. That was the next time we laughed. We survived the fuel tank, we said, but this coffee's going to kill us.

Said split up with Anas and Badi (the narrator of the video, above) in Italy. He took a train over the Alps and arrived in Vienna. Anas bought a fake passport from smugglers in Italy and used it to fly to Sweden. His cousin, Badi, was eventually able to join a cousin in Leeds. All three have been granted asylum.

As soon as he was settled, Said sent for his family. Almost a year earlier he'd left a wife and twin daughters in Turkey. They arrived in Austria carrying a new member of the family - Mais, the baby that Said feared he'd never see.

He told his story to Daniel Silas Adamson and Mamdouh Akbiek of the BBC World Service. Animation by Osamah Al-Rasbi, video editing by Shayma Alissi. Explore more stories from Syrian refugees.

Said with all three of his daughters, in Vienna

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.