Fatal silence: Why do so many fortysomething men kill themselves?

- Published

Simon Jack: "One January morning... my father left the family home and took his own life"

Suicide claims a worrying number of lives, with men much more at risk than women in the UK. Simon Jack, whose father killed himself, has tried to find out why.

Forty-four is a fairly unremarkable age to reach for most, but for me, it was a birthday that always had special significance. It was the age my father took his own life 25 years ago, for reasons I'm still unclear about.

As a result, I have always been sensitive to stories about suicide in the news and have noted how often it seemed to be men I was reading about.

What I didn't realise until recently was that suicide is the biggest killer of men under the age of 50. A hundred men die a week. It is more prevalent than at any time in the last 14 years and men are four times more likely to end their own lives than women.

I wanted to find out why. What is it about being a man that makes you more susceptible and what, if anything, can be done about it?

My own father, in his 40s, was in the most vulnerable age group.

Incidence of suicide peaks among men in that decade. You can guess at reasons - your wife leaves and takes the children, you lose your job at an age when it's difficult to find another. All that could heap stress on men who feel pressure to provide for their families.

In my father's case, none of that would really explain it. He was a popular, gregarious and talented man with a loving wife and four sons, of whom I was the eldest. I have also been struck that so many families feel at a loss to explain why any of these factors would end in the extreme of suicide rather than just hardship or divorce.

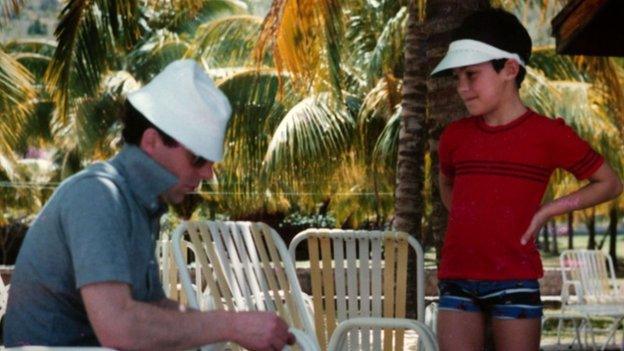

Simon on holiday with his father

I turned first to Samaritans, whose research is based on 60 years of experience. Their work highlights a complex set of factors - including financial and emotional problems, personality traits, the challenges of mid-life and mental health issues.

It struck me that all of these affect women too. So why is it that although half the calls Samaritans receive come from women, four times as many men end up dead?

There's also a commonly held view that suicide is evidence in itself of mental illness. The argument is that to do it, you have to be suffering from a diagnosable mental illness such as depression.

Prof Rory O'Connor runs one of the world's leading research centres into suicide at Glasgow University and conducts experiments into the psychology of suicidal behaviour. Mental illness is often a part of the problem but isn't sufficient as a complete explanation, he says.

"We think that most people who die by suicide have a mental illness but less than 5% of people with a mental illness take their own lives."

Are you affected by this?

Samaritans provides emotional support, 24 hours a day for people who are experiencing feelings of distress or thoughts of suicide

Its number is 08457 90 90 90

Rethink Mental Illness has more than 200 mental health services and 150 support groups across England.

Its number is 0300 5000 927

I needed to know more about what was going on in my dad's life and that meant a long overdue talk with my mum. This was a daunting prospect as, in the intervening years, the subject has almost never been raised.

This in itself is a key part of the problem for many families. My brothers and I found it too upsetting to discuss, too likely to induce embarrassing tears or cause family arguments.

Despite reservations on her side, and deep misgivings on the part of my three brothers, my mum bravely agreed for our talk to be filmed. In that session I found out about affairs my dad had been having - most of which, like the financial problems he was facing, emerged after his death and were not discussed before.

These sorts of problems might help explain the high rate of suicide in fortysomething men, but suicide is also the biggest killer of those aged 20-34, accounting for nearly a quarter of all deaths.

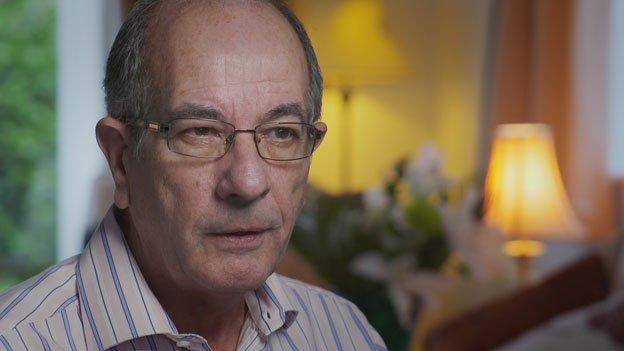

I spoke to Stephen Habgood, chairmain of the charity PAPYRUS Prevention of Young Suicide, external, whose son died when he was 25. Again an outgoing and popular young man, Chris's death was a total shock to his father and stepmother.

"He was so personable, he looked good, he looked smart, he was very articulate, he seemed very confident," says Stephen.

Stephen Habgood

But however articulate he may have been, Chris never discussed his state of mind with his family. Stephen is convinced that this inability or unwillingness in men of all ages to talk is the key to explaining the huge imbalance in male and female suicide rates.

"He didn't want me to know that he was struggling inside. He wanted me to think that he was coping, that he was strong."

There's a useful thought experiment that can illustrate this, says Joe Ferns, executive director of policy at Samaritans.

"If you came into work on a Monday morning, and perhaps there's somebody in the office who's upset, something's happened over the weekend and they're crying. I'd put it to you that if that was a woman, if that was a female colleague, that what would happen is somebody would gather that person together, take them off to the toilets and they'd have a chat and come back and probably little would be thought of it.

"If you come into the office and find a man crying at his desk, I suspect that the reaction of the people around that person is far more dramatic. People assume something really bad must have happened."

More from the Magazine

"Have you got children? It's a standard dinner party question, often an area of common ground. But it's a question that I find hard to answer," says Dick Moore. His son Barney took his own life in 2011. "Waves of grief still roll in from time to time and there isn't a day that goes by that a memory is not stirred, a wistful thought provoked by a smell or a song or a photograph," he says. "But we are OK. We have survived and, perhaps oddly, we are able to enjoy life again."

There is a difference between the way that we react to men and women expressing the way that they feel.

So can simply talking really save lives? Matt was one of the people I met who thought about killing himself and didn't. He felt desperate because he didn't feel he fitted in with ideas of what it meant to be a man in his community.

"I've always been quite an expressive person, I've always been into art and things like that and it's sort of, been quite effeminate, maybe.

"It didn't really fit in with my group of friends so I always felt like an outsider looking in. And that was obviously difficult because when you're growing up, nobody likes to be the outcast, do they?"

Having decided he was going to kill himself, Matt happened to walk past the Samaritans office in Oxford Road in Manchester, thought there was nothing to lose and went in. He now acknowledges that decision saved his life. He had always put off doing it before.

"The major thing that put me off talking to somebody was this idea of weakness. If you couldn't sort your problems out yourself, then you were a weak person."

That perception is central to understanding why men take their lives in such shocking numbers, says Jane Powell, chief executive of the Campaign Against Living Miserably or CALM, external.

"It's boiled down to the one thing they can be, should be, is strong. And if we're going to add anything to that, it's silent. And the phrase that comes back is to 'man up', to 'grow a pair'."

If it's macho images of men you are looking for, then northern professional Rugby League has them in abundance. And yet, I found attempts to tackle these stereotypes thriving in this most unlikely place.

Ian Knott was a successful professional player for Warrington Wolves when he suffered a career-ending back injury that has left him in constant physical pain. His inability to perform many of the roles he considered part and parcel of being a player, husband and father, led him to an attempt on his own life.

Ian Knott was a rugby player for Warrington Wolves: ''I can talk about my experiences... and hopefully help other people''

"The pain got to such a point where I just did think to myself, 'what's the point of me being here?' My wife and my kids are still there, you know, but I just didn't want to be a part of it.

"I'm proud of myself now because now I can go around and I can talk about my experiences and hopefully help other people, and especially other men.

"That is the main problem with men. They don't open up. And they've got absolutely nothing to be ashamed of."

Ian now regularly speaks at meetings held by State of Mind, an organisation that screens classic sports matches, invites former stars to talk about their careers and acts as a forum for sharing difficult thoughts and feelings. I went to one of their meetings and it was well attended, warm, open and at times very moving.

Making a film on this subject was an unusual and personally challenging project. But it proved enormously helpful to me, my family and I hope our contributors.

The number of people who die this way is shocking. There are no easy answers and the conclusion I took away is simple but important. It is summed up in a poster produced by the charity CALM which simply reads - the Strong, Silent, Dead type.

Wherever I went, I found people who, once they found out what I was filming, suddenly came forward with their own stories. A total stranger who I now know as Dave, who I met by chance filming in a pub in Warrington, revealed that his father had killed himself when he was eight. He said he had rarely had a chance to talk about what happened.

"You know what it's like, even with your mates; suicide is a conversation stopper not a conversation starter."

For that to still be true about the biggest killer of men under the age of 50 is unacceptable and needs to change.

A Suicide in the Family will be shown on Panorama at 20:30 BST on BBC One, 13 April 2015 - or catch up on iPlayer

How you can seek help - If you are feeling emotionally distressed and would like details of organisations which offer advice and support, go online to bbc.co.uk/actionline.

Rethink Mental Illness has more than 200 mental health services and 150 support groups across England. Its number is 0300 5000 927.

Samaritans provides 24-hour emotional support for people who are experiencing feelings of distress or thoughts of suicide. Its number is 08457 90 90 90.

Papyrus works with young people to prevent suicide. Its helpline number is 0800 068 4141

Yana (You Are Not Alone) offers help for those working in farming who are affected by stress or depression. Its number is 0300 323 0400.