Russia's most daring theatre company

- Published

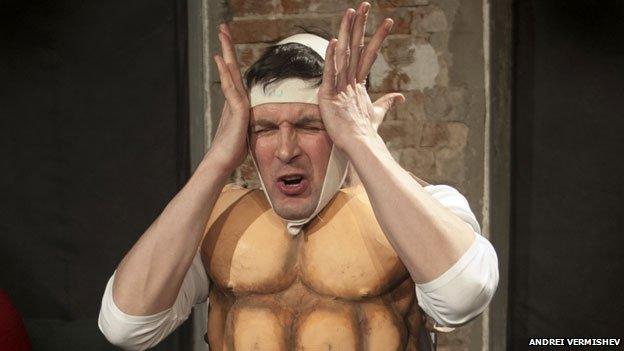

BerlusPutin imagines Silvio Berlusconi's brain in Vladimir Putin's body

A fearless Russian drama company has risen from the dead after being evicted from its premises in Moscow this winter. The eviction seemed at first to be a political death sentence, but does a theatre with barely 100 seats really present a threat to the Kremlin?

Just down the street from Moscow's pale blue Yelokhovskaya Cathedral, there is a small, one-storey building behind a gate. Attached the the railings, I read a hastily written cardboard sign with an arrow pointing to the courtyard.

This is the new home of the embattled Moscow drama company Teatr Doc. Inside is a hive of activity in preparation for the re-opening - one man on a stepladder is attaching some lights to a beam as people below him stack chairs and mop the floor.

It still looks a bit like a building site, and plaster dust hangs in the air as I walk into a little side room where a young bearded man is awkwardly holding a hammer.

Aleksey Krizhevsky, whose day job is writing for a news website, is doing his best to put up coat pegs. He is one of an army of volunteers who have come to clear rubble, lay bricks, sand and paint over the past six weeks.

Actors, directors, students and members of the audience have all lent a hand, he says.

"We never went hungry because people kept bringing in sandwiches and home cooked food. It was a great atmosphere."

When the Moscow government threw Teatr Doc out of a basement in the city centre where it had worked for 12 years, the homeless company appealed to its audience for help.

Oleg Karlsson, an architect, was one of hundreds who responded to SOS messages on Facebook. He donated his time and expertise to turn a semi-derelict structure - once part of an 18th Century nobleman's estate, and later a fish shop - into Doc's new base.

"I've done what I can to turn these ruins into a useable space," he says, "but we need three or four times the funds to do it properly."

The new premises - a former fish shop

The basement near Pushkin Square - now welded shut

The old premises of Teatr Doc were located close to the fashionable Pushkin Square, but the doors and windows are now welded shut with sheets of metal.

The company rented the venue from the Moscow city government but had its lease revoked last autumn, supposedly for violating planning regulations by installing an extra emergency exit - work it undertook on the orders of the fire brigade.

Tax inspectors, firemen and police are often used to close down businesses and get rid of undesirable tenants. Teatr Doc was was able to remain in situ, however, while it appealed against the eviction.

Then, one evening in December, as it started screening clips from a documentary on the political turmoil and bloodshed in Ukraine, police from a special anti-extremism division burst in and marched everyone out into the courtyard.

At first they said they had received a bomb threat.

"They spent ages checking our IDs outside and we were asking if there really is a bomb why do you keep us here? All of us could die if it explodes! " says Aleksey Krizhevsky, who had been one of two dozen people in the audience.

"It was strange because an official from the Ministry of Culture and a policeman just sat in the theatre for hours watching the whole film as we stood shivering outside in -15C!"

Yelena Gremina, a renowned playwright and the director of Teatr Doc, was out of town at the time but got a call to say that three people from the theatre had been arrested and that laptops and other material were being taken out of the office.

Find out more:

Listen to Lucy Ash's radio documentary for Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4 on the BBC iPlayer

Elena Gremina: "We believe in freedom of expression"

"The place had been ransacked," she says. "They'd kicked a door in, you could see their bootmarks all over it - they trashed the office and dressing room, scattered make up on the floor, smashed up our scenery - it was awful."

An inquiry dragged on for two weeks before a case of extremism opened against the theatre, and against her personally, was dropped.

"Of course, there was nothing extremist about any of the stuff we do - we just believe in freedom of expression," she says. "But the next day people from the Ministry of Culture called me in to warn that next time we'd be punished more severely."

Gremina, a woman with a mop of curly hair and fierce black eyes, refuses to be intimidated.

"Whoever cooked up this idiotic scenario had clearly bitten off more than he could chew," she says.

Teatr Doc has made its mark by reflecting the unvarnished reality of everyday life in Russia.

It was founded in 2002 by a group of writers who couldn't find a theatre willing to stage their documentary-style writing. Practically all its plays are verbatim, created on the basis of long interviews with actual people.

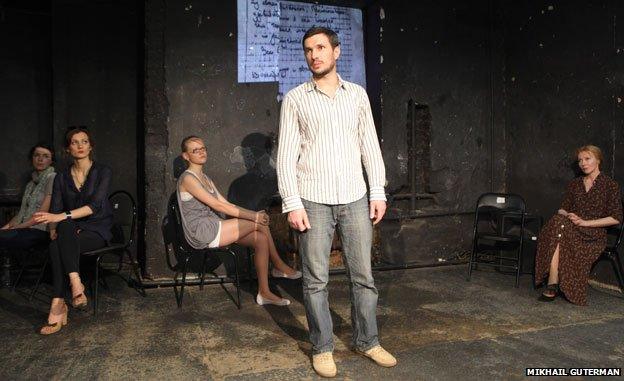

Anna Kotova, a young actress who has appeared in a number of its productions, says Teatr Doc calls itself "the theatre where nobody acts"- though preserving the exact speech of interviewees can be more challenging than reciting the dialogue of classical Russian theatre or TV comedy, she says.

At the packed-out opening show in the new building, one of the first on stage is Marina Kleshova, who has spent most of her life behind bars.

Anna Kotova (right): It's "the theatre where nobody acts"

Marina Kleshova began to work with Teatr Doc after the company visited her penal colony

"I'm not afraid of Teatr Doc and it is not afraid of me," she says, walking on with her guitar.

She performs a Soviet-era lament about New Year's Eve in a penal colony which, much to the audience's delight, contains a number of powerful swear words. The song defiantly puts two fingers up to a recent law which bans obscene language from stage and screen. There are cheers and whistles as she sings in a throaty voice and strums her guitar.

At first, Teatr Doc's playwrights and directors focused mainly on social issues such as the plight of prisoners, migrant workers, drug addicts and people treated like outcasts after being infected with HIV.

But from 2010 onwards, the plays became more critical of the government, says John Freedman, a Moscow-based translator, writer and specialist on Russian theatre.

"Everybody started to sense that there was a clamping down, a growing conservatism, and in response they started doing more political shows," he says.

One play which may have irritated the authorities was about the whistle-blowing lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, who accused tax officials and police officers of embezzling $230m. Shortly afterwards, he was arrested and died an agonising death in custody. Based on interviews and court transcripts, the title of the play One Hour and 18 Minutes refers to the period of time that medical treatment was denied to Magnitsky in his cell.

"The play showed how incredibly callous all of the policemen were, as well as the guards, the judges and the medical staff," says Freedman. "It was the story of a man simply hounded to death because he had information about government corruption."

Russia's president is savagely lampooned in another even edgier Teatr Doc production, BerlusPutin, a farce adapted from a play by the Italian satirist Dario Fo, called the Two-headed Anomaly. In Doc's version, Silvio Berlusconi's brain is transplanted into the head of Vladimir Putin with disastrous results.

The actor playing Putin wears a rubber chest - mimicking the naked torso which the real President regularly flaunts on Russian TV. He later dons a mask of Dobby the house elf, a character from the Harry Potter movies. It seems the botox treatment to get rid of the president's wrinkles has gone badly wrong. But slapstick aside, the play contains some altogether blacker humour.

Sergei Yepishev and Milena Tskhovreba in BerlusPutin

The play revolves around the relationship between Vladimir Putin and his former wife Lyudmila, who has been dumped in a monastery. When he suggests they have sex, she yells: "You can't rape me, I'm not Russia!"

How much can Teatr Doc get away with?

Russia has a constitution, which officially protects artistic freedom. But with war in Ukraine, and a plunging rouble, these are uncertain and increasingly intolerant times. Nationalism is on the rise, as is the influence of the Russian Orthodox church.

Just after the re-opening in February, I met Sergei Kapkov, the man in charge of culture in the Moscow city government, who brought wi-fi and rental bikes to Gorky Park, renovated theatres and, unusually, earned the support of the liberal opposition.

He told me the Russian capital was a "thriving metropolis filled with creative people who have many different points of view" and that he would not interfere with Teatr Doc "so long as it stays within the law".

So, I insisted, can a theatre which is critical of the government and even of the president himself survive in today's climate?

"I'm not Nostrodamus," he snapped. "I can't see into the future."

A few weeks later, Kapkov stepped down.

The reasons for this unclear, but many saw his resignation as a bad omen. He certainly seemed to have a far more liberal vision than Vladimir Medinsky - Russia's hardline Minister of Culture.

The Russian movie Leviathan won prizes at Cannes and the Golden Globes but the film - about a corrupt local mayor who forces a family off their land - was not to Medinsky's taste.

Such "negative" films, he said, would never again receive official funding.

Since then Medinsky has waded into a row over the staging of Wagner's opera, Tannhauser, in the Siberian city of Novosibirsk - sacking the manager of the opera house after Orthodox clerics objected to scantily clad Biblical characters. The production was "humiliating" to believers, the clerics said - the same argument used to jail members of Pussy Riot after their punk performance in a Moscow cathedral.

Thousands protested last month against the Novosibirsk Tannhauser production

But Teatr Doc still revels in pushing the boundaries - it has just hosted a one-man show from Kiev based on the diary of a military psychologist who counsels Ukraine's frontline troops. The evening wasn't advertised for fear of another visit from the police.

Next month it will premiere a play about the Bolotnaya Square demonstration of 2011, when tens of thousands protested against Vladimir Putin's return to the presidency for a third term. The work is based on interviews with the families of demonstrators who ended up in jail.

Teatr Doc may be small, its productions are not televised and you can only watch fragments online. But it has an impressive reach both outside and inside the country.

And even a small independent theatre is important, says director Elena Gremina. People across Russia have been watching carefully over the last few months, she says, wondering whether Teatr Doc will surrender or not.

"When we were gathering money for our new building online," she says, "we received small donations of 200 or 300 roubles (less than $5) from people living in Blagoveshchensk, Nizhniy Novgorod and Novosibirsk - thousands of miles away. They might have never visited our theatre but it's important for them to know that we exist."

Listen to Lucy Ash's radio documentary for Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4 on the BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.