Gallipoli: Six tales of valour and a missing Victoria Cross

- Published

Six Victoria Cross medals were won by one regiment on the first day of the Gallipoli campaign. But they had never all been in the same room - and one appeared to have disappeared altogether. It took a feat of detective work to bring them together at last.

Collectively, they were known as the "six VCs before breakfast". These Victoria Crosses - the highest UK and Commonwealth military honour there is - were awarded for valour shown by soldiers from the Lancashire Fusiliers in a famously bloody dawn assault near Cape Helles, Turkey, on 25 April 1915.

It was the opening salvo in the ultimately doomed Gallipoli campaign of World War One, which resulted in more than 100,000 deaths among British, Australian and New Zealand troops, plus allies from other nations on one side, and the Turkish troops of the Ottoman Empire on the other.

The VC citation describes the hail of deadly machine gun fire the Fusiliers faced while landing at W beach, and how they overcame supreme difficulties to cut the barbed wire entanglements under fire and gain control of the cliffs above the beach.

The citation reads: "Among the many very gallant officers and men engaged in this most hazardous undertaking, Captain Bromley, Sergeant Stubbs, and Corporal Grimshaw have been selected by their comrades as having performed the most single acts of bravery and devotion to duty."

They had gone down in Army folklore, but the six VCs had never been together in the same place.

Two of the six were already on display at the Fusiliers Museum in Bury, Lancashire, and three more were owned by Lord Ashcroft, an avid collector of war medals, and on permanent display at the Imperial War Museum in London.

Then there was the sixth VC, which was missing and hadn't been seen in public for the best part of a hundred years.

Tales of bravery

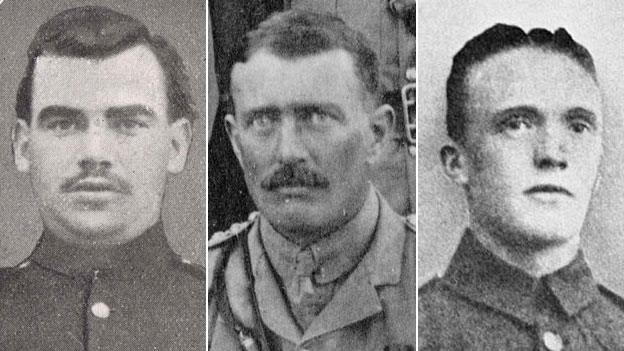

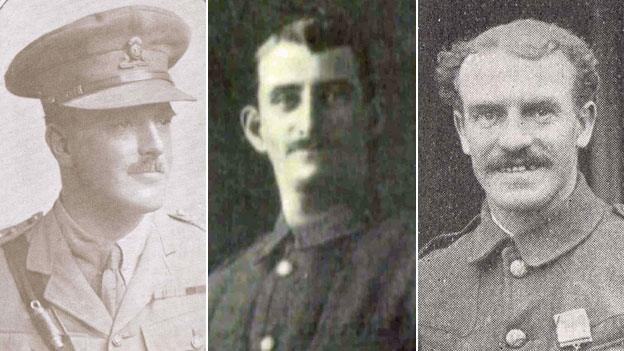

Pte William Kenealy, Maj Cuthbert Bromley and Cpl John Elisha Grimshaw

Pte William Kenealy, 1886 - 1915 When his company was held up behind barbed wire he volunteered to crawl through the wire and attempt to cut it. Though unsuccessful - due to faulty cutters - he was promoted to L/Sgt. He was killed at Gully Ravine on 28 June.

Maj Cuthbert Bromley, 1878 - 1915 He was the adjutant to the Commanding Officer at Gallipoli and was shot in his back on the first day. He refused to leave his men, only reporting the wound three days later, after receiving a further wound in his knee. Promoted to Maj he led his men during the battles of Krithia before being badly wounded in the foot at Gully ravine, refusing to leave his post until the battle was over. After a spell in hospital in Egypt he managed to get onto the troopship the Royal Edward to return to Gallipoli but was killed when the ship was sunk in the Aegean Sea. He was seen helping people, before being hit on the head with driftwood and drowning.

Cpl John Elisha Grimshaw, 1893 -1980 His role was to maintain contact between the HQ on board HMS Euryalus and the units on the ground. During the landing and the fighting on hill 114, urging his fellow soldiers on when they faltered under fire. Grimshaw's water bottle and backpack were riddled with bullets and his cap badge was smashed - but he escaped any injury.

It was Sarah Stevenson, collections officer at the Fusiliers Museum, who first came up with the idea, three years ago, of getting all six together at the museum for the 100th anniversary celebrations of the campaign.

But this was no easy task - even before the missing VC could be located. None of the war medals had ever been loaned out elsewhere before, and initial approaches to the Imperial War Museum were rebuffed.

Undaunted, displaying the sort of can-do attitude you'd expect from a 30-year veteran in the Army, Col Brian Gorski, chairman of the Fusiliers Museum, took up the task of hunting down and acquiring the missing VC with gusto.

"At one moment of time I thought we'd never get there, when everything went dead for two or three months," he admits, "I thought, I'm going to give this whole thing up."

He began his search with what little was known about the recipient of the missing VC, awarded posthumously to Capt Cuthbert Bromley.

At Gallipoli, Capt Bromley was shot in the back and the knee, but carried on fighting. Later he was hit by shrapnel in the ankle. He died the following August, when the troopship he was on, the Royal Edward, was torpedoed and sunk in the Aegean Sea with the loss of almost 1,000 lives, while sailing back to Gallipoli from hospital in Egypt.

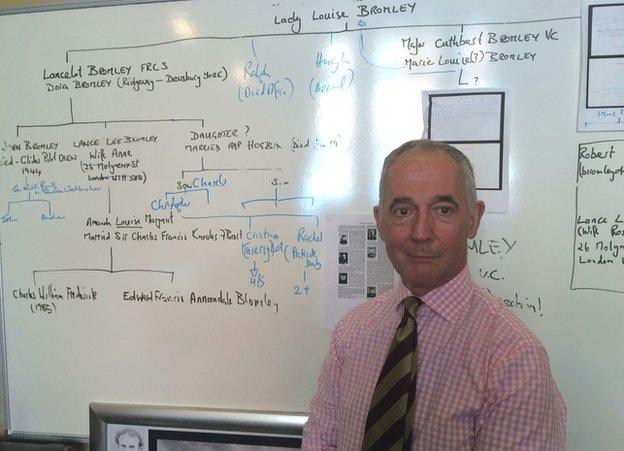

Col Brian Gorski helped track down the lost medal

Col Gorski showed me the makeshift Bromley family tree he began compiling on a whiteboard in the museum office, working on the assumption that someone in the extended family still owned the VC.

Using public records, and by trawling archives in East Sussex where the family originated, he traced each family line down from Cuthbert's three brothers and a sister. He even searched graveyards in Sussex, and visited old addresses, in what seemed at first like a fruitless task.

At one point during the search, Stevenson appeared on BBC North West Tonight, appealing to anyone who knew of the whereabouts of the VC to come forward.

"It was a long and eventful journey," says Col Gorski. He eventually discovered family members still living in the same area where Cuthbert Bromley had lived - including a cousin, Louise Bromley.

Email exchanges eventually led to another cousin of Louise, Nick Bromley, who lived in London. Crucially, Nick owned Cuthbert's Victoria Cross. It was sitting in its presentation case on his sideboard.

At first Nick was surprised to have been contacted, but then he remembered the anniversary. "I was very honoured that we'd been approached," he says. He thought it was only right that the medals should be reunited for the occasion.

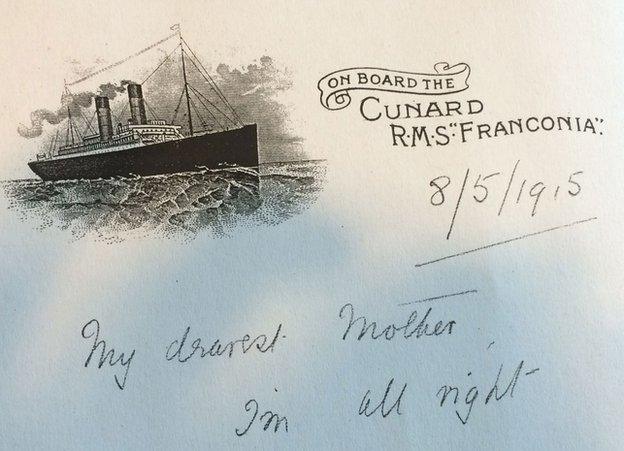

Nick showed me various letters which the family had kept, written by Capt Bromley to his mother, another Louise Bromley, from the battlefield at Gallipoli.

On yellowed paper, and written in pencil, faded after 100 years, they give a tantalising, fascinating and somewhat quirky insight into life during the battle.

29 April 1915

My Dearest mother,

I'm laid up with a bullet wound, nothing serious at all, clean through the flesh and I'm as fit as can be. The regiment suffered rather heavily in the recent fighting. I quite enjoyed myself and hope to be about again very shortly. Fondest love, Cuthbert.

PS Writing bad is not due to wound but awkward position lying down.

3 June 1915

My Dearest Mother,

I got your letter of 6 May. Very fit. We're close up to brother Turk now. Only fifty yards away in places. The show has changed from open work to trench warfare. But we shall get them out soon. Lovely climate here and sea bathing. I hope all goes well at home.

Fondest love to you and Mary. Cuthbert.

14 June 1915

My dearest Mother,

Here we are again. I'm in command now until someone senior returns. Life is alright. I find the want of change of clothing a distinct drawback. An occasional box of good Egyptian cigarettes or a nice light pipe, or one or two khaki handkerchiefs or a toothbrush would be most acceptable. Although my toilet is pretty spasmodic. I hear Bulgaria and Romania are coming in. This is good.

Best luck, Cuthbert

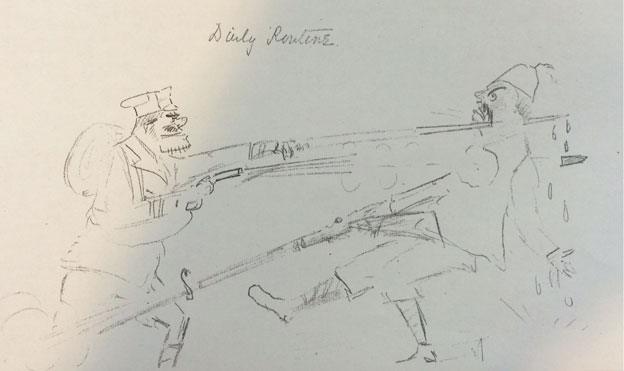

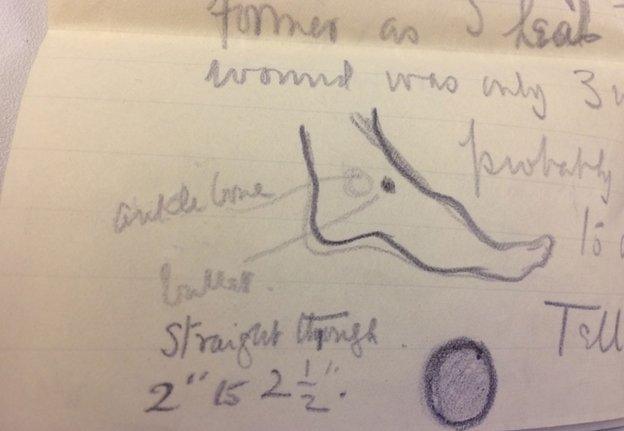

Cuthbert was fond of drawing little sketches on his letters. In one - in what might seem now a little like the 1915 equivalent of a selfie - he depicts himself bayonetting a Turkish soldier, and captions the picture: "Daily Routine." In another he draws a picture of the injury to his ankle by a piece of shrapnel and writes: "Straight through 2' to 2½'".

Lord Ashcroft, who had bought three of the six Fusiliers Victoria Crosses and displayed them in his extensive collection at the Imperial War Museum, agreed to temporarily lend the medals to the Fusiliers Museum after being approached personally by Col Gorski.

As well as being a prominent donor to the Conservative party and prolific political pollster, he also has a fascination with military history and, in particular, with the concept of heroism during warfare.

"The 'six before breakfast' was an action of collective bravery," he says. To put it into context, he said, the Lancashire Fusiliers had started the day with 27 officers and 1,002 other men, and 24 hours later a headcount revealed just 16 officers and 304 men.

Capt Richard Raymond Willis, Sgt Frank Edward Stubbs, Sgt Alfred Richards

Capt Richard Raymond Willis, 1876 - 1966 Willis was in charge of "C" Company at Gallipoli and it was from his Company that four of the six VCs came. As the boats approached the beach the slaughter began and Willis stood up in full view of the enemy to calm his men, famously holding his cane aloft and shouting the battle cry, "Come on Boys, Remember Minden". He died in a nursing home in Cheltenham in 1966, aged 89, having sold his VC due to financial difficulties.

Sgt Frank Edward Stubbs, 1888 - 1915 Awarded the VC for action during the landings at W Beach. His task on landing at Gallipoli was to lead his platoon up the south side of hill 114 to the tree on top of the hill, where he was to join up with D company. He led his men through the heaviest fighting and, though his platoon successfully reached its target, Stubbs fell just yards short of the solitary tree, receiving a bullet to the head which killed him instantly. He was the only one of the VC winners to die on the day of the landings.

Sgt Alfred Richards, 1879 - 1953 On reaching W beach he was shot so many times that his leg was almost severed. Constant movement was the only course of action and he crawled over the barbed wire to relative safety where ignoring his own injuries he continued to encourage others. He was evacuated to Egypt where his leg was amputated. He served in the Home Guard in WW2 and died in London in 1953.

This week, I watched alongside delighted staff at the Fusiliers Museum, as the culmination of three years hard work came together with the arrival of the three Ashcroft VCs, to join the Bromley medal and the other two VCs.

The medals arrived on Monday under tight security in a large wooden box. Each is worth well over six figures.

For the first time all six VCs are in the same place, at the same time, just in time for the 100th anniversary celebrations.

"I'm feeling so emotional - I might cry," says Stevenson as she checks through the medals before placing them in alarmed glass display cases.

"It's quite moving when you realise what they did to deserve these medals, and here they all are on their 100th anniversary. It's a very special moment."

The next day 21 members of the family of John Grimshaw, one of the Victoria Cross holders, came to the museum to see the medals in place.

"It's the first time I've seen them all together," says 72-year-old Edna Aspinall, who is John Grimshaw's niece. "I tell all my children and grandchildren about it. It's something that makes us so proud."

John Grimshaw died in 1980, aged 87.

She continues: "I remember as a child Uncle John coming to visit and my mother telling us to take the milk bottle off the table. We all had to smarten up whenever he visited. To us, he was a hero - but he was our hero."

Medals awarded to Cpl John Elisha Grimshaw

On Saturday 25 April there will be a special concert by the Royal Marines Band, with a newly commissioned piece of music, and a march through Bury to commemorate the anniversary

The medals will stay together on display at the Fusiliers Museum until 17 May

What was Gallipoli?

Australian soldiers use periscopes to locate snipers

The Allies and Germany had reached a stalemate on the Western Front just months into World War One

Britain and France thought they could help Russia on the Eastern Front by defeating Germany's Turkish allies - the Ottoman Empire

After a failed naval attack, the Allies tried to capture Constantinople (now Istanbul) via the Gallipoli Peninsula by land assault

British, French and their dominions', Canadian, Indian, Australian and New Zealander troops took part

They faced months of shelling, sniper fire and dysentery before abandoning the campaign

45,000 Allied troops died for no material gain. although the Turkish Army was tied down for eight months

86,000 Turkish troops died. Commander Mustafa Kemal survived and went on to found modern Turkey

Andrew Bomford's report will feature on Radio Four's PM Programme at 17:00 BST on Thursday 23 April

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.