'They hate black people'

- Published

Portugal is often praised for its success in integrating immigrants but in the suburbs of Lisbon police are being accused of racism and brutality.

Jailza Sousa's young son is afraid when she hangs out the washing on their first-floor balcony.

"He's traumatised," says the 29-year-old from Cape Verde. "He says, 'Don't go there because you're going to get shot.'"

Looking down the narrow, potholed streets, she remembers what happened one day in February, earlier this year.

It was noon in Cova da Moura - a ramshackle suburb on a hill on the outskirts of Lisbon built by immigrants from Portugal's former African colonies.

The restaurants serve cachupa, a slow-cooked stew of corn, beans and meat which is the national dish of Cape Verde. The streets resonate to the sounds of music from Angola.

It's a colourful, friendly place by day, but it has a reputation for drugs, crime and violence. It's a place that taxi drivers refuse to go at night.

On 5 February, a team of police officers had a young man called Bruno up against a wall. They were searching him and started beating him - his blood stained the wall and street for several days afterwards. Bystanders started protesting, and the police reacted with shotguns loaded with rubber buckshot.

Jailza Sousa on her balcony

"A policeman came walking in this direction, and he pointed a gun," says Sousa. She had just hung out her washing, and was mopping the floor.

"He shot me in the chest, then when I was trying not to fall, he cocked his gun and hit me again in the hip.

"He saw me trying to recover my balance, if it had been by chance he wouldn't have shot the second time - and he did."

"They treat us like animals," Sousa says of the police. "It's a black neighbourhood - they treat us like we're all here to be exterminated."

Sousa was taken to hospital while two people who work for a local human rights organisation, Moinho de Juventude, or Mill of Youth, set off for the police station to find out what had happened to Bruno.

Bruno after he was released

The two men, Flavio Almada and Celso Lopes, were accompanied by about five other young men who had witnessed the incident.

When they arrived at the police station, they say three police officers were blocking the entrance.

"Suddenly about 15 or 20 cops came with sticks, with shotguns, and started trying to kick and punch us, trying to hit us with batons," says Lopes.

"And I said 'OK, I'm leaving,'" claims Almada. But he says one police officer cocked his shotgun. "And quickly, he shoot."

Lopes was hit in the leg by rubber buckshot. He, Almada and three others were then taken inside the police station, where they were handcuffed. They allege the beatings continued accompanied by extreme racist abuse.

Lopes's leg after he was treated in hospital

Almada says one officer told him, "You don't know how much I hate you. If I had the power, you would all be exterminated."

He says he was terrified. "I will never forget his face. I will never forget his words."

The men claim other police officers told them they should join Islamic State.

Lopes says for five hours they received no medical attention. Eventually all five men were admitted to hospital.

Almada says he suffers from terrible nightmares and some of the injuries have still not healed. When he smiles he reveals a chipped front tooth.

Four separate investigations are underway into what happened. Both the Interior Ministry and Portugal's racial discrimination commission are investigating the conduct of the police.

Almada, Lopes and their friends face charges of invading the police station, and they in turn are pressing their own charges of torture and racism against the police.

"When the police come the police are the law," says Lopes. "You are no longer living in a democracy, you are living in a police state."

The BBC requested an interview with the police to discuss the incident and relations with communities such as Cova da Moura, but the police declined.

At the time, the media reported that Bruno had thrown a rock at a police van, breaking a window and injuring an officer. Bruno and eyewitnesses deny this.

Bruno says he was singled out by the police

It was also reported that the men had tried to storm the police station and that the five who were detained had suffered "minor" injuries after resisting arrest. There were later reports that a police officer was taken to hospital with a broken arm.

This incident re-ignited long standing claims of police brutality and racism - a story told in the graffiti on Cova da Moura's walls.

A video circulating on social media, external shows another recent police raid in Cova da Moura which was filmed by a resident. In the early hours of the morning, police with shotguns and wearing balaclavas can be seen walking through the streets, and shots can be heard.

It's claimed a young man was hit in the head by rubber buckshot.

These police are part of what's known as a Rapid Intervention Team - highly trained and heavily equipped, and normally only called in when a situation escalates beyond what the regular police can handle. But Almada says they are a common sight.

He introduces me to Whassysa Magalhaes, a teacher and part of the management of Moinho de Juventude. One day the police stopped her and asked for her ID.

"I was late and said I had to go to university and they said, 'Black people study?'" she recalls, adding that they used a derogatory term for black people.

Others tell stories of being called monkeys or having their ID cards destroyed by police.

"Here, police just ask you to stop and if you don't stop or you ignore them, they shoot at you, start kicking you, hitting you with sticks," says one young man, Fabio.

"They hate black people."

In another part of Lisbon, Quinta da Lage, the side of one house is painted with a mural of a young black man, and the words "RIP Kuku, let justice be done."

The house belongs to Domingas Sanches. In 2009, her 14-year-old son Elson, also known as Kuku, was driving with friends in a stolen car when they were stopped by police. They started to run away, but Elson was caught by one of the officers. He managed to break away, and was then shot in the head at point blank range by the policeman.

"It's difficult but life goes on, sometimes I cry, I miss him," says Sanches.

The policeman was tried for gross negligent manslaughter and acquitted after claiming he heard a sound like a pistol being cocked, and saw a metallic object in Elson's hand. A weapon was recovered at the scene, although Elson's defenders say it had no fingerprints on it and claim it was planted.

"I felt a great disgust," says Sanches. "If it were a 14-year-old kid killing a policeman, then someone would be found responsible."

"The only thing I wanted was that justice be done, but it probably won't be."

This sense of injustice is widespread. Activists claim that 14 young black men have been killed by police since 2001, and that no police officers have been held responsible for those deaths, though the numbers include some deaths where police responsibility is disputed.

One person who remembers the first of those shootings is Lieve Meersschaert. Born in Belgium she came to Cova da Moura in the early 80s where she co-founded Moinho de Juventude, the organisation that Almada and Lopes work for.

In 2001 a police officer killed a man by shooting him in the back, she says, prompting an escalation of violence.

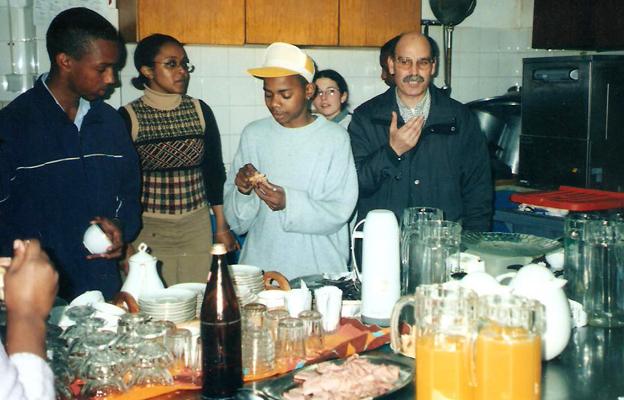

Eventually Moinho arranged a dinner for local police commanders to meet young people from the neighbourhood - including the sister of the man who was shot.

"It was very funny when the 35 police station commanders arrived, they didn't want to come in. And afterwards we almost had to kick them out, because they didn't want to leave," she says.

Guests at the dinner with local police commander, Antonio Manuel Pereira, on the right

She points to a photo. "This is at the end of the dinner. We have the godmother of the boy who was killed kissing on the cheek the police commander."

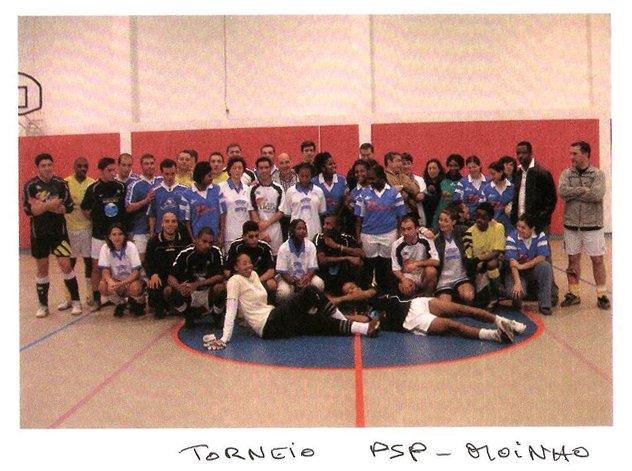

After that meeting the police commander of the local area, Antonio Manuel Pereira, worked on improving relations between police and residents. They held football tournaments and children spent time with the officers.

But Pereira retired in 2012 and his replacement put less emphasis on community policing, says Meersschaert. Around the same time a pilot programme called the Critical Neighbourhoods Initiative, which promoted closer co-operation between police and residents, was cancelled by the newly elected conservative government.

Meersschaert says brutality has got worse since then, and that the government ignored warnings.

The BBC made several requests for interviews to the Interior Ministry and the Prime Minister's office, which were all turned down. Eventually the Ministry provided a statement about the police, referred to here as the PSP.

"We reject the suggestion of the existence of police violence and racism. Community policing was, and will continue to be the basis for the deployment of police resources, with a view to ensuring the safety of people and property and to prevent crime. [Community policing] has never been abandoned by the PSP, either in Cova da Moura or in any sensitive urban area. On the contrary, the PSP carries out, on average, more than 15,000 community or neighbourhood policing operations a year, and in sensitive urban areas, interventions of this nature have been increasing. It is not correct to establish a correlation between the reduction of police officers in recent years and purely economic measures."

Almada feels that the problems in Cova da Moura come from a deeper attitude in Portuguese society.

"Racism is beyond the police, it's the whole frame of society, it's a big issue and I don't believe they want to change all these things," he says. "If you see Portugal receiving a prize for well integrated immigrants it's a big lie."

But Portugal's High Commissioner for Migration, Pedro Calado disagrees. "We don't have this big problem of racism in our society," he says.

Calado - the head of the government body tasked with promoting integration, and dealing with racial discrimination - points to the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX). This global study ranks countries according to how successfully they integrate migrants. Portugal currently comes second, behind Sweden.

Portugal's defenders also point out that it hasn't had riots like London or Paris, and that there's little anti-immigrant political rhetoric in Portugal.

"I have this clear perception that what happened in Cova da Moura is not the general situation of the country. This was an exception," says Calado.

He also oversees Portugal's Commission for Equality and Against Racial Discrimination, which handles racial discrimination complaints.

"We don't have many complaints," he says as he shows me a report containing the data. It indicates that from 2005-13, there were 75 complaints against the security forces.

I ask how many of those complaints were upheld.

"We would have to look at the data," says Calado. "I cannot tell."

'Another world is possible' says the writing on the Moinho da Juventude building

Despite several weeks of emailing back and forth after our interview, the High Commission wouldn't tell me the number of complaints upheld against the security forces for racial discrimination. They say they lack the resources to process the data.

But piecing together the data that is available, it seems that fewer than 10 racism complaints against the security forces have been upheld in the past 10 years in the whole of Portugal. In places such as Cova da Moura, this is seen as evidence of a broken system which doesn't hold police accountable.

Although Portuguese officials deny a deep, systemic problem with the police, the recent incident involving Almada and Lopes has led to some changes.

The Interior Ministry met people from neighbourhood organisations, including Moinho de Juventude and promised to set up a new Early Warning Commission to avoid conflict.

Almada says he hopes that what happened to him might make a small difference, but he's cautious.

"I want to see the results," he says. "I'm like that guy the disciple of Jesus, I just want to see."

'Police State' Portugal is broadcast on Crossing Continents on Thursday 23 April at 11:00 BST on BBC Radio 4. It is on Assignment on BBC World Service on the same day.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.