A Point of View: Why don't Americans mark their Civil War like the British do WW2?

- Published

The 150th anniversary of the end of the American Civil War passed with fairly low-key commemorations, says historian David Cannadine. Why are similar events in the UK such a big deal?

Earlier this month, the United States marked the 150th anniversary of the conclusion of the American Civil War. It had lasted for four years, and had claimed the lives of more than 700,000 troops, but in the end, the north triumphed over the south, the Union was saved, and the slaves were freed. By early 1865, it had become clear that the south couldn't win, because it lacked the military and material resources that it needed to keep on fighting, and on 9 April, the Confederate Gen Robert E Lee surrendered his army to the Union Gen and future President Ulysses S Grant at Appomattox Court House in the state of Virginia. In fact, this dramatic encounter between the two pre-eminent military commanders in the conflict didn't result in the immediate cessation of all hostilities.

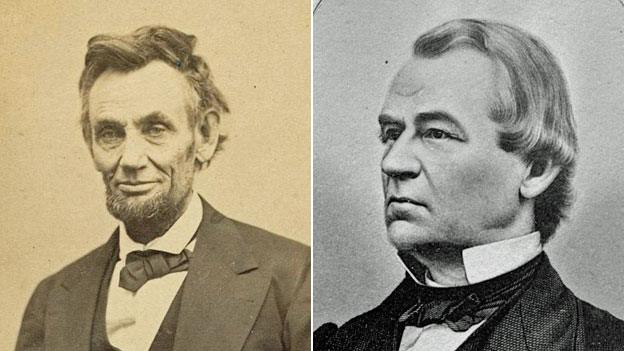

The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln a few days later led some to hope that the south would fight on, the remaining Confederate armies didn't surrender until the early summer, and it was only in August 1865 that Lincoln's successor, President Andrew Johnson, formally proclaimed the war to be ended, and that "peace, order, tranquillity and civil authority now exists in and throughout the whole of the United States of America".

Nevertheless, if there is one date that more than any other signified that the American Civil War was effectively over, it was indeed 9 April 1865, and the 150th anniversary of that closure has been widely observed in many parts of the United States. Lee's surrender at Appomattox was re-staged by actors playing the parts of the two generals, who were appropriately dressed in period costume.

At Arlington National Cemetery a brass band wearing Civil War uniforms played Yankee Doodle and Dixie, two of the most famous songs from the time, bells were rung in many parts of the country for four minutes, one for each year of the conflict, on battlefields, at museums and in history classrooms, many Americans pondered the continuing significance of the Civil War and its legacy, and wondered whether the cessation of hostilities really did bring about the restoration of "peace, order and tranquillity", as President Johnson had claimed.

An actor plays the role of Confederate General Robert E Lee

Abraham Lincoln was succeeded as president by Andrew Johnson

Yet these American anniversary observances seemed very localised and understated compared with how we do such things in Britain, where we are more concerned with making as much as we can of as many commemorations as possible. And this contrasted approach to the recollection of historic events will soon be vividly demonstrated, when the United Kingdom will mark the 70th anniversary of VE Day, and thus of the end of World War Two in Europe, in a series of observances, beginning on Friday 8 May, which will continue over the weekend.

There will be a service of remembrance in St Paul's Cathedral and a service of thanksgiving at Westminster Abbey. Schools across the country are being encouraged to mark and to discuss VE Day, bonfires will be lit from Cornwall to Northumberland, church bells will be rung, and a two-minute silence will be observed. There will be street parties in many cities, towns and villages, a rock concert will take place in Horse Guards Parade, veterans will process along Whitehall, and there will be an RAF fly-past including fighters and bombers from WW2.

By extraordinary coincidence, these commemorative events, combining as they will centralised state sponsorship with many local initiatives, will take place immediately after the general election on Thursday 7 May. This in turn means there's likely to be a very sudden and dramatic shift in the national mood - from bitter political divisions about where Britain is headed and who should take it wherever that might be, to a nostalgic remembrance, and perhaps an envious appreciation, of the very different feelings of unity, gratitude and patriotic pride that many people shared seventy years ago. It's also quite possible that across all those three days in the aftermath of the election, Britain will have no government and no prime minister, because if there is an inconclusive outcome, as seems highly likely, the politicians and party leaders will be busy negotiating another coalition - even as the bonfires are lit, the church bells ring and the planes fly overhead.

But while the political horse-trading may detract from the VE Day commemorations, it seems likely that they will far outstrip those observances recently put on by the Americans to mark the end of the Civil War, and there are some good specific reasons why this should be so. A century and a half on, the American Civil War is not memory but history, and so there is no vivid or immediate personal connection with it. But 70 years on, WW2 is still - just - memory as well as history, and 2015 may be the last time when there will be significant numbers of surviving veterans still able to participate.

It's also important to remember that whereas the Civil War divided the United States, and left the losers alienated and disenchanted in ways that have still not completely healed, the WW2 united most people of Britain in the face of Nazi tyranny and aggression, and they all ended up on the winning side. And so it is much easier for us to celebrate the triumphant anniversary of 1945, wholeheartedly and unequivocally, than it is for the Americans to celebrate the much more ambiguous anniversary of 1865.

What was the American Civil War?

Abraham Lincoln's election as president in 1860 triggered seven southern states to declare their secession and form the Confederate States of America, but Lincoln's administration refused to recognise it as legitimate

The root causes of the war are still debated - but differences over slavery between the northern and southern states were a crucial element

Lincoln had pledged to keep slavery out of newly formed western territories, but the Confederates did not believe in the power of the national government to prohibit it

In the first battle, the Confederates bombarded Union soldiers at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on 12 April 1861

After several years of fighting, the Northern army was victorious and the rebellious states returned to the Union

But aside from these particular contrasts, there are also more general reasons why the Americans are less invested than the British are in the contemporary cult of commemoration. One reason we are so eager to celebrate the anniversaries of past events in this country may be that they often remind us of an earlier time when Britain counted for much more in the affairs of the world than it does now. And this applies especially to the many commemorations of WW2, for that was arguably the last time this nation played a starring and heroic part on the stage of world history. The United States, by contrast, has been making history just about every year since 1945, sometimes for good, sometimes for ill - but this also means it is much more engaged with the global present and future than Britain is, and that America has less reason than we do to seek comfort by constantly dwelling on those earlier times of national greatness that have long since disappeared.

It's also easier for Britain, which is a relatively small and unified nation, with a strong central government, to stage nationally-inclusive displays of commemoration than it is for the United States, which is a country with a relatively weak federal government, that many people dislike and distrust, and which oversees a vast transcontinental empire extending from one ocean to another and beyond. Despite devolution and the Scottish referendum, it should still be possible for the inhabitants of Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland to join England in celebrating the anniversary of 1945, because all three nations boast strong military traditions, and many Ulstermen, Welshmen and Scotsmen served alongside Englishmen during WW2. By contrast, certain parts of the United States were completely unaffected by the Civil War, and neither Alaska, nor Hawaii nor Puerto Rico were at that time governed from Washington - Alaska belonged to Russia, Hawaii was an independent kingdom, and Puerto Rico was a Spanish colony, which means that the American Civil War is not part of their history at all.

It's also the case that the United Kingdom has a great deal more history to commemorate than does the United States. Although this has become an increasingly controversial view in recent decades, for many people the history of America only goes back as far as 1492, when Columbus allegedly "discovered" it, or to 1607, when the first successful British settlement was established at Jamestown. But in addition to celebrating the end of WW2 this year, we in Britain are also marking the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta and 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt. Against such venerable commemorations, the 50th anniversary of the release of the film version of The Sound of Music, which took place in America in March 1965, doesn't seem to count for all that much.

A Point of View is broadcast on Fridays on Radio 4 at 20:50 BST and repeated Sundays 08:50 BST or listen on BBC iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.