The moment Nepal's earthquake hit my home

- Published

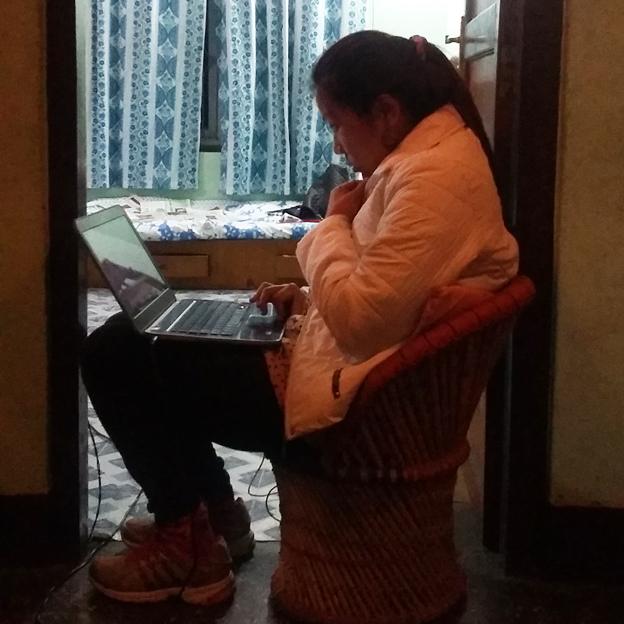

People from Bhrikuti Rai's neighbourhood waiting for news

More than 4,000 people died in the huge earthquake that hit Nepal at the weekend, and nearly 8,000 have been injured. Millions more have had their lives turned upside down - including journalist Bhrikuti Rai who was at her home in Kathmandu when it happened.

At exactly 11:58 on Saturday morning, my brother abruptly stopped his clumsy dance to OT Genasis's song Coco and screamed "bhuichaalo" or earthquake.

As he moved towards the door, the mirror in my room shook violently. "Stay there," he said calmly as I clutched a black tote bag to my chest, feeling my breath getting shorter and shorter. I think I screamed and then yelled while he reminded me not to move from the doorway - we've always been taught it's one of the safest places in a building during an earthquake. This was the big one we had all dreaded for years.

My voice was drowned out by the rattling of my laptop on the desk, the mirror screeching against the wall, the yelling of my neighbours downstairs and the doors and windows violently slamming back and forth.

And then, after what seemed like an eternity, it stopped, or maybe it didn't. We looked at each other and put on our shoes rather calmly. In the next few seconds, before we left our flat, I managed to shove my laptop, purse and passport, yes my passport, in my already overflowing tote. I looked back at my room - I had just cleaned it that morning - grabbed my old camera bag, slung it over my shoulder and hurried down the stairs.

But before I could turn towards the main door, I saw a section of the wall that surrounds our building collapse.

We rushed down the stairs and jumped over the rubble to find all our neighbours gathered in the narrow alley outside.

We made our way to the yard of a nearby block where people were huddled together, some holding young babies, some in shock. Women were screaming from the fourth floor and men were trying to take their bikes to safer places.

Our feet crushed the plants in the small kitchen garden into the muddy ground as the tremors kept coming.

This wasn't a very safe spot, so we walked further along the narrow alley, petrified as we scanned the rubble and the cracks in the concrete walls. More than a dozen people stood there looking at the tangled electric wires and bent electricity poles.

And then, just as the earth beneath us jolted once again, more people rushed out of their homes, barefoot. None of my coaxing to slip on a pair of shoes helped.

As we walked towards the only open space in our neighbourhood, a school playground, I took a dozen photographs with my trembling hands. Seeing so many people huddled there, some running back to their homes to get blankets, chairs and masks to fight the dust and cold sent a chill down my spine. This was really happening.

People were frantically trying to call their loved ones, cursing the network and the intermittent connections. There were kind souls who offered to carry the injured and bring water for the rest of us. Some with smartphones and better internet connections shared horrifying pictures of buildings and roads razed by the earthquake.

Our tall Dharhara - a 203ft tower built in 1832 which was rebuilt after the big earthquake of 1934 - had collapsed, as had several other old temples and palaces.

"I feel like a refugee," said my sister, who lives downstairs and had joined us at the school playground. Another man joked about how we all looked like badi pidit or flood victims. None of which was funny.

Suddenly all the headlines of the stories I had written, external and read warning of a looming earthquake flashed before my eyes. What we had dreaded for years but only discussed on Earthquake Safety Days and the anniversary of the great quake of 1934 was unfolding in front of us. This day, 25 April 2015, would be the dark day our generation would talk about for the rest of our lives, like my grandparents did about 1934.

By about 5pm there had been a dozen or more aftershocks - people calmly walked back and forth to their homes bringing essential supplies - water, top up cards for their phones, noodles, mats and blankets.

I went back home too, to find my books and belongings scattered across the floor.

The television was lying on the ground but thankfully it had no cracks. I transferred everything from my tote to a backpack, picked up a yoga mat, umbrella, and a large bottle of water and headed back to the school playground.

As the night set in, more people joined us - almost 300 of them. There were rumours circulating that there would be another major jolt. Afraid that their homes could collapse, they had nowhere else to go. Some played cards under the flickering light of their mobile phones while others snored under the night sky.

As a result of filing stories, contacting the Ministry of Home Affairs and checking updates, my laptop battery was almost exhausted. And so was my back. Luckily the power was back on in our neighbourhood, so after eight hours my brother and I headed home. After dozens of aftershocks we were sure we could withstand a few more and decided not to camp out that night after all.

Almost twelve hours after the earthquake hit, the two of us were once again seated in the same doorways looking at each other every time another tremor shook the windows. "Not a big one," we said and got back to our computer screens. He tried to find out as much as he could about tectonic plates while I kept an eye on the news, pausing once in a while to see if the shaking I could feel was another tremor or just my legs trembling.

My sisters and neighbours called to check if we were really staying at home for the night. I looked at my brother again and we decided to take turns sleeping instead of freezing outside. Moments later, just when he had started snoring, the windows rattled violently yet again. He peeked from the door, signalling that it was his turn to stay up.

That night I slept in my shoes with the lights on. I was woken up by two more strong aftershocks.

Although my neighbourhood hadn't suffered much physical damage, I saw the fear on people's faces - they had gathered in every open space, on pavements and on river beds.

On Sunday, I went to see what was happening at the airport and offered to share cab with a young boy who was desperately looking for a taxi to take his ailing grandmother to hospital. She had injured her back while trying to run from her house.

I am relieved to say that none of my friends or relatives was injured.

The airport was chaotic with people hurrying to leave the country. Taxi drivers and hotel agents bargained with the sleep-deprived tourists.

As I drove around town, I saw more people in temporary shelters. With few vehicles on the streets, Kathmandu looked like a vast city of tents. The neighbourhoods where buildings were cracked and reduced to mounds of brick and splintered wood were deserted.

It was only then that I realised the water jars in my flat were empty and I wondered whether I had enough food in the cupboards. As I made my way back home that night along the deserted alleys of Baneshwor, I thought of thousands of others who would spend another dark, uncertain night in the open and wondered how long it will be before life returns to normal.

I have stocked up on food and water - I have enough to last a week - but when I walk past the rubble, closed petrol stations, and shops I am reminded how difficult the weeks ahead are going to be.

You can follow @bbhrikuti, external on Twitter and on her blog, external.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.