The birth of the weather forecast

- Published

FitzRoy's weather forecasts were taken up by Derby race-goers

The man who invented the weather forecast in the 1860s faced scepticism and even mockery. But science was on his side, writes Peter Moore.

One hundred and fifty years ago Admiral Robert FitzRoy, the celebrated sailor and founder of the Met Office, took his own life. One newspaper reported the news of his death as a "sudden and shocking catastrophe".

Today FitzRoy is chiefly remembered as Charles Darwin's taciturn captain on HMS Beagle, during the famous circumnavigation in the 1830s. But in his lifetime FitzRoy found celebrity not from his time at sea but from his pioneering daily weather predictions, which he called by a new name of his own invention - "forecasts".

There was no such thing as a weather forecast in 1854 when FitzRoy established what would later be called the Met Office. Instead the Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade was founded as a chart depot, intended to reduce sailing times with better wind charts.

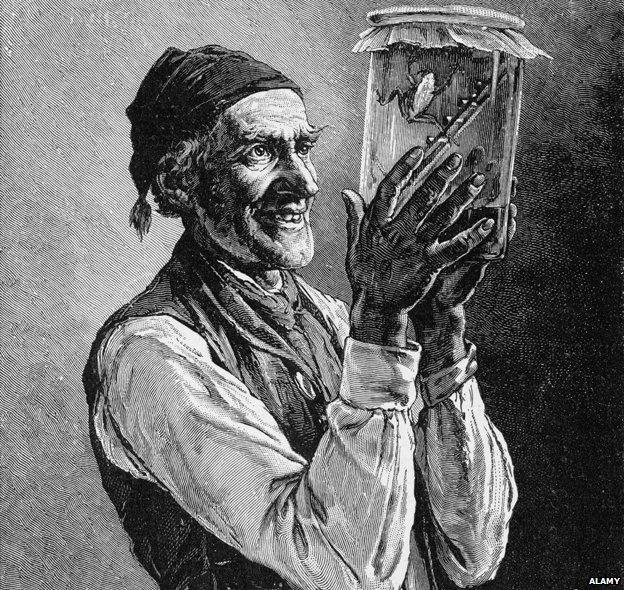

With no forecasts, fishermen, farmers and others who worked in the open had to rely on weather wisdom - the appearance of clouds or the behaviour of animals - to tell them what was coming. This was an odd scenario - that a bull in a farmer's field, a frog in a jar or a swallow in a hedge-row could detect a coming storm before a man of science in his laboratory was an affront to Victorian notions of rational progress.

Early weather prediction, using frogs

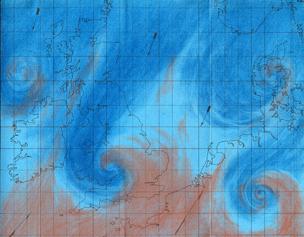

Yet the early 19th Century had seen several important theoretical advances. Among them was an understanding of how storms functioned, with winds whirling in an anticlockwise direction around a point of low pressure.

Weather charts, another innovation, made it easier to visualise the atmosphere in motion. One influential theory argued that storms occurred along unstable fault lines between hot and cold air masses, just as we know earthquakes today happen on the boundaries of tectonic plates.

But despite this, the belief persisted among many that weather was completely chaotic. When one MP suggested in the Commons in 1854 that recent advances in scientific theory might soon allow them to know the weather in London "twenty-four hours beforehand", the House roared with laughter.

But FitzRoy was troubled by the massive loss of life at sea around the coasts of Victorian Britain. Between 1855 and 1860, 7,402 ships were wrecked off the coasts with a total of 7,201 lost lives. FitzRoy believed that with forewarning, many of these could have been saved.

After the disastrous sinking of the Royal Charter gold ship off Anglesey in 1859 he was given the authority to start issuing storm warnings.

FitzRoy was able to do this using the electric telegraph, a bewildering new technology that, the Daily News observed, "far outstrips the swiftest tempest in celerity".

With the telegraph network expanding quickly, FitzRoy was able to start gathering real-time weather data from the coasts at his London office. If he thought a storm was imminent, he could telegraph a port where a drum was raised in the harbour. It was, he said, "a race to warn the outpost before the gale reaches them".

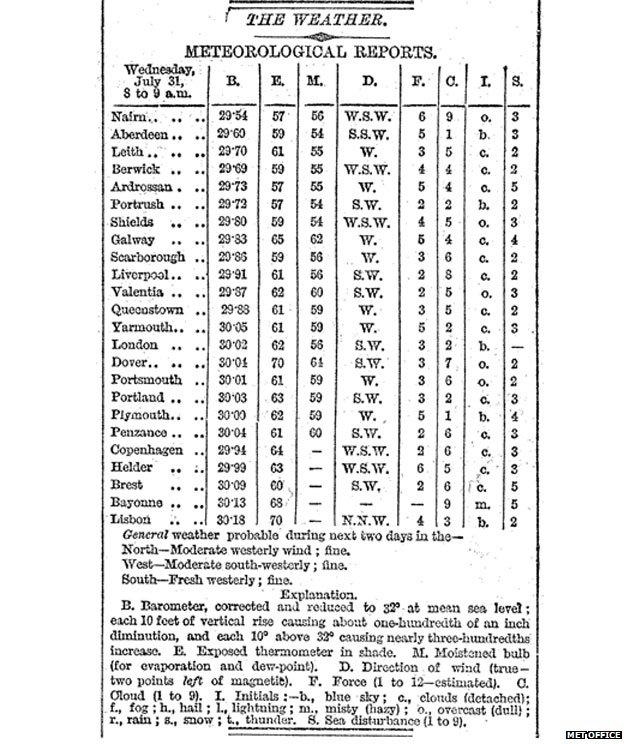

The Times weather forecast for 1 August 1861

The temperature in London was to be 62F (16.7C), clear with a south-westerly wind

The temperature in Liverpool was to be 61F, very cloudy with a light south-westerly wind

It was to be overcast in Nairn,Portsmouth and Dover with the latter predicted to hit a pleasant 70F, the same as Lisbon

The forecast also covered Copenhagen, Helder, Brest and Bayonne

FitzRoy's storm warnings began in 1860 and his general forecasts followed the next year - stating the probable weather for two days ahead.

For FitzRoy the forecasts were a by-product of his storm warnings. As he was analysing atmospheric data anyway, he reasoned that he might as well forward his conclusions - fine, fair, rainy or stormy - on to the newspapers for publication. "Prophecies and predictions they are not," he wrote, "the term forecast is strictly applicable to such an opinion as is the result of scientific combination and calculation."

For years the public had read quack weather prognostications in almanacs, but this was the first time that predictions had been sanctioned by government. First published in The Times in 1861 and syndicated in titles across Britain, they soon became fantastically popular.

Following a particularly successful forecast, satirical magazine Punch anointed FitzRoy their new "Clerk of the Weather" and suggested he should henceforth be known as "The First Admiral of the Blew".

The forecasts soon became a quirk of this brave new Victorian society. Their appeal instantly stretched beyond just fishermen and sailors. Organisers of country fairs, fetes and flower shows obsessed over them. They had a particular appeal for the horseracing classes who used the predictions to help them pick their outfits or lay their bets.

But calculated by hand on threadbare data, the forecasts were often awry. In April 1862 the newspapers reported: "Admiral FitzRoy's weather prophecies in the Times have been creating considerable amusement during these recent April days, as a set off to the drenchings we've had to endure. April has been playing with him roughly, to show that she at least can flout the calculations of science, whatever the other months might do."

Reporting on the biggest date in the sporting calendar, the Derby, a month later, The Age wrote: "With what eagerness in every quarter was the meteorological column consulted in the newspapers where Admiral FitzRoy records the forecast of the weather, and with what satisfaction did the experienced interpreters of the prediction see that he had set down for the south of England - 'Wind SSW to WNW moderate to fresh, some showers', which of course indicated that it would be a remarkably fine day, and that the umbrellas might be left behind."

FitzRoy's hand-drawn weather chart

But often FitzRoy was surprisingly accurate and when he was mistaken he replied to his critics - "those whose hats have been spoilt from umbrellas being omitted" - through the letter pages of the Times.

This willingness to engage increased his popularity and solidified his reputation as a daring and gallant scientist. Over the next years a prize racehorse was named in his honour, as was a ship, and on one occasion Queen Victoria sent her messengers to his house to find out if the weather was going to be calm for her crossing to Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

Some papers suggested commercial uses for the forecasts. When French tightrope walker Charles Blondin arrived in London, proposing to traverse a wire over the Crystal Palace, Punch urged the organisers to charge extra for tickets in bad weather.

"The circumstance of a windy day must add very much to the excitement which is occasioned by Mr Blondin's terrific ascent. Admiral FitzRoy's 'forecasts' in the Times would generally enable them to anticipate the day before. When he is dancing on the tight-rope in a tempest, his spectators should give the space under his rope a wide berth."

But for all the light-hearted quips, FitzRoy faced more serious difficulties. Some politicians complained about the cost of the telegraphing back and forth. The scientific community were sceptical of his methods. While the majority of fishermen were supportive, others begrudged a day's lost catch to a mistaken signal.

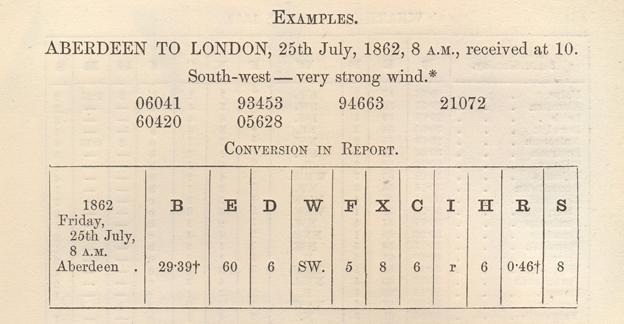

The signals

B - Barometer

E - Exposed thermometer in shade

D - Difference of wet bulb

W - Wind direction

F - Force (on Admiral Beaufort's Scale)

X - Extreme force since last report

C - Cloud (1-9)

I - Type of weather (b - blue sky; r - rain etc)

H - Hours of rainfall

S - Sea disturbance

A typical complaint was filed in the Cork Examiner. "Yesterday, at two o'clock, we received by telegraph Admiral FitzRoy's signal of a southerly gale. The gallant meteorologist might have sent it by post, as the gale had commenced the day before and concluded fully twelve hours before the receipt of the warning."

To compensate, FitzRoy worked harder than ever to decode the British weather. He published a book and gave lectures, but by 1865, with his critics in full voice, he was exhausted and beset by the return of an old depressive condition.

He retired from his west London home to Norwood, south of the capital, for a period of rest but he struggled to recover. The last forecast of his lifetime was published in his absence on 29 April 1865. It predicted thunder storms over London.

FitzRoy's legacy explained

The following morning FitzRoy got out of bed to get ready for church. He kissed his daughter as he walked to his dressing room. Then he turned the key in the lock, and killed himself.

At the time it seemed that FitzRoy's forecasting project had ended in failure. But today his vision of a public forecasting service, funded by government for the benefit of all, is fundamental to our way of life.

His department, which began with a staff of three, now employs more than 1,500 people and has an annual budget of more than £80m. Perhaps the most fitting tribute came in 2002 when one of the BBC's iconic shipping forecast regions was renamed from Finisterre to FitzRoy in his honour.

Dame Julia Slingo, the Met Office's current chief scientist explains: "FitzRoy was really ahead of his time. He was not mistaken or eccentric, he was just at the start of a very long journey, one that continues today in the Met Office."

Peter Moore is the author of The Weather Experiment

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.