VE Day: The last British Dambuster

- Published

As VE Day - the end of World War Two in Europe - is marked, the last British survivor of the famous Dambusters raid explains what it was like to take part.

"I feel privileged and honoured to have taken part," says George "Johnny" Johnson. "It's what we were there for. We were determined to do our bit."

Johnson, now aged 93, is the last British survivor of the original Dambusters, the Royal Air Force's 617 Squadron, who conducted a night of raids on German dams in 1943 in an effort to disable Hitler's industrial heartland.

Their exploits were legendary even before being made into a film, The Dam Busters, released in 1955. A scene showing back-spinning cylindrical bombs, designed by engineer Barnes Wallis, bouncing along the water to avoid protective nets before sinking and breaching the dams with their explosive power, is one of the most famous in British film history. The Dam Busters March is still played at military events.

But Johnson isn't entirely happy with the film's depiction of the operation, codenamed "Chastise", external, on that night of 16-17 May. "The thing that was disappointing from our point of view was that the raid carried out by my crew, on the Sorpe dam, wasn't mentioned," he says.

A "bouncing bomb" falls away from an Avro Lancaster during the tests

The Dambusters, led by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, formed shortly before the mission amid the strictest secrecy. They breached two dams, on the Mohne and the Eder, using the bouncing bombs, leading to enormous flooding in the Ruhr valley. Estimates of the civilian death toll vary between 1,200 and 1,600.

The raid involving Sgt Johnson's crew did not allow the use of the same technology. The Sorpe dam was differently constructed, so it needed a direct strike from above using a conventional bomb. Johnson had the role of lining up the best point from which to drop.

His Lancaster bomber, piloted by Joe McCarthy, an American serving in the Canadian Air Force, was late leaving. The intended plane developed a hydraulic leak shortly before take-off from RAF Scampton, in Lincolnshire. A replacement, lacking some of the usual navigation equipment, was used instead.

The Lancaster Bomber

The Lancaster was one of the most dangerous places to be in World War Two - the life expectancy of a new recruit was just two weeks

Lancaster crews took part in 156,000 missions and dropped 618,378 tons of bombs on targets in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe

On 16 and 17 May 1943, the Dambusters - a squadron of 19 Lancasters - attacked dams across Germany. The mission became legendary and was a great boost to British morale

The crew approached the Sorpe dam about half an hour behind schedule. "When we got there, nobody else was there and it didn't seem that anybody had been there," says Johnson. "It was a very sorry story."

The terrain around the dam was hilly, making the Lancaster hard to manoeuvre. It was to approach over a 180ft (54.9m) hill, swoop down, follow the length of the dam and drop the bomb as near as possible to the centre of the dam. The plane then had to climb immediately over a 300ft hill. Worse still, it was misty and a church steeple blocked what would have been the most direct approach.

It took 10 attempts before Johnson was happy with the bombing position. "I realised an easy way to become the most unpopular man there in double-quick time," he says. "But there was no point not doing the job properly."

The bomb, dropped from a height of just 30ft (9.1m), hit the dam. The damage was substantial but it was not breached, so the contents of the reservoir did not burst into the valley below.

The scale briefing model of the Sorpe dam

Johnson's crew had done its job, but only one other plane managed to get to the Sorpe dam. Even this was a replacement, the other crews intended for the job having been lost. It dropped its load, exploding near the dam, but again failing to breach it.

Yet it was a close thing, as Albert Speer, German minister of armaments, revealed, external in a report. "Fortunately the bomb hole was slightly higher than the water level," he wrote. "Just a few inches lower and a small brook would have been transformed into a raging river which would have swept away the stone and earthen dam."

The Dambusters lost 53 men and eight planes on that night. The Germans captured three more men.

After their drop, Johnson and his colleagues returned to Lincolnshire, 400 miles away. "I have to say the greatest satisfaction was on the way back," he says. "Our route took us back over what had been the Mohne dam. There was water everywhere. It was just like an inland sea."

The Mohne dam in North Rhine-Westphalia after being bombed

Landing at Scampton was difficult because of a burst tyre. An inspection of the Lancaster found that a bullet had pierced the rubber, also passing through a wing and the main body of the plane. It had missed the chief engineer's head by a few inches.

Some World War Two RAF crews displayed an almost oblivious attitude to death. It continues in Johnson. "What was going on didn't bother me in the least. My job was to get that bomb as near as possible to that mark. I was concentrating on that."

Born in Hamringham, Lincolnshire, in 1921, Johnson was the youngest of the six children of farm manager Charles Johnson. His mother died when he was three and his father treated him badly.

"I learnt something," he says. "I learnt that I had to do what I was told, or else. Apart from coping with the housework, including the cooking, I also had to help with the farm work - fetching in the cows.

"And of course I had to start school, about a mile down the road. I used to walk to that, occasionally run home at lunchtime, prepare the evening meal and then run back again." He remembers getting "good hidings galore".

Johnson escaped in 1933 when he went to a school in Hampshire set up for the free education of orphans of agricultural workers and those who had lost one parent. He excelled at sports, especially football, athletics and cricket. "That's the thing - I must have had some built-in co-ordination," he says.

George Johnson at the ceremony to mark the 70th anniversary of the Dambusters mission

Johnson joined the RAF in 1940 and applied to be a navigator but was selected for training as a pilot, although this did not suit him. He joined 97 Squadron, in which McCarthy served. "I was still no nearer that war that I had joined for, so I did the shortest course possible. That was to be a gunner."

Both moved to 617 Squadron, but Johnson faced a small disappointment. A week's leave he was due for completing a full tour of 18 operations was going to be cancelled because of training demands. Johnson had planned to marry Gwyn Morgan, whom he had met on a previous posting, during this period. McCarthy spoke to Guy Gibson. Johnson got his leave and the wedding went ahead.

The crews practised intensively for six weeks ahead of the mission. "We had no idea what the target was likely to be," says Johnson. "I suppose we should have had some idea because some of the training was carried out near dams in this country."

Aircraft windows were covered with sheets of blue celluloid and crews wore orange goggles to replicate the effect of moonlight when flying in the day. Johnson guessed the target would be the Tirpitz, Germany's biggest warship, external.

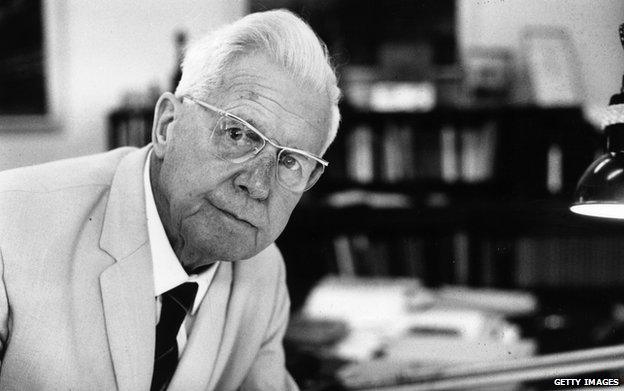

The man behind the "bouncing bomb"

Barnes Neville Wallis was born on 26 September 1887 in Ripley, Derbyshire

When WW2 began in 1939, Wallis was assistant chief designer at Vickers' aviation section

He developed a drum-shaped, rotating device that would bounce over water, roll down a dam's wall and explode at its base for the Dambusters raid

Became a Royal Society fellow in 1954 and was knighted in 1968. He died on 20 October 1979

The May 1943 mission was deemed partially successful because, although two dams were breached, the disruption to the German war effort was not as great or lasting as Barnes Wallis and Guy Gibson had hoped. However, the Dambusters' bravery was acknowledged.

Johnson received the Distinguished Flying Medal, one of 34 decorations for the squadron. He gained a commission, was eventually promoted to squadron leader and left the RAF in 1962, later working as a teacher and a mental health worker. He declined to attend The Dam Busters premiere in 1955.

Lord of the Rings director Sir Peter Jackson has been linked with a remake. Johnson met him a few years ago, Jackson promising to include the Sorpe raid if the project went ahead. "That meant more to me than anything else," Johnson says. "I don't put myself forward, but as long as people want to keep talking about it, I'll do so."

George "Johnny" Johnson and other people who grew up before World War Two discuss their experiences on Britain's Greatest Generation. The first episode is shown on BBC Two on Friday 8 May at 21:00 BST.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.