Smashed Hits: Louie Louie

- Published

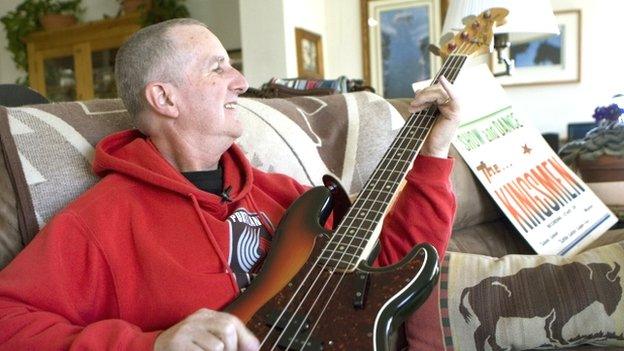

All these men helped contribute to the fame of Louie Louie

Jack Ely, singer with the Kingsmen, has died. He is best known for Louie Louie, a song inspired by the Caribbean which appeared, went away quietly and came back in a form so raucous that the American security services thought it should be outlawed, writes Alan Connor.

In 1964, the FBI began a 30-month investigation into the Kingsmen song Louie Louie. They were convinced that lurking in its mumbled vocals were unspeakable, almost literally unimaginable obscenities.

The lyric is really about a homesick mariner. How on earth did this happen?

The story starts in 1955, with Richard Berry, a doo-wop singer, waiting in a California ballroom's dressing room, listening to a Filipino band playing a cha-cha - more precisely, a song called El Loco Cha Cha. It began with the rhythm: cha-cha-cha, cha-cha.

"They were doing this real way-out Latin riff. It was that duh-duh-duh, duh-duh - and immediately I said hey, man, that's it: Louie Louie, Louie Louie."

He scribbled notes on a napkin, then kept thinking. Berry had a bedside tape recorder to capture any nocturnal inspiration and once he found a story, the song was there. The lyrics may be unfathomable in the most famous version, but Berry's couldn't be clearer - they're a sea shanty.

Louie Louie's garbled lyrics made the song's performers, the Kingsmen, a target for the FBI

Berry drew on songs where a lovelorn fellow misses his sweetheart, including One for My Baby and One More for the Road (set in a New York bar and made famous by Frank Sinatra). Berry shifted the location to an unnamed dock - Louie is a bartender whose ear is being bent by a sailor homesick for Jamaica and the "fine little girl" waiting there.

It's a touching miniature about a man who needs to leave a bar to catch a ship and, in Berry's original, decidedly non-raucous. It was the B-side to Berry's version of You Are My Sunshine and before long was found only in bargain bins.

Meanwhile, Berry proposed to his partner Dorothy Adams. She said yes, with one caveat. "I wanted a wedding ring set to show my friends I got married... But at the time he couldn't afford it. He said, I'll tell you what I'm gonna do. I'm gonna sell some songs, and then I'll get the ring."

Louie Louie was among a musical bundle that Berry sold for $750, a decision he remained philosophical about even in the 1980s, when he was surviving on welfare cheques after an attack by a neighbour's pit bull ended his job as a computer programmer.

Come the 1960s, the Pacific north-west of America had its own musical scene. The region's military tradition made it a melting pot of sailors keen to hear a mix of musical legacies at the "sock hops" and Battle of the Band nights where new sounds emerged.

Louie Louie had exciting chords out of La Bamba (in musicological parlance, rock 'n' roll tended to go back to the tonic chord before hitting the dominant). It had a Cuban rhythm more hypnotic than rock's backbeat, and it had its Caribbean setting. For places like Portland, Oregon, it was perfect.

Louie Louie became a concert staple, performed again and again in a single band's set. "You played Louie Louie and you had 100% of those people dancing," remembered "Little Bill" Engelhart of the Wailers.

The "garage bands" - youngsters who rehearsed in their families' basements and garages - added their own elements and soon the four or five "yeahs" after "me gotta go", the dominant chord played as a minor and the pre-guitar solo exhortation "Let's give it to them right now" were universally adopted. The garage scene was generally co-operative, and no Blurred Lines-type lawsuits ensued.

On a Monday evening in 1963, the Kingsmen heard Louie Louie and immediately resolved to learn it. "On Tuesday at school," remembered Ely, "I asked my black friends: Hey, where do you guys get your records?"

Ely picked up the words in time for a recording session which was, not atypically for garage bands, shambolic. One verse begins with a fluffed intro from Ely and ends with some of the band going into the chorus early. Drummer Lynn Easton mis-hits and clanks on a metal rim, and you can hear his fricative expletive on the recording.

The recording engineer Robert Lindahl was aghast at the racket: "You're going to blow up my equipment!" The band locked him out of the booth until they had a take. They then learned that they were to pay for the session themselves and after each member stumped up ten dollars, they went back to their homes.

While they would have preferred another go at it, it was the chaos of the Kingsmen recording that made Louie Louie enormous.

In fact, if Ely had not been slurring through a dental brace, the song might never have attained its greatest notoriety. FBI records do not reveal exactly how the record first came to their attention - a prank, perhaps, or a playground mishearing - but once the single was a hit, an urban myth spread.

If you played this 45rpm single at 33⅓, the story went, you could hear the "real words". And they were not demure, even if no-one was quite sure what they might be. Indiana radio stations banned Louie Louie as a result, a letter was sent to the then attorney general, Robert Kennedy and the resulting publicity meant that both teenagers and federal agents spent much of the early 1960s listening and re-listening to Louie Louie, searching for profanities.

The Kingsmen noticed that their audiences now included middle-aged men in suits and shades and were soon questioned by the Feds, apparently being told: "You know we can put you so far away that your family will never see you again."

They insisted that Louie Louie was innocent, but as ardently as they'd sought reds under the bed, and over the course of two-and-a-half years, the G-Men contrived a series of eye-wateringly unpalatable images, external and practices from Ely's mumbles.

As the files reveal, this was not the FBI's finest hour. They failed to interview Ely himself, who had since left the band, and they missed the genuine expletive uttered by Easton, focusing instead on words which, ironically, were the only chaste thing remaining from Berry's original. It was the Kingsmen's music that was startling.

In May 1965, a memo to director J Edgar Hoover concluded: "No further investigation is to be conducted in this matter." Legend has it that an investigator declared Louie Louie "unintelligible at any speed".

By now, Louie Louie, banned and apparently rebellious as well as loud and danceable, was an anthem, reinforced by its toga-party use in the 1978 John Belushi movie Animal House.

A Radio 2 programme, Louie and the G-Men, names it "second only to the Beatles' Yesterday as the most recorded song ever", appealing to artists from Barry White through Otis Redding to Iggy Pop (who used the FBI's dirty words on his version).

You can also hear echoes of Louie Louie in the stop-start of the Who's I Can't Explain and the Kinks' You Really Got Me... not to mention the Troggs' Wild Thing.

And come the 1980s, rock no longer rocked the establishment. The Washington state senate declared 12 April 1985 Louie Louie Day. Two years earlier, KFJC Radio in San Francisco played different Louie Louies for 63 hours, during which Berry met Ely for the first time.

It was also in the 1980s that Berry recovered some rights to Louie Louie. A collection agency tried to renegotiate the deal that Berry had signed in 1958 during negotiations to use the song in an advert for a sweet white wine.

Berry hadn't been conned but, unusually for the music industry, the decision went the songwriter's way, and he died a rich man in 1997.

Sources: Louie Louie: The History and Mythology of the World's Most Famous Rock 'n' Roll Song (Dave Marsh, University of Michigan Press), Love That Louie: The Louie Louie Files (Ace Records compilation linernotes by Alec Palao), Louie and the G-Men (BBC Radio 2, 15 Jan 2008)

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.