Will Gaudi be made a saint?

- Published

The extraordinary basilica of the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona has been under construction for more than 130 years - and there are those who hope that by the time of its completion, some 20 years from now, architect Antoni Gaudi will already be on the path to sainthood.

Every year, millions of tourists stop to gaze at an enormous tangle of arches and spires in the centre of Barcelona.

The Sagrada Familia basilica is under construction - as it has been since 1883 - so the exterior is slightly marred by scaffolding. When these tourists step inside, though, they encounter the captivating vision of the church's architect, Antoni Gaudi. Lining the nave are pale, tree-like columns that stretch up to the heavens, where they open up to form a complex stone canopy. The many stained-glass windows cast a dappled, shimmering light on the walls.

The overall effect touches many visitors deeply, sometimes unexpectedly.

"The lighting makes me withdraw into myself, feel introspective," says Lourdes Cirlot, an art historian at the University of Barcelona. "It creates a state close to mystical ecstasy. It is hard to say that a building can be miraculous. But if someone goes into the Sagrada Familia, and really believes that they'll be cured, it will probably happen."

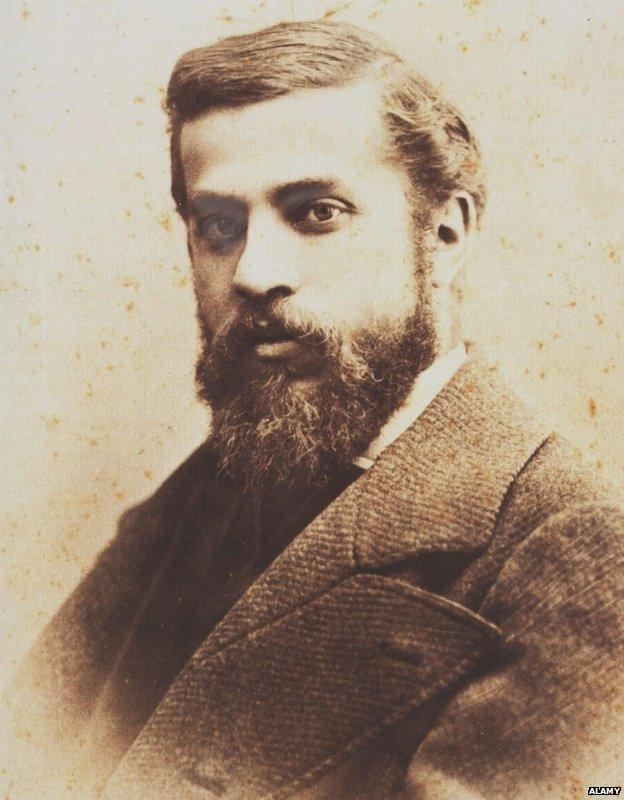

Throughout his life, Gaudi was inspired by natural forms such as the human body and trees

A campaign to make Antoni Gaudi a saint was launched more than 20 years ago, when a priest suggested to the Catalan architect, Jose Manuel Almuzara, that Gaudi would be a good candidate for beatification - often a stepping stone on the way to sainthood.

Almuzara formed the Association for the Beatification of Antoni Gaudi, and began work on the papers required to put his name forward to the Vatican for consideration.

One of the key documents - a biography - was written by the journalist Josep Maria Tarragona, who argues that making the Sagrada Familia does not in itself qualify Gaudi for beatification.

Gaudi was born rich but died poor

"The Roman Catholic Church has always used the best artists - such logic would mean that we would have to beatify Michelangelo or Mozart," says Tarragona. "This is not the question - the question is that the life of Gaudi is the life of an exemplary Christian. His life is the life of a saint."

Gaudi was born in Catalonia in 1852 into a wealthy family and a life filled, as Tarragona puts it, with "horses, opera, and the best restaurants". By the time he graduated from the architecture department of the University of Barcelona, he had begun to formulate his own unique visual language, inspired by pictures of pre-Islamic buildings from the Nile delta. Legend has it that when the director of the school of architecture, Elies Rogent, awarded Gaudi his degree, he said that he didn't know if he was giving it to a genius or a madman.

All his life, Gaudi was concerned about workers' welfare. He helped design the progressive Colonia Guell, a workers' community based around a mill, which boasted a hospital and schools, as well as Spain's first football stadium. After he started work on the Sagrada Familia in 1883, Gaudi built schools for the children of the workers and parishioners.

Gaudi's religious faith may have been inspired by his own art

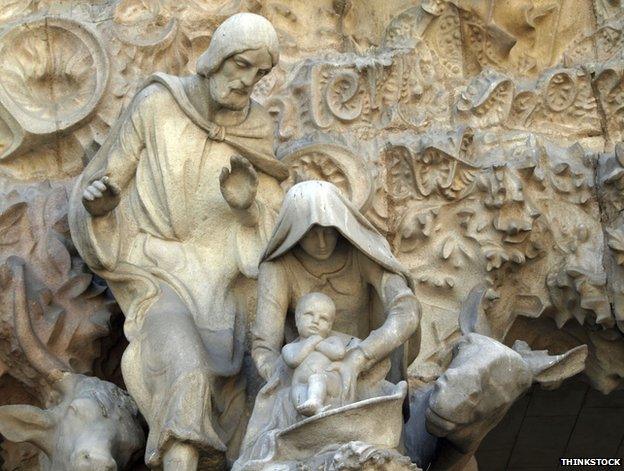

He was a controversial choice for the project because he was not a practising Catholic. But that began to change as the monumental basilica slowly took shape. Tarragona believes that it was while Gaudi was working on the joyful nativity facade that the architect "saw the person of Jesus Christ".

Slowly, his life took on an ascetic pattern. For lunch Gaudi would eat just a few lettuce leaves dipped in milk. When he was in his early 40s, he nearly died fasting for lent, and only began to eat again when a priest reminded him of his mission to build the basilica. He was to devote more than four decades of his life to it, turning down lucrative contracts in Paris and New York. When the project was in danger of running out of money, he frantically gathered donations to keep a small team of craftspeople working at the site.

Gaudi never married, though that had nothing to do with his religion, Tarragona says. He was simply unlucky in love.

His last few months were spent completely immersed in his work, living next to his workshop inside the church. When he was knocked down by a tram in June 1926, on his way to confession, it was initially thought that the gaunt man in shabby clothes was a beggar. Gaudi died three days later, leaving his remaining money to the basilica.

But Gaudi did not die a martyr's death. And in such cases, before beatification, the Vatican requires proof of a miracle.

Josep Maria Tarragona in Park Guell, designed by his hero Antoni Gaudi

"The problem is Gaudi hasn't caused a miracle," says Tarragona. "If you don't have a miracle, everything goes slowly."

In the years after Almuzara's association was formed in 1992 very little happened. The formal request for consideration of beatification has to come from the bishops in the diocese, but Tarragona says Catalonia's religious leaders were sceptical - worried, perhaps, that making Gaudi a saint might make the Sagrada Familia less attractive to non-Catholic tourists. The beatification campaign also faced opposition from secular Catalans, annoyed that the church was about to "claim" a national figure for itself.

But the campaigners' message penetrated the international press, and in time it reached the ear of Pope John Paul II. In 2000, His Holiness asked the archbishop of Barcelona, Ricard Maria Carles, if it was true that Antoni Gaudi had been a layman.

Most Catholic saints come from the clergy and the ranks of monks and nuns, but John Paul II was interested in the beatification of lay people. In 1980, he beatified Kateri Tekakwitha, a native American lay woman who has since been made a saint.

With clear signs of interest in Gaudi from the Vatican, things began to progress more quickly. In 2003, Catalonia's bishops gathered together a portfolio of research into the life of Gaudi and sent it to the Vatican. To their surprise, Vatican officials got back almost right away with an expression of interest. Gaudi was officially named a "Servant of God", the first step towards beatification.

In 2010, in a further positive sign for Gaudi's devotees, Pope Benedict XVI consecrated the Sagrada Familia. He seemed visibly moved by the building and in interviews with journalists, praised Gaudi's courage and creativity.

The consecration of the Sagrada Familia in 2010

The next step is for cardinals and theologians to vote on a decree regarding Gaudi's worth, which will then be put before the Pope. If Pope Francis agrees with a positive verdict, Gaudi will be deemed "venerable". This could happen in a couple of years, Tarragona says. There is speculation an announcement might be timed to coincide with the Pope's next visit to Barcelona, still unscheduled.

After Gaudi is declared venerable, the next step is beatification - but what about that elusive miracle?

The archbishop of Barcelona, Lluis Martinez Sistach, says a miracle of sorts has indeed occurred.

"From 1882 until now there has been no serious accident among builders working at such great heights," he points out, "nor among millions and millions of visitors to the temple under construction."

He adds that the Sagrada Familia has been the scene of some unexpected conversions among the international group of craftspeople who have been working on the building.

But what the pro-beatification committee is really looking for is a medical cure - one that leaves doctors astounded.

A few cases have come close. The first came to light about five years ago, when a woman with a perforated retina regained her sight. She was an artist from Gaudi's home town of Reus, and she said she had been praying for help from the deceased master. Her ophthalmologist said her recovery was completely exceptional, but some international experts were less impressed.

Jose Manuel Almuzara's organisation continues to await news of a miracle caused by Gaudi's intercession

A second example concerned a man with a tumour in his leg, who recovered in hospital without surgery. But again, there was some disagreement among the patient's doctors - some thought it was more exceptional than others.

For a while, Jose Manuel Almuzara thought that he might be bearing witness to a miracle himself. An architect friend contracted cancer, and after the two of them prayed to Gaudi for intercession, the man's condition improved. "The case was presented before the Holy See as a possible miracle and they passed it on to medical experts," says Almuzara. "The doctors said we had to wait for five years to make sure it didn't come back - but after three years it did and he died."

Despite these setbacks, Almuzara and Tarragona are optimistic that Gaudi is well on the road to beatification. Once he has been beatified, the prospect of sainthood will loom, if proof of a second miracle emerges.

The Rev Michael Witczak, Associate Professor of Liturgical Studies at the Catholic University of America says Gaudi's immense popularity will help. "The speedy beatification processes for Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa of Kolkata indicate to me that popular desire on the part of the ordinary faithful is a key element," he says. "I think the Catholic Church would like to canonise a layman who is also an artist and a craftsman, an engineer and a kind of mystic in his prayer life."

Gaudi lived to see the completion of only one of the Sagrada Familia's spires before his death in 1926. There are now eight, and another 10 will be built over the next 10 to 20 years, before the scaffolding finally comes down and tourists get an unimpeded view of the unique building.

The Sagrada Familia in 2010...

... and in 1940

When that day comes, non-Catholic tourists may have to jostle for space on the pavement with pilgrims who have travelled to offer prayers before Gaudi's bones.

"The current architect of the Sagrada Familia says, 'We'll finish the basilica first!' and we say, 'No no no, we'll finish the beatification first!'" says Tarragona - adding quickly that he's joking.

The Roman Catholic Church likes to take its time over these things, and it would be perverse to hurry Antoni Gaudi in death when he steadfastly refused to be hurried in life. As the architect once famously remarked of the constant setbacks and delays to his church's construction: "My client can wait."

Gaudi and the Miraculous Building was broadcast on Heart and Soul, on the BBC World Service. Listen again on iPlayer or get the Heart and Soul podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.