Viewpoint: Islam v feminism?

- Published

Why on earth would any girl abandon the liberties of a modern democracy to join the dark ages of IS? Huda Jawad attempts to offer an answer.

I was born in Baghdad and grew up in the United Arab Emirates and Syria before coming to settle as a teenager in London in the late 1980s. My parents were political activists during the time of Saddam Hussein and fled Iraq after the death sentence was imposed on them in absentia.

My mother has been a shining example of strength and endurance since her childhood. Her great-grandfather was an ayatollah, a famous religious jurist - Ayatollah Naini - and as a result she was raised in a deeply religious atmosphere.

However, Ayatollah Naini was a vehement advocate of constitutionalism and the superiority of reasoning, who described freedom of expression as God-given. Perhaps that explains in part why she was the first girl in her family to go to university and go on to have a career as a head teacher.

Before her, women in her family and social circle were not allowed an education, save for home-based Koranic and Islamic learning.

Likewise, my father grew up in southern Iraq into a family with a heritage for political and religious activism since the 1900s. Both my mother and father fought against the now defunct Baathist regime of Saddam Hussain.

As a result of this, my parents had to continually flee from where they had settled and make a new start in foreign lands, at least four times in their lives. Imagine doing that with young children who also happen to be girls.

While most of the time it was a life rich with adventure for us girls, largely due to our parents' ability to shield us from the emotional turmoil, there were some very dark moments in an otherwise happy childhood.

You may have by now picked up on a theme in my life story so far - that of identity politics. It certainly seems to be one way of explaining the journeys that I encounter in life.

A more recent experience of this was two and a half years ago when my uncle, an Iraqi Shia who lived in Syria for more than 30 years and married a Sunni Syrian woman, was kidnapped by rebel fighters outside his house in a southern suburb of Damascus.

He was taken as he was getting out of his car after driving home from work and was held captive for weeks under the most appalling conditions. He experienced awful treatment that to this date he cannot talk about but re-lives continuously in his nightmares.

When asked why he was abducted, his kidnappers simply said because he was Shia, even though he might have not described himself as such. Luckily for him my father and I have worked with a number of Islamists and religious activists from the Middle East, so knew who to turn to for help. To this day, we are indebted to the very few people who worked so tirelessly to secure his release.

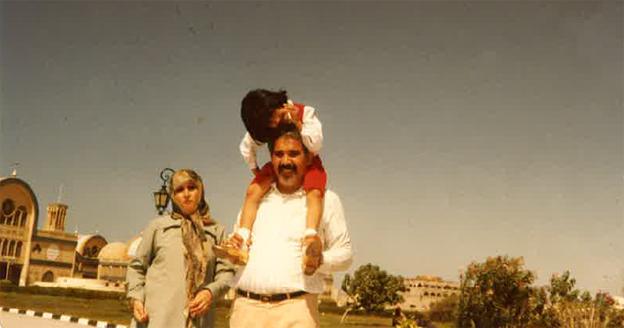

Huda with her father and mother in Sharja, UAE in the 1980s

So I watch with a mix of utter fascination and revulsion at the apparently continuous trickle of young women from Britain making the journey to Isis-controlled territory in Iraq and Syria.

Why would intelligent, seemingly well integrated daughters with bright futures ahead of them, enjoying the liberties granted by modern democracy, want to travel back in time to the darkest of dark ages? Where running water and electricity are a luxury. Where basic human rights such as freedom of movement or association are strictly regulated and in some cases cost you your life.

As the recent tragedies of capsized boats from Libya to Europe illustrate, hundreds of people literally risk their lives and that of their children to escape what these girls see as the ultimate Islamic utopia.

As someone who was born in the Middle East and escaped war and persecution as a child, knowing what it is like to be without water or electricity, or fearing that knock on the door at any moment, I cannot comprehend the choices these young women make.

As a committed Muslim and human rights activist, it makes me furious that these naive women accept and advocate the brutality and savagery committed by these terrorists and, furthermore, endorse them as Islamic or Sharia-compliant.

This desire to return to an imagined traditional and pure state of halal living as practised by the early generations of Muslims, free from the contamination of modernity and vice makes exceptions for smartphones, Twitter and Tumblr accounts. Surely I'm not the only one who can see these glaring contradictions?

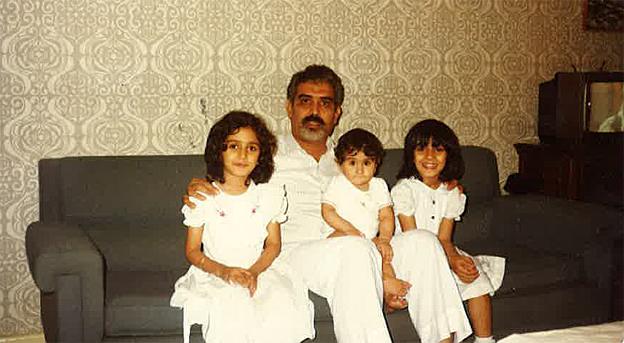

Huda with her father and sisters in the UAE before the family were expelled

Having said that though, I do connect with these young women at some level. I share their sincere desire for wanting to do the "right thing" and live a life where you are part of a greater whole working for the greater good. I share their yearning to learn more about who they are and where they fit in the world.

I share their rejection of the media's portrayal of Islam and Muslims as inherently violent. I share their frustration at experiencing prejudice and disrespect for being a Muslim. And for being a woman and a Muslim woman, whether by mainstream society or their own religious communities. I share their hunger for wanting to learn and their confusion about Islam.

Like the young women who are targeted to make the journey to Isis-controlled territory, I sincerely believed in my faith, in the innate way it seems to call for justice and equality and for collective social responsibility. For looking after the poor or the sick, for seeking the fairest and most just solution to problems - for the value it places on life, whether human or animal. On reason, on learning and on equality.

However, I know that according to clerics and men of learning, Islam sanctions some seemingly unjust rulings and opinions. How can it be that women have to seek permission to work or to marry?

How is it that forced marriage and violence in the family can be excused by the "natural right" of men over women? Why is it that women's movements and choices are so restricted? Why should women inherit half a share of that given to a man? These were all questions that I asked every day and was told that this was decreed by Allah in His Book.

British teenagers Amira Abase, Kadiza Sultana and Shamima Begum fled to Syria in February

Fearing disloyalty to my community, betrayal of my religion at a time when it was under a global siege and not wanting to commit psychological suicide, I never approached the Koran, never dared to open its pages for fear of reading something that I didn't like.

However, unlike these young women, a chance encounter with a work colleague, Yusuf, who is now a friend for life, gave me an opportunity that transformed my sense of God completely.

Yusuf thought I might be receptive to studying the Koran in a radically different way - a way where you critically engage with it, just as you are, without the need to spend years studying in a seminary or deferring to a scholar.

Our facilitator - that is what he calls himself rather than a teacher or an imam - gave us the framework for questioning and understanding meaning by using the Koran itself rather than any outside source like history, prophetic tradition, or commentary.

It was a thrilling experience. It enabled me to have a direct and unmediated conversation with God.

Yusuf and I set about inviting others who might be interested in this form of study. We were a diverse group of fellow Muslim believers - bankers, fashionistas, lawyers, medics, teachers and students.

We came to the collective realisation that our religious obligation is to ask questions and use our divine gift of reasoning to understand the words of God, and see how they relate to me and humanity now, then and in the future.

I have questioned and continue to question Allah and His words. My new-found relationship with God and His words has nourished and set me free. It highlighted the importance of taking responsibility for our religious learning. It also shows the power invested in those who read and interpret scriptures for and on our behalf.

A few years after my start on this journey of reclaiming God I began working in a secular domestic violence charity in London. My work brought me in contact with hundreds of women and children who were survivors of the most horrific and abhorrent form of abuse and betrayal of trust.

These women came from all ethnic, racial, educational, economic and religious backgrounds. Domestic violence did not discriminate, whether you were young or old, secular or religious - what mattered was that you were a woman.

Many of the women that I worked with identified with a faith or a religion. Some were told that their faith sanctioned this abuse, some were told that they were being tested by the Divine. Almost all saw their faith as a source of support and empowerment.

What struck me was the extent to which religious tradition can be used to excuse violence or challenge it. I was enraged to hear that Islam was used in the most perverse ways to maintain women's vulnerability and persecution and enable the perpetrators, who are usually men, to coerce and control them.

It was at this moment that all the various strands of my life's work came together to ignite my passion for Islamic feminism. The answers to the questions I detailed earlier became clear - women's voices from the interpretation and understanding of Islam were absent.

Since then I have come to learn of Muslim feminists who have in the past 10 years produced rigorous and religious paradigms that question long-held beliefs and presumptions about central tenets of religious laws and the handful of Koranic verses that have been used to discriminate against women and girls.

Like the victims of domestic abuse, jihadi brides are similarly indoctrinated and vulnerable.

They yearn for an empowering space where their religious identity is welcomed, nurtured and seen as integral in their ability to establish the so-called khilafah based on an intolerant, literalist, patriarchal and medieval interpretation of fiqh or jurisprudence. It is a fiqh which is an interpretation or understanding of sharia that is not only an excuse for violence but that restricts and defines women's relationship to men and society according to standards far from what we know as equality and justice today.

Looking at their blogs and tweets it's clear that they seek evidenced religious opinion on what they can "do", where they belong and how they can actively contribute to creating a just society. This poses a timely and urgent opportunity to engage them in looking at how Islamic feminism can provide them with the intellectual and religious tools they seek.

It will enable them to seek answers that honour their faith while also honouring their gender, maintaining their dignity whilst excelling in helping society and those around them. They can remain faithful while challenging the narrative that argues that salvation and the role of a Muslim woman can only be fulfilled by raising children and building a "home" to men who think that sexual exploitation, slavery, abuse, murder and torture are the religiously authentic way of building a society.

How different would things be if women owned and were part of the production of religious knowledge. Surely it's no coincidence that one of the first acts of social policy and justice in the Prophet's message was the banning of female infanticide so ubiquitously practised at birth by Arabs at the time.

Therein lies a lesson for us all.

Huda Jawad's viewpoint will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4's Four Thought programme on Wednesday at 20:45 BST. You can catch up via the iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.