A family's struggle to bring a Pearl Harbor sailor home

- Published

Edwin Hopkins was on the USS Oklahoma when it was sunk during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was buried in a grave of unknown sailors, and his family believed his body was never identified. But it was - and now, 74 years later, there is a plan to bring him home.

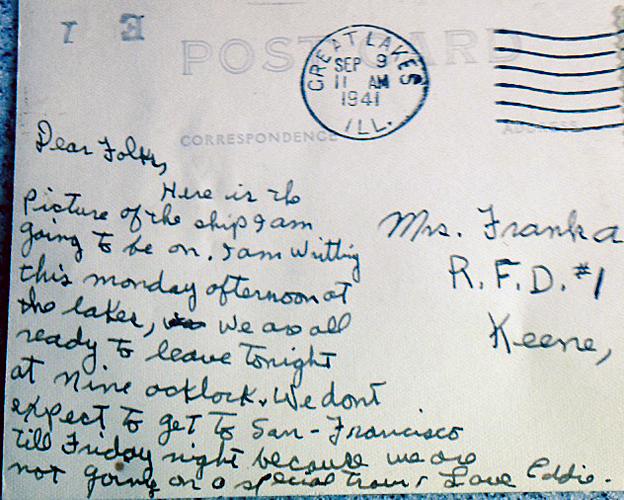

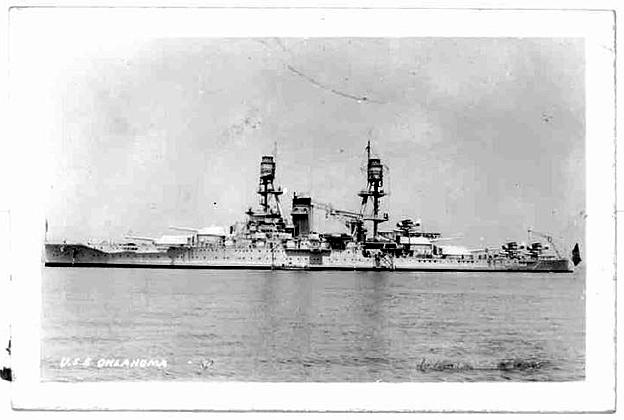

In September 1941 Hopkins wrote a postcard home, with a picture of the battleship he was going to serve on.

"He said he was going off to board the Oklahoma for Hawaii. He sent that to his mother and that was it," says Tom Gray, Hopkins' cousin. The family still treasures the card, as their last contact with the teenage sailor.

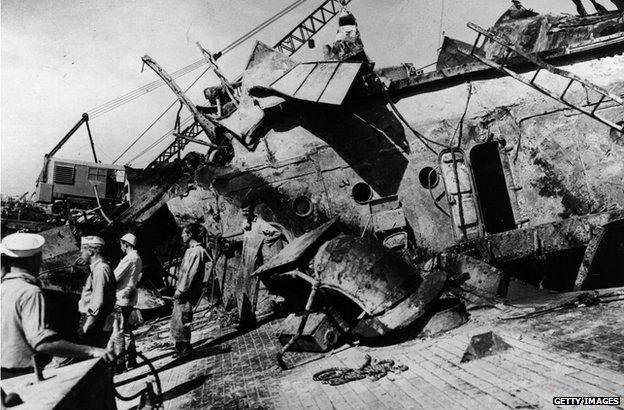

Three months later, almost to the day, the Oklahoma was the first ship to be hit during the surprise Japanese assault and capsized in less than 15 minutes.

"Edwin was a fireman third class and he was probably deep down in the hold when the ship was torpedoed. When the ship went down that was the last my family heard of him until 2008," says Gray.

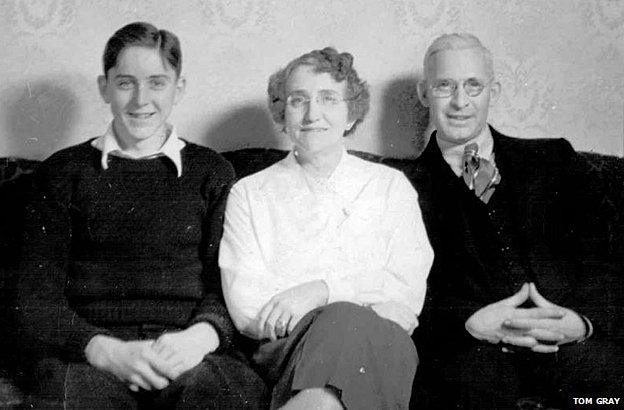

Hopkins grew up in Swanzey, New Hampshire and was remembered by the family as "just a great guy, the life of the party", says Gray.

When Americans began to enlist in large numbers after the fall of France in June 1940 and the start Battle of Britain a few weeks later, Hopkins' older brother, Frank Jr, and one of his cousins went into the US Navy. Before long, at the age of 18, Hopkins followed them.

"They came home and Edwin did not. It was an open wound," says Gray.

"They always honoured him and they kept him alive through stories. My entire family, we're all raised around Edwin Hopkins. I think it's a tribute to my family that they passed the emotions and the feelings on to the next generation. He lives in our minds and we never met him."

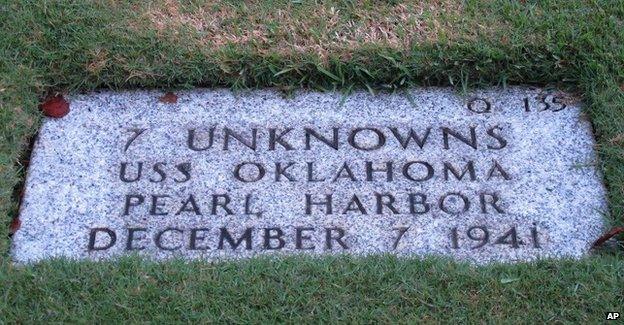

Out of the 429 servicemen on the Oklahoma who died that day, only 35 were identified at the time.

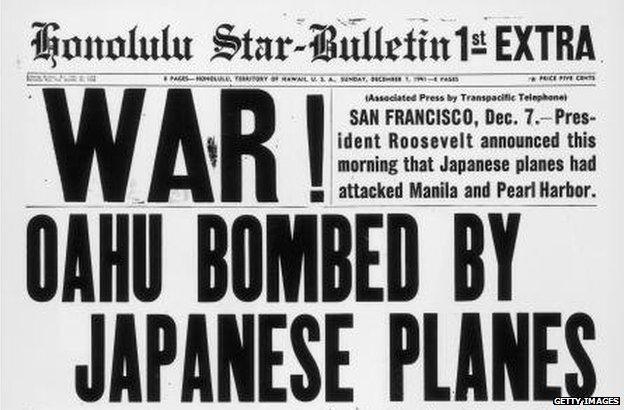

The attack on Pearl Harbor caused the US to join the Second World War

Many other bodies were brought up during salvage operations carried out between 1942 and 1944, and were buried later in caskets marked "unknown" at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii.

So far as Hopkins' relatives knew, he was among those unknown sailors.

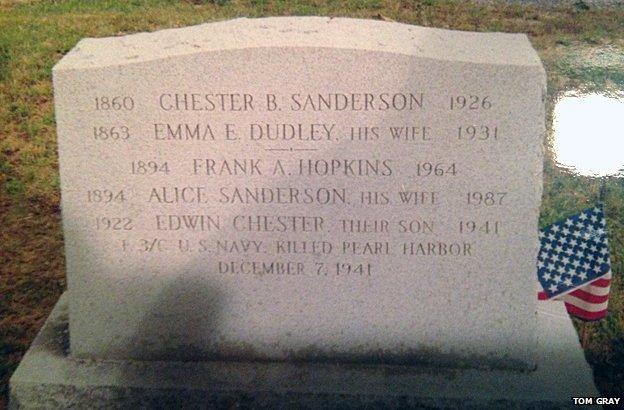

"His mother was probably in some type of shock and she refused to believe that he was gone. She had his name engraved on the family stone because she said she was waiting for him to come home and she wanted him there with her," says Gray.

Then, during the 1990s Ray Emory, a Pearl Harbor veteran, carried out painstaking research on the Oklahoma "unknowns" and discovered that 27 sailors had been identified during a salvage operation in 1943.

Buried later that year in Hawaii's Halawa Naval Cemetery they were moved in 1949 to the newly opened National Memorial Cemetery in the Punchbowl, the crater of an extinct volcano in Honolulu.

"When it came time to put them in to the Punchbowl there was a lot of bureaucratic problems and unfortunately the answer at the time was to just take all the remains and put them in as unknowns," says Gray.

Emory had evidence there was a record of Edwin Hopkins being named at the Halawa Cemetery in 1943 but then listed as "unknown" at the National Memorial.

Gray first found out about this discovery when a cousin got a call from a group of veterans and family members of those who had died on the Oklahoma telling her about Emory's research.

"When all my cousins found out everybody just cried because it's an amazing thing. My father's younger sister is 88 years old - she's the only person left alive who ever knew Edwin. When I told her she was just broken up, she just couldn't believe it.

"From 2008 until right now my cousin and I have been basically banging on the Navy's door saying please exhume these people, we want to bring these people home, we know who they are. The Navy had various reasons why they didn't want to do it. I understand those reasons but we really want him home," says Gray.

In 2003 the US Navy exhumed one of the graves Emory said contained a casket containing five of the newly named unknowns. The sailors' remains were found inside and sent home.

But Gray says the Navy was surprised to find other unidentified human remains in the casket too and refused to undertake any more exhumations, in order to avoid disturbing more graves,.

"The Navy just put a stop to everything," says Gray.

He then enlisted the help of politicians, including eventually a coalition of US senators, spearheaded by Chris Murphy and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, and Kelly Ayotte of New Hampshire.

Last month they succeeded in their campaign to get the Department of Defense to exhume the remains of nearly 400 Oklahoma servicemen, over the next five years, with the aim of identifying them and giving them individual burials.

"Without their help this historic decision would not have been made," says Gray.

"I know my cousin is in grave P1003. I know there are two caskets in that grave, there's five men in each casket from the Oklahoma so I even know who my cousin's buried with in there. There are 18 families across the US that are involved in this and we're all in touch with each other."

He is looking forward to the day when the "long journey" his family has been on will come to an end.

"It's a real emotional thing and it's a case of being very happy but also a case of sadness - Edwin's brother died in February 2008 and we got the call that Edwin had been found in March, so he missed it by a month.

"The only thing I can say is that his mum and dad put his name on that headstone up there and it's going to happen and that's a real sense of accomplishment for all of us. It's just a wonderful thing."

More on the Second World War

Tom Gray spoke to Weekend on BBC World Service.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.