The Quiet Zone: Where mobile phones are banned

- Published

Anyone driving west from Washington DC towards the Allegheny Mountains will arrive before long in a vast area without mobile phone signals. This is the National Radio Quiet Zone - 13,000 square miles (34,000 sq km) of radio silence. What is it for and how long will it survive?

As we drive into the Allegheny Mountains the car radio fades to static. I glance at my mobile phone but the signal has disappeared.

Ahead of us a dazzling white saucer looms above the wooded terrain of West Virginia, getting bigger and bigger with every mile. It's the planet's largest land-based movable object - the Robert C Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) - 2.3 acres in surface area, and taller than the Statue of Liberty.

But it needs electrical peace and quiet to do its job.

The dish's 2,200 individual panels reflect radio waves into the receiver horns

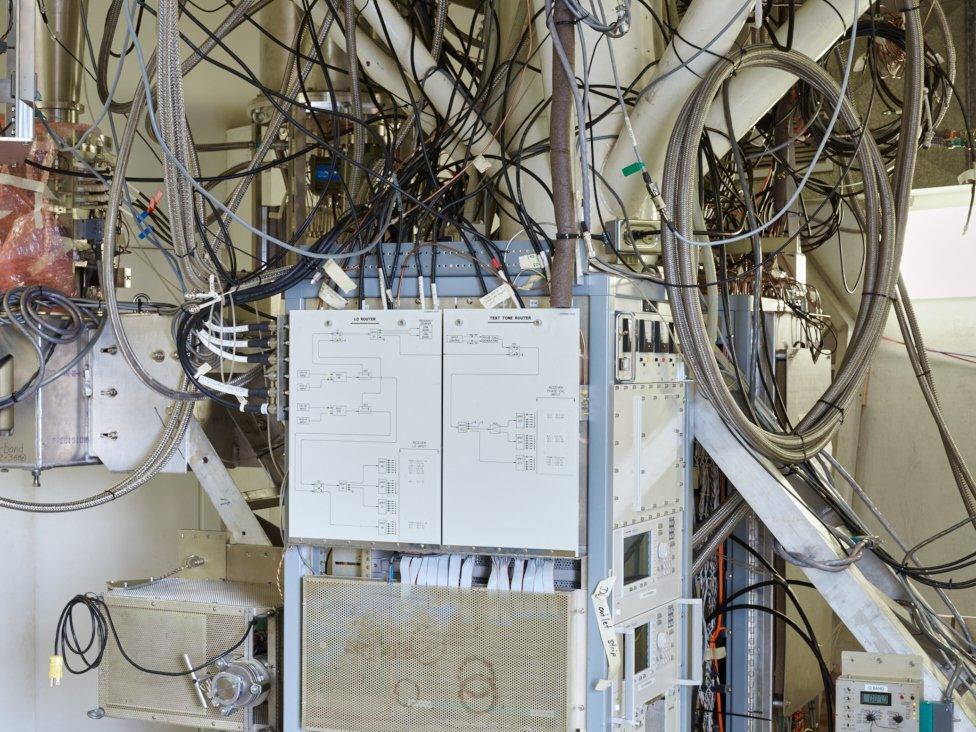

All signals captured by the GBT are fed into the receiver room - receivers are cryogenically cooled and kept between -269C and -258C to minimise internal interference

The Quiet Zone, established in 1958, protects it from interference - and also the National Security Agency's main listening post at Sugar Grove nearby.

The GBT is highly sensitive and can detect radio waves emitted milliseconds after the birth of the universe. But when a signal has travelled so far, from so long ago, it can easily be drowned out.

"The telescope has the sensitivity equivalent to a billionth of a billionth of a millionth of a watt… the energy given off by a single snowflake hitting the ground," says business manager Mike Holstine. "Anything man-made would overwhelm that signal."

Hence the Quiet Zone, whose residents live a very different kind of life from most other Americans.

Not only are there no mobile phones, there are no baby monitors, microwave ovens or wireless doorbells.

Mike Holstine

Chuck Niday with his patrol vehicle on Horseback Ridge

"Any kind of electrical appliance can cause interference," says Chuck Niday, who patrols Pocahontas County, home to 8,000 people at the heart of the zone. He's constantly on the lookout for rogue radio-frequency interference (RFI).

"One I can think of that could cause a lot of problem is a vacuum cleaner - the type of motor they use generates a lot of sparks," he says.

Anyone caught hoovering with a faulty machine will be politely asked to desist.

"We have no enforcement powers, that's done by the federal agency known as the Federal Communications Commission. All we can do is ask them to turn off the offending device and 99% of the time they do," he says.

In one case, observatory staff bought a farmer a new heater for his dog pound when it transpired the old one was leaking unwelcome radio waves.

No petrol engines are allowed within a mile of the GBT because they use spark plugs. And no electronics can be used at a nearby airstrip. "We just have a windsock and a tetrahedron so that they know which way the wind is blowing," says Holstine.

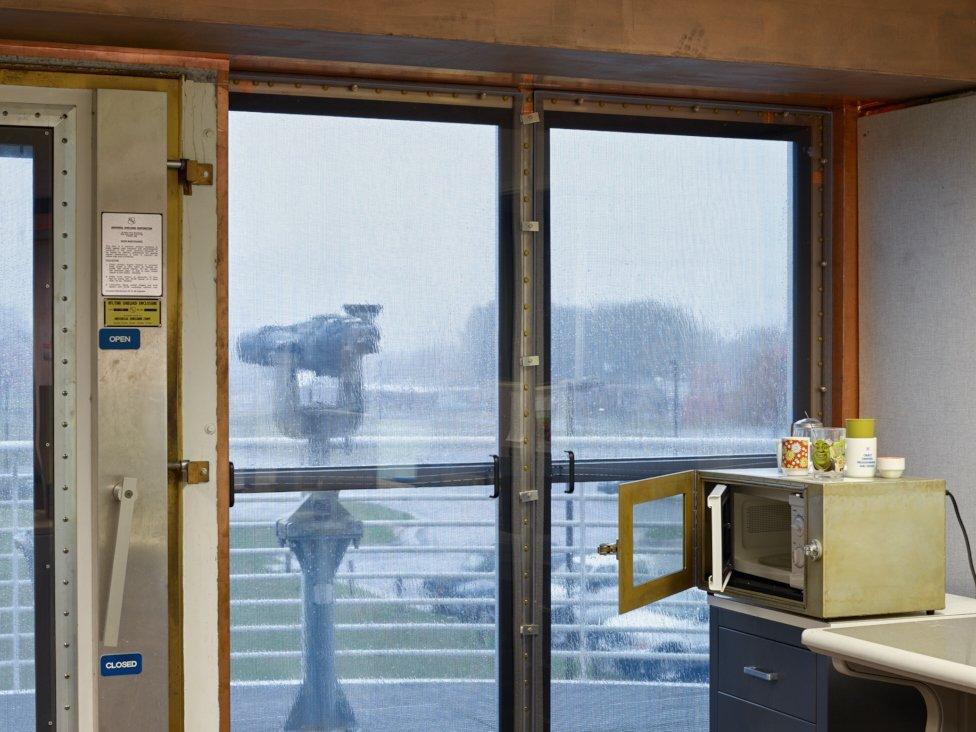

There are a few exceptions to the rule though - emergency services are allowed to use one particular frequency for example. And staff at the GBT have a microwave where they can heat up their lunch - but it's housed in a special cage to stop radio waves leaking out.

And when he's not out on patrol, Niday and his wife present a jazz programme on Allegheny Mountain Radio. He managed to shield the antenna from the telescope - a complex operation that wouldn't be possible for mobile phone signals.

Chuck Niday

Bluegrass tracks dominate the playlist

The GBT control room has a microwave which sits inside a specially designed Faraday cage - the whole of this room is lined with copper as well

While the rest of the US is constantly plugged in - checking emails and posting updates on social media - the lack of mobile technology in the Quiet Zone leads to a different mindset.

"We do have broadband internet at our homes," says GBT site director Karen O'Neill. "We can access the internet the same as anyone - the difference is that when I leave my desk the internet doesn't follow me.

"When I watch a soccer game, every parent on that field is watching the kids playing soccer, nobody is looking at their cell phone, no-one is worrying about that."

And while I'm here, I no longer feel the constant compulsion to check my mobile - it's not like being in a remote spot with a frustratingly slow or expensive connection, it's a completely different way of life.

In this quiet pocket of North America there is a strong sense of community where conversations aren't interrupted by phone calls, status updates or notifications.

"You really don't see that struggle with the parents here where they talk to their kids and say, 'You've got to put the phones away,' and the kids go, 'Do I have to?' and they're sneaking them under the table and doing everything they can to text their friends," says O'Neill.

What becomes of the Quiet Zone in the 21st Century depends to some extent, on the future of the GBT. The site costs $14.5m (£9.2m) a year to run - and the National Science Foundation which finances it has warned it may reduce its contribution significantly by 2017.

So while the staff at Green Bank hunt for signals from the birth of the universe, they are also searching for funding.

"They want to use that money to build new telescopes in Chile," says Holstine.

"We're trying to find alternative projects that will bring in money and right now the most promising is tracking satellites."

It's not just the 200 staff employed to maintain and operate the GBT whose survival depends on the telescope - there are sheet metal workers, cleaners, caterers and guest houses where visiting scientists stay.

Kevin, once a champion power lifter in Africa, sells fuel, fishing tackle and wedding cakes

Bobby owns Trent's convenience stores

Ebby has worked in this shop for more than half a century

There are tensions within the zone though - finding a public phone box that works here isn't easy and young people in particular are anxious to get their hands on smartphones with fast mobile internet connections to the rest of the world.

The fixed-line access they currently have is very slow - with no high-speed broadband it feels like you're stepping back 15 years. And phone companies aren't willing to invest in laying better cables for such a small community.

But the status quo suits others well - there is a small but significant population of "electro-sensitive refugees" who have moved into the area.

"We can't be where crowds of people are - we have to stay away from people because most people are carrying cell phones and that harms us," says Diane Schou who calls herself a "technological leper".

She used to live on a farm in Iowa but after a mobile phone mast was built nearby, she became ill. "I had gotten hair loss - I thought I was getting older. I had a rash - I thought that was something I ate. My vision changed - I thought maybe it's getting older... My skin got wrinkled - OK getting older. I got a headache and that's when I went to the doctor because I rarely have headaches."

She started experimenting and says that whenever she went home the headaches returned. "It's like somebody hit me on the head with a sledgehammer."

She says that since she came to Green Bank her health has improved considerably - and she knows 57 other people who have found relief there from similar symptoms.

Local physician's assistant Rachel Taylor has seen a rise in the number of people with similar stories in recent years. She says she hasn't seen any "solid concrete studies that have proven it," but is convinced "they have something going on".

Whatever happens to the GBT, there's still Sugar Grove - the National Security Agency listening post to the north. Reports have suggested some of the facilities there may close this year but Holstine expects much of the base to remain operational.

If the GBT is decommissioned, Sugar Grove will have to take over patrolling the area, but it will not need to be so strict about stray radio waves around Green Bank.

Some think it's possible that could open the way for unofficial wireless devices to sneak in and change the "quiet" way of life.

GPS is allowed in the Quiet Zone - it receives signals from satellites and the NRQZ does not have authority over space-based transmissions

View from the GBT: the smaller telescope is operated by the same team and the mountains act as a barrier to outside signals

Images by photographer Emile Holba - to see more images from this series click here, external.

Welcome to the Quiet Zone with Emile Holba is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 from Monday 18 May to Friday 22 May at 12:00 BST.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.