The decline of the British front garden

- Published

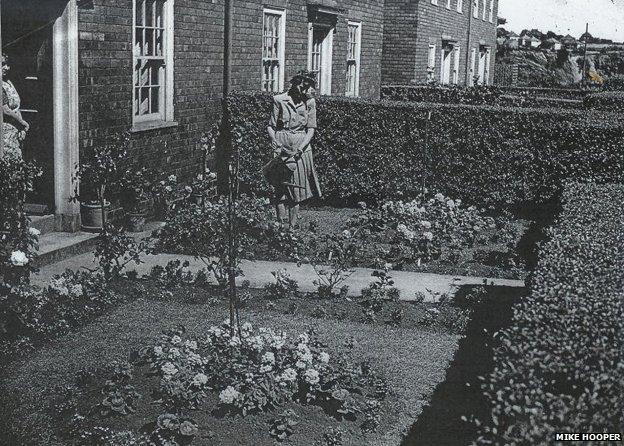

A typical suburban front garden in 1968

The Royal Horticultural Society says British front gardens are disappearing. Why are people paving over their lawns?

When people imagine a classic British front garden, they may first think of a small slice of well-tended grass. Perhaps with a box hedge.

But over the past 10 years the number of front gardens with gravel or paving instead of grass has tripled, now making up a quarter of all houses, a survey for the RHS shows.

There's an environmental cost. Paving increases the risk of flash flooding - instead of grass and soil soaking up moisture, it runs straight off paving and overwhelms drainage systems. TV makeover programmes have been partly blamed for the decline, external in gardens by encouraging people to replace greenery with patios.

This street from the Becontree Estate in Dagenham shows the rise of paving

"If vegetation is lost from our streets there is less to regulate urban temperatures," explains Rebecca Matthews Joyce, principal environmental adviser at the RHS. "Hard surfaces absorb heat in the day and release it at night, making it hot and difficult to sleep."

There are other environmental issues too. Apart from offering privacy, trees and plants absorb dust and provide a place for birds to nest and insects to feed.

Most people don't want to lose their front garden but are being forced to use it for other purposes, says Paul Gilmour, a horticultural researcher on BBC Two programme Gardeners' World. People need a storage area for their waste and recycling bins. They also need parking.

But the same estate was once known for its immaculate garderns

"Having a front garden offers 'kerb appeal'," Gilmour says. That's a term for the attractiveness of a property when viewed from the street. "If you're selling a house and you have a beautiful garden you're quids in. More affluent areas tend to have larger trees and nicer front gardens.

"I like my front garden because it is a different palette of plants and a different look to my back garden."

But for the people who change their front garden, practicality trumps aesthetics. They accept coming back to a house that looks less attractive. But they're also changing the look of the whole street.

On the Becontree estate privet hedges had to be kept at regulation height

As our social networks have expanded to become more complex, we have become less concerned about how we are perceived by our neighbours, says Dr Joe Moran, a social historian.

"When it became common for people to have family cars and when the TV arrived with other mod cons, the life of the street became less important as people became more directed on things that happened in their houses.

"There may be a sense in which we are less concerned about keeping up with the Joneses - what the neighbours think - as we don't know them as well."

Prizes were awarded for the best-kept gardens

And people may feel they're not really losing a space they could use. Front gardens look nice, but does anybody actually spend much time there?

"The traditional front garden was not somewhere you would sit out," says Moran. "It was more something you kept nice for other people around you.

"On working-class terraces, it was common for women to scrub the kerb with a donkey stone [traditional scouring block] as it was very much about keeping up appearances. If you don't know your street as well, you're not going to be as concerned about having a well kept front lawn."

Decades ago, there might be strict rules on what householders could do with their front gardens in certain areas. The Becontree Estate in Dagenham, east London, was one such place.

Originally built as council housing after World War One, it was, at one point, apparently the largest council housing area in the world. And the front garden had to be maintained a particular way.

A resident of the estate maintains the front garden

"You had to cut the grass, you had to trim the privet hedges. You had to maintain it or the council would be on to you," says Barry Watson, who has lived on the estate for all of his 72 years. "Your neighbours would report you and [the council] had power to evict you - and they did."

But now, much of the estate has followed the UK's trend. Where once there were endless neat front gardens, now many are effectively concrete parking bays. "The changes are drastic," says Watson.

A London Assembly report from 2005 entitled "crazy paving" said that two-thirds of London's front gardens were either partially or wholly covered in an assortment of paving, bricks, and concrete.

Few planning controls exist to stop lawns from being paved. But applications to councils for "dropped kerbs" to allow cars to cross over to the front garden give some indication as to the scale of the change. According to the RHS, nearly 120,000 such applications have been made during the last five years.

Watson says the main changes came after Margaret Thatcher allowed people to buy their council houses and make changes more freely - as he himself did, paving over most of his front garden to allow easier access for his disabled wife Shirley.

"My next door neighbour completely covered the front garden with crazy paving, as mine mostly is now," he says. "The whole street is crazy paved. I'm the only one who has any garden to speak of on my side."

There are currently more than 38 million vehicles licensed on the UK's roads. Fifty years ago, there were 11 million.

A car spends around 80% of its life parked at home, according to a report by the RAC, external. The scramble to cement is a result of supply and demand. And estate agents will often cite off-street parking as a plus point to potential buyers. In areas where parking is at a premium, it can add value to a property.

According to the English Housing Survey, external, privately rented accommodation is most likely to have been paved, with one in five plots "hard landscaped" from 2001-2007.

The number of families with both parents working increases the likelihood of two-car driveways, and could also explain the preference for something which requires little upkeep.

"It's much easier to maintain," says Moran. "If you have a family in which both people work, it's harder to mow the lawn every weekend so a paved front garden is easier to look after."

Watson laments the impact of the loss of greenery. "I don't like to see the whole garden covered over - but I can't criticise because I've done it myself."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox