Greggs: The baker that is stopping selling loaves

- Published

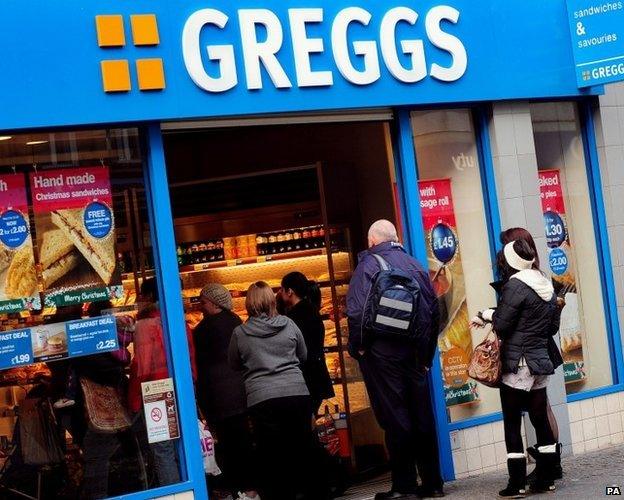

Greggs, Britain's biggest chain of bakeries, has stopped selling loaves in many of its stores. It's a move that reflects changing habits, writes Justin Parkinson.

Loaves were the future once. In 1951, John Gregg, who had spent more than a decade delivering yeast to homes in Newcastle via bicycle so that housewives could bake their own bread, changed his business model.

He started his own shop with a bakery at the rear, selling loaves at the front. The firm grew rapidly, based on what, at the time, represented increased value and convenience.

There are now 1,671 Greggs shops, with the bread they sell made at nine regional bakeries, with 20,000 people employed in total. But, despite keeping the Twitter handle @GreggstheBakers, many of its stores have stopped stocking loaves.

The decision has been revealed in a series of exchanges, external with customer Andrew Denny, who said: "Tried to buy a loaf of bread yesterday. To my astonishment the local Gregg's said they didn't sell it any more." The company responded: "Sorry Andrew. If products aren't selling well, we take them off to allow for other products to be sold."

After Denny said this made Greggs more like a "snack bar" than a baker, it added that "we do still sell bread in some of our shops :-)".

The company says it's now focusing on "food-on-the-go products, including sandwiches", which are "freshly prepared in store every day and made using our own bread". "While loaves of bread can still be purchased in a number of our shops where we see high levels of customer demand," a spokeswoman adds, "we also understand that customer shopping habits and needs are changing and have adapted accordingly."

Ready-made sandwiches are certainly huge business, with sales increasing by 4.2% in the last year to £7.85bn, according to the British Sandwich Association.

The average price of a ready-made sandwich is £2.14, it says. This is cheap compared with most fast foods, especially when part of a lunchtime deal, including a drink and a snack, for not much more money.

The concentration on takeaway sandwiches and other ready-to-eat food appears to be working for Greggs, which earlier this year gave its shareholders a £20m dividend, external after sales exceeded expectations.

But food journalist Andrew Webb, external worries that bread, part of the human diet for around 9,000 years, is in danger of becoming "little more than a carbohydrate glove" to prevent sandwich fillings from spilling. "We treat bread these days a little like we treat tea or milk," he says. "We just want the cheapest available. It's the product that gets thrown out the most."

Overall sales of loaves in the UK fell from the 1950s to 1980s, according to the Federation of Bakers. They stabilised during the 1980s and, since the early 1990s, have risen and fallen again. Still, 83% of consumers still buy packaged, sliced loaves, according to the market research company Mintel.

Lunch breaks have become shorter, external, meaning more people eat in the workplace, in a style Webb calls "al desko". Supermarkets have entered the lunchtime market, forcing Greggs and its competitors to focus, particularly in city-centre areas heavy on office workers, on sandwiches and other convenience foods, he adds.

Greggs also sells pasties, sausage rolls, salads and pizza slices, among other things. Yet sandwiches dominate front-of-shop displays.

"We continue to eat a lot of bread, but often we hardly notice it," says Webb. "The decision by Greggs is another step towards this."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.