The US police chief fighting to end racial tension

- Published

Cincinnati Police Chief Jeffrey Blackwell has made major policing changes in less than two years

As America searches for ways to tackle the huge issues surrounding race and policing, one police chief believes he has the answers - and others are starting to listen.

A Cincinnati police officer crosses a basketball court, but the 20 or so men playing, mainly African American, barely glance at him.

"Oh it's the chief," one mutters, and then carries on with the game.

They have got used to seeing Chief Jeffrey Blackwell, and that has been part of his plan.

As I stroll with him through the city's Lower Price Hill district, which has faced serious poverty and crime issues for years, some wave at Chief Blackwell, others come over to chat about what's happening in the city or how he's doing.

It's a world away from all the images of confrontation between officers and protestors America has seen of late.

"The problem is that in America, police officers don't know these young people," Chief Blackwell says.

"Some of them don't understand the difference between poverty and criminality, and I would imagine you would get some officers to assume that 30 kids in a park, as boisterous as they are, might mean trouble brewing, when they are just having a very competitive game of ball."

Since he took charge of the Cincinnati Police Department less than two years ago, it has been the mission of Chief Blackwell, the son of a black father and white mother, to make headway in breaking down some of the deep mistrust between black communities and the police.

Walking the beat in Cincinnati

"We want our officers to have more compassion for people, especially people who need us the most," he tells me.

"And those are generally people who are black, people of colour and people in inner-city America."

In a strategy that Chief Blackwell himself describes as "risky", he took officers out of emergency response units and out of their patrol cars, to put them on the streets to engage with communities.

"We have got to be concerned with elevating people's lives, and helping people," he says. "I think this country is telling the police profession very loudly they want to see us change."

He's referring to nationwide protests after a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, shot dead an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown.

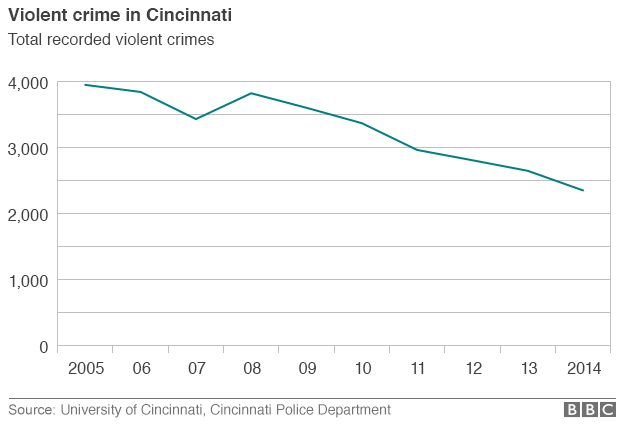

Cincinnati is one of several US cities where crime is on the decline

Numerous cases have since hit the headlines, including 25-year-old Freddie Gray, who died while in custody of the Baltimore police. His death lead to days of unrest.

"Every city in this country is one incident away from Baltimore and one incident away from Ferguson," says Chief Blackwell.

"Racism has been allowed to grow and fester and manifest itself throughout entire criminal justice system."

He was horrified to see the way police officers dealt with the protests in places like Ferguson, particularly criticising the use of snipers and dogs.

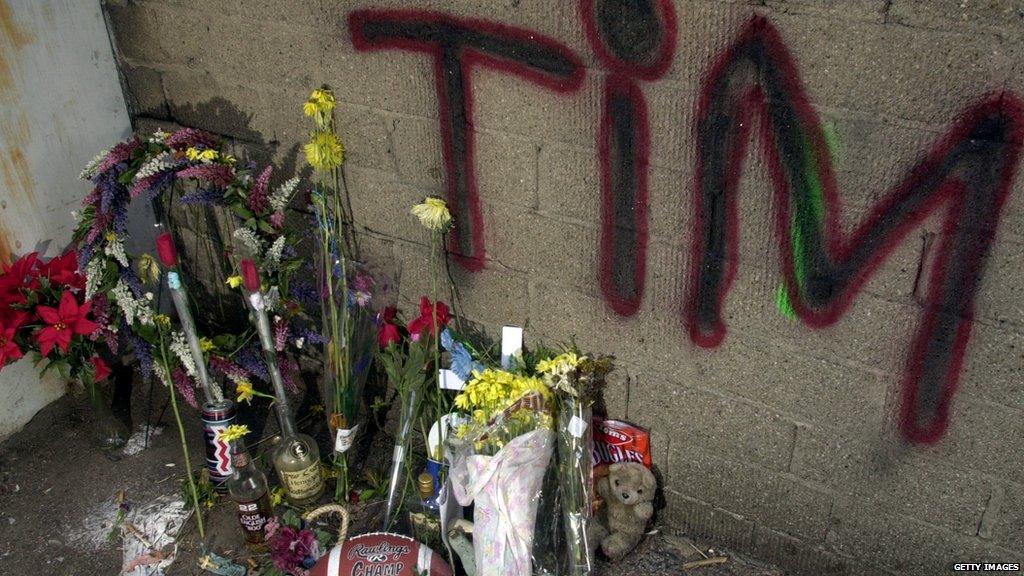

Cincinnati had its own riots in 2001 after a police officer shot and killed Timothy Thomas, an unarmed black teenager.

The death of Timothy Thomas by a Cincinnati police officer sparked riots in 2001

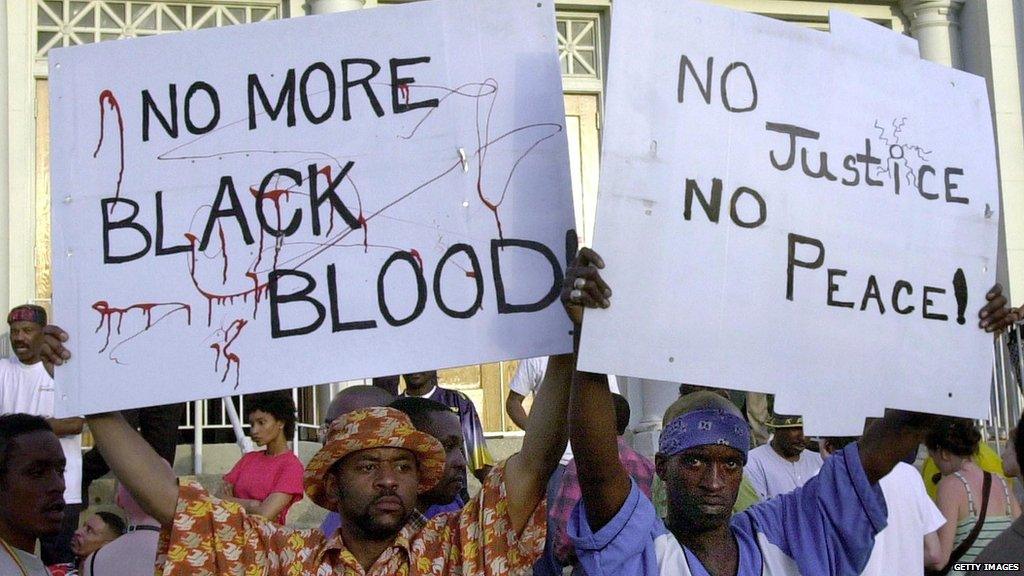

Dwight Patton says the protests were "the boiling point" after lengthy mistreatment by police

The shooting led to three nights of rioting in which dozens of people were injured, more than 800 arrested and a police curfew was imposed.

"Police would point their shotguns in our faces, they fired rubber bullets," Dwight Patton, one of the protest leaders 14 years ago.

"I can relate to what went on in Ferguson. Just like there, this was the boiling point, the culmination of our frustration at the way we were being treated," Mr Patton says.

The officer, Stephen Roach, was acquitted of all charges in Thomas' death, but the Cincinnati police force was made to change.

The city established a police complaints body and trained officers to better deal with the mentally ill.

They also made officers complete paperwork every time they pulled over a vehicle, including recording the race of those they stopped.

"To my mind the greatest change was in the mindset of the police department," Patton says.

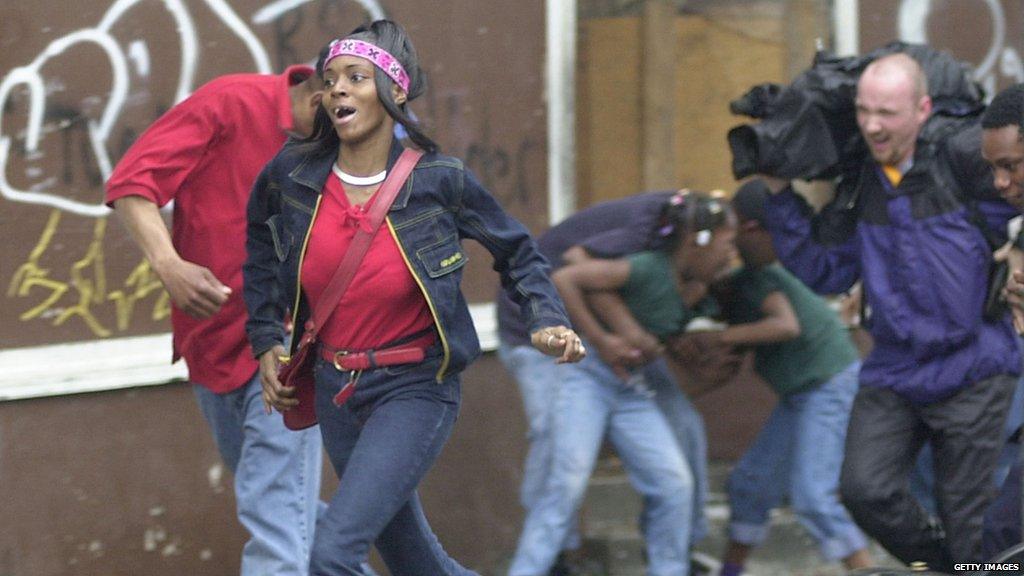

Residents run from officers shooting rubber bullets in 2001

Cincinnati was forced to change its policing after the death of Thomas and its response to protesters

"Whereas before they were very punitive, now they seem to be cooperative with the community when possible."

"They are courteous, they do their job and the knee-jerk shootings or beatings of people doesn't seem to occur as frequently."

Patton still feels there is a long way to go, but believes Chief Blackwell is moving in the right direction.

And his changes have caught the attention of many, even at the highest level of power in the US.

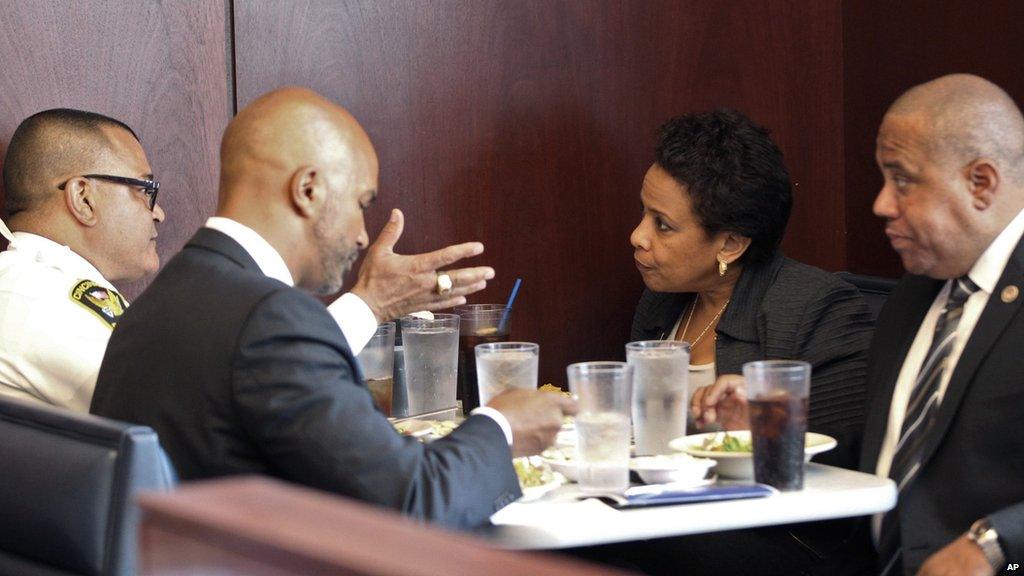

The new Attorney General, Loretta Lynch, made a trip this week to speak to the Cincinnati police chief, saying she wanted to see for herself the "groundbreaking work" they were doing.

US Attorney General Loretta Lynch visited with Chief Blackwell on Tuesday

But not everyone is convinced things have changed.

"You telling me the police say they aren't racist is like you are telling a sheep that the wolf says he's going to change his ways," says David Walker, 22, who we meet in a northern suburb of Cincinnati.

"Sure, all cops aren't bad, but I can't stand there and work out who is good and who is bad," he says.

"With everything that is going on, when I see a police officer I just tell myself to stay calm even though I'm doing nothing wrong.

"Sometimes I think I should I call my mom real fast and tell her I love her, just in case he decides to follow me around the corner and do something," he says.

Chief Blackwell says it is understandable black communities and some of his officers will take time to trust each other.

"I just tell myself to stay calm even though I'm doing nothing wrong," David Walker says

"There's a lot of work to be done on both sides," he says. "Police officers are very resistant to change, just as the community sometimes is very resistant to change."

"Police have been part of the racial problem in this country for the past 200 years...but we can change where policing goes from here."

He says he is building on the reforms previously forced on Cincinnati by changing the ethos of policing in his city.

Cincinnati no longer "over-polices" entire black neighbourhoods, instead focusing on individuals who have had run-ins in the past.

Chief Blackwell is also asking officers to think much harder before drawing their guns.

But with more than 50 police officers already having been killed in incidents across America this year, he has been criticised for potentially endangering the lives of officers.

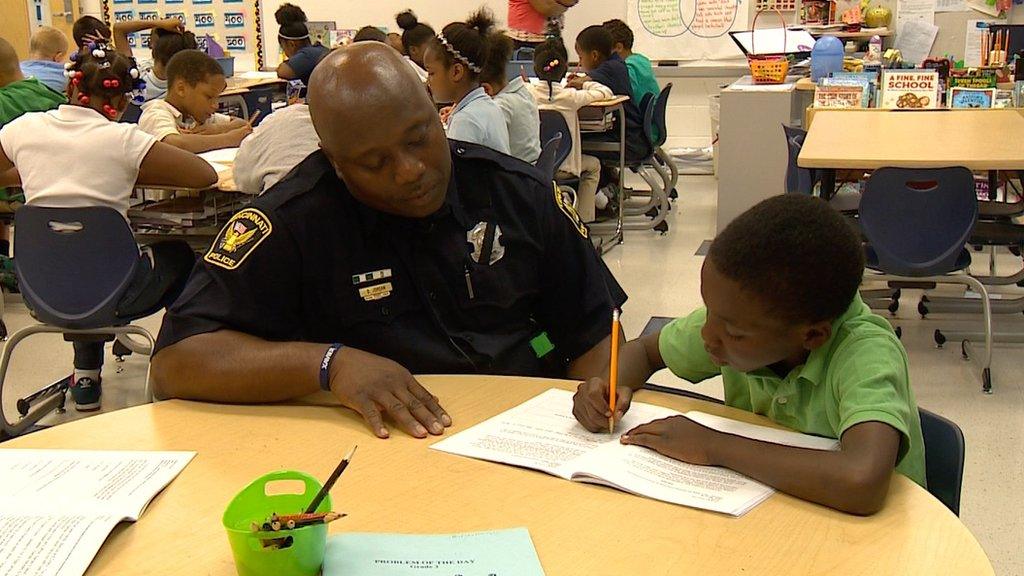

Part of Chief Blackwell's programme is to bring officers into schools not to police - but to mentor students

As part of National Police Memorial Week, Chief Blackwell gave out Medals of Valour to two of his officers.

They had shot, but not killed, an armed man who had burgled a home. Even in Cincinnati the line between heroism and vilification can be a fine one.

But Chief Blackwell says his style of policing, as "guardians not as warriors," is one that many of his peers will reject.

"I would categorically say that the majority of police chiefs in this country are still tied to law 'enforcement'."

"We are servants of the community, we are supposed to be uplifting people and helping communities become stronger and better," he says.

"We can't do that if we're only focused on chasing bad guys."