How US students get a university degree for free in Germany

- Published

While the cost of college education in the US has reached record highs, Germany has abandoned tuition fees altogether for German and international students alike. An increasing number of Americans are taking advantage and saving tens of thousands of dollars to get their degrees.

In a kitchen in rural South Carolina one night, Hunter Bliss told his mother he wanted to apply to university in Germany. Amy Hall chuckled, dismissed it, and told him he could go if he got in.

"When he got accepted I burst into tears," says Amy, a single mother. "I was happy but also scared to let him go that far away from home."

Across the US parents are preparing for their children to leave the nest this summer, but not many send them 4,800 miles (7,700km) away - or to a continent that no family member has ever set foot in.

Yet the appeal of a good education, and one that doesn't cost anything, was hard for Hunter and Amy to ignore.

"For him to stay here in the US was going to be very costly," says Amy. "We would have had to get federal loans and student loans because he has a very fit mind and great goals."

More than 4,600 US students are fully enrolled at Germany universities, an increase of 20% over three years. At the same time, the total student debt in the US has reached $1.3 trillion (£850 billion).

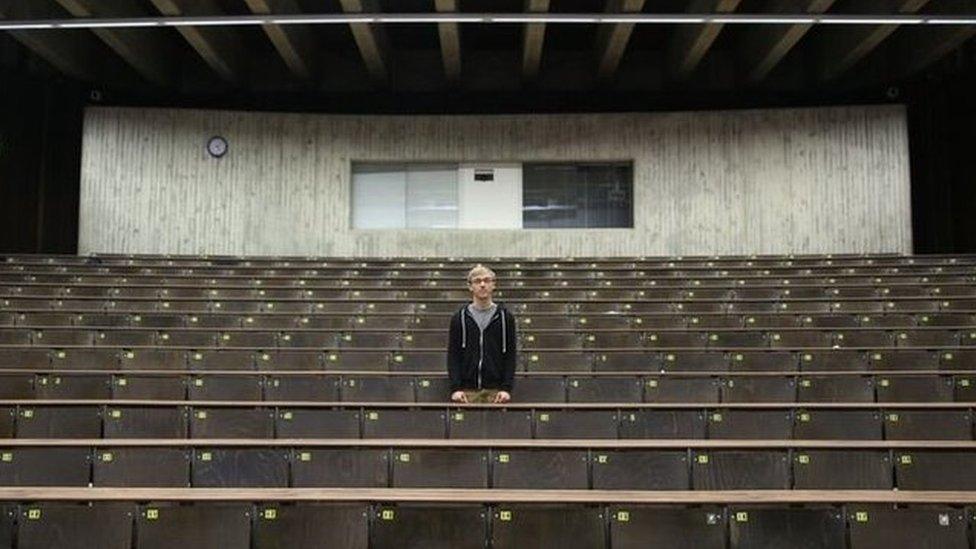

Each semester, Hunter pays a fee of €111 ($120) to the Technical University of Munich (TUM), one of the most highly regarded universities in Europe, to get his degree in physics.

Included in that fee is a public transportation ticket that enables Hunter to travel freely around Munich.

Health insurance for students in Germany is €80 ($87) a month, much less than what Amy would have had to pay in the US to add him to her plan.

"The healthcare gives her peace of mind," says Hunter. "Saving money of course is fantastic for her because she can actually afford this without any loans."

To cover rent, mandatory health insurance and other expenses, Hunter's mother sends him between $6,000-7,000 each year.

At his nearest school back home, the University of South Carolina, that amount would not have covered the tuition fees. Even with scholarships, that would have totalled about $10,000 a year. Housing, books and living expenses would make that number much higher.

The simple maths made Hunter's job of convincing his mother easy.

"You have to pay for my college, mom - do you want to pay this much or this much?"

How Hunter saved $60,000 over the course of his four-year degree

'Mind blowing'

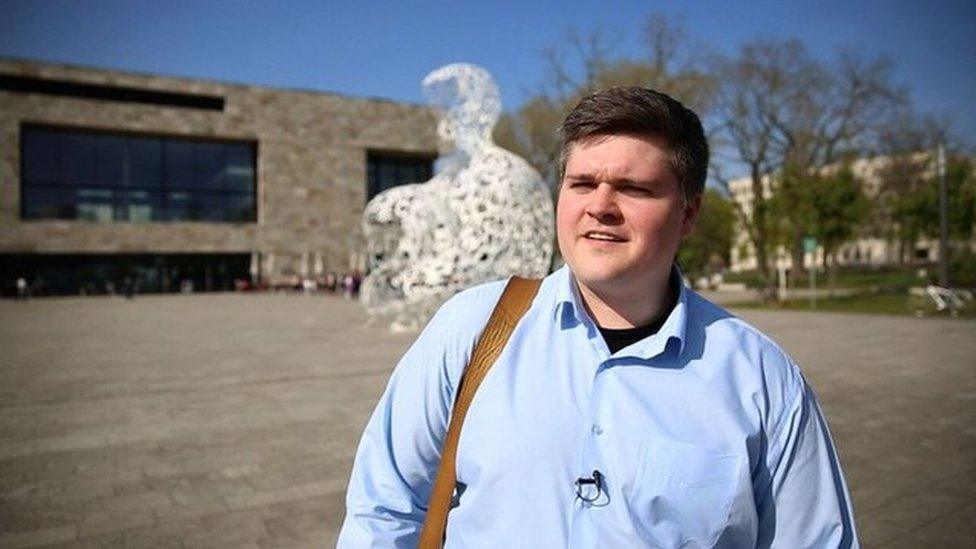

The financial advantages of studying in Germany have not been lost on other US students. Katherine Burlingame decided to get her Master's degree at a university in the East German town of Cottbus.

A graduate of Pennsylvania State University, Katherine spent less than €500 ($570) a month in Cottbus, which included housing, transportation and healthcare. On top of that she received a monthly scholarship by the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Council) of €750 ($815) which more than covered her costs.

"When I found out that just like Germans I'm studying for free, it was sort of mind blowing," Katherine says.

"I realised how easy the admission process was and how there was no tuition fee. This was a wow moment for me."

In the 2014-2015 academic year, private US universities charged students on average more than $31,000 for tuition and fees, with many schools charging well over $50,000. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, Sarah Lawrence University is most expensive at $65,480.

Public universities demanded in-state residents to pay more than $9,000 and out-of-state students paid almost $23,000, according to College Board.

In Germany, tuition fees of €500-1000 were briefly instituted last decade, but Lower Saxony became the last state to phase them out again in 2014.

Students pay a fee to the university each semester to support the student union and other activities. This so called 'semester fee' rarely exceeds €150 and in many cases includes public transportation tickets.

Sprechen Sie Deutsch?

When Katherine came to Germany in 2012 she spoke two words of German: 'hallo' and 'danke'. She arrived in an East German town which had, since the 1950s, taught the majority of its residents Russian rather than English.

"At first I was just doing hand gestures and a lot of people had compassion because they saw that I was trying and that I cared."

She did not need German, however, in her Master's programme, which was filled with students from 50 different countries but taught entirely in English. In fact, German universities have drastically increased all-English classes to more than 1,150 programmes across many fields.

US students in Germany

4,654

fully enrolled at German university

61%

pursue Master's degree

-

29% Languages, Cultural Studies

-

27% Law, Social Sciences

-

12% Engineering

-

10% Math, Natural Sciences

In 1999, European Union members signed the Bologna Accords, which called for uniform university degrees, and established a Bachelor/Master system across Europe. With hundreds of thousands of students from Portugal to Sweden freely travelling abroad, studying and getting degrees in other countries, English became the common language.

At Hunter's university, the Technical University in Munich, 20% of students are non-German. The University president is keen to have every single graduate programme offered in English, and only in English, by the year 2020.

"You can feel sad and think it's a pity that we are losing our own mothers' tongue in the technical disciplines, but that's the development in the world," says Wolfgang Herrmann.

He acknowledges that people wanting to study philosophy and other cultural sciences would still have to be taught in German.

"But in the technical disciplines you could say the world is easier."

Still, to thrive in daily German life, students and experts alike told the BBC that German language skills are crucial.

"If you go to a pub or supermarket and you don't understand what everyone is saying in the long run you don't feel comfortable," says Sebastian Fohrbeck, Director of Scholarships at DAAD.

Most universities offer subsidised language programmes, and in some cases a certificate proving the applicant's German skills is required to apply to certain courses or scholarships.

What you need to know about studying for free in Germany

What's in it for Germany?

One student in Berlin costs the country, on average, €13,300 ($14,600) a year. That number varies according to the field of study. With no tuition fees that expense is shouldered by the individual states, and ultimately the German taxpayer.

Of 170,000 students in the capital city of Berlin, more than 25,000 are from outside Germany. In simple math, that's €332.5 ($364.3) million that Berlin spends a year on foreign students. The question is why?

"It's not unattractive for us when knowledge and know-how come to us from other countries and result in jobs when these students have a business idea and stay in Berlin to create their start-up," says Steffen Krach, Berlin's Secretary of Science.

German students do not need to worry either, he says, because the city has increased capacities massively in recent years at its universities and there is enough space for everyone on campus.

How to apply in Germany

1. Do you have what it takes

Sometimes a high school diploma with a 3.0 GPA is all you need. Click through this link, external to see if you qualify for direct admission or for a preparatory course.

Prep courses, called Studienkolleg, external, take one year and culminate in an assessment test.

2. Find a university

DAAD offers a comprehensive database, external with the option to look for programmes taught in English only.

Find out where your university ranks, external in terms of academics, teacher support, job market preparation, etc (requires a free registration).

Contact the local office, external for international students if you have questions.

Research shows that the system is working, says Sebastian Fohrbeck of DAAD, and that 50% of foreign students stay in Germany.

"Even if people don't pay tuition fees, if only 40% stay for five years and pay taxes we recover the cost for the tuition and for the study places so that works out well."

For a society with a demographic problem - a growing retired population and fewer young people entering college and the workforce - qualified immigration is seen as a resolution to the problem.

"Keeping international students who have studied in the country is the ideal way of immigration. They have the needed certificates, they don't have a language problem at the end of their stay and they know the culture," says Fohrbeck.

Can it last?

Yet with more students from the US and across the world turning their attention to a cost-effective education in Germany, questions arise how long this system can be sustainable.

At Technical University in Munich, Dr Herrmann can imagine a future when international students are asked to pay in order to keep up with the global competition.

"If we ignore the question of how to finance an outstanding university in the future we will not continue to have outstanding universities in Germany." Dr Herrmann says. "Education, teaching and research are very intimately connected with money. That's a global law we cannot escape."

An amount of €5,000-10,000 ($5,400-11,000) would be appropriate, says Dr Herrmann, who thinks these fees would also see an increase in services for international students.

But students and educators alike are warning that even the smallest fees could bring an end to the flow of talent to Germany from certain parts of the world.

"I definitely think a limited amount would be fair for American students," says Katherine, who finished her degree in Cottbus and is now living in Berlin.

"But they also have to consider students who come from developing countries that can't pay these kind of tuition fees."

In the capital city of Berlin, the most popular destination for international students, the state government says it has no plans to introduce fees anytime soon.

"We will not introduce tuition fees for international students," says Krach, the Secretary of Science. "We don't want the entry to college to be dependent on your social status and we don't want that the exchange between countries is only dependent on the question of finances."

In the US, meanwhile, there won't be any movement to create a system similar to the one in Germany as long as people flock to expensive schools for their reputation.

"College education in the US is seen as privilege and expected to cost money and in Germany it is seen as an extension of a free high school education where one expects it to be provided," says Jeffrey Peck, Dean of the Weissman School of Arts and Sciences at Baruch College/CUNY. "It's a totally different attitude in what we expect as a society."

Personal recommendations

After Jay Malone received his Master's degree in the West German town of Siegen last year he decided to stay in the country and start an agency called Eight Hours and Change which advises US students who wish to study in Germany.

Selling a free college degree to US high school students and their parents isn't a hard undertaking.

"Most of the questions are 'is it really true?' and then I have to spend five minutes reassuring," says Jay. "But slowly people have wrapped their mind around it and have started associating Germany with this system."

One of the biggest stumbling blocks for potential applicants is convincing them that the quality of education can be high even though it is free.

"Nobody in the US wonders why high school is free," says Sebastian Fohrbeck of DAAD. "Our economic success proves that we are not completely wrong. If you really train your manpower and womenpower well, this is of extreme benefit for the whole country.@

Katherine also decided to stay after graduation and moved to Berlin to work for a start-up association. Sitting in a trendy cafe where the bartender speaks little German but fluent English, Katherine says this experience made her question the way education is financed in the US.

"I can't imagine ever thinking that my children one day are going to end up in thousands and thousands of dollars in debt when they can come to Germany and have no debt and you can live so cheaply as a student."

Even during stressful times studying in a foreign language in Munich, Hunter has not regretted the step he took, and already knows he wants to stay in Germany after graduation.

"I miss my family all the time, but there was never a moment where I thought I belong back home. Germany as a whole fits so well to my needs in life."

His mother Amy is okay with that as long as her son finds a good job and doesn't struggle. She does wonder why her own country was not able to give him a similar education at a price tag that this single mother could afford.

"I feel like my child is getting an absolute wonderful education over there for free. Betrayal is too strong of a word, but why can't we do that here?"