Spice: The dangerous alternative to cannabis

- Published

The designer drug Spice has been blamed for five university students being admitted to hospital, two of whom were left in a critical condition. But what is it and why is it so popular?

Two students at Lancaster University are recovering having been admitted to hospital in a critical condition after taking an "unknown" substance. Police are looking into what this was, but initial reports suggest it was Spice, the name commonly used to describe a laboratory-created cannabis substitute.

While simulating the effects on the brain of cannabis, which is banned in many countries, including the UK, its chemical make-up is different and its side-effects, as yet, little studied. Some experts say it can be up to 100 times as potent, external as the drug it mimics.

The European Union has warned of "acute adverse consequences" for users' health, which are said to include increased heart rates, seizures, psychosis, kidney failure and strokes, external. Deaths have been reported in Australia, external and Russia, external.

In the US, 19-year-old Connor Reid Eckhardt fell into a coma and died after taking some last year. "Parents, educate yourself on synthetic drugs," his family has urged, external. "They are taking the world by storm. Do it for Connor. Do it for your kids. Because every life matters."

But some users say in online forums that they have not experienced severe side-effects.

Cannabis-simulating substances - or synthetic cannabinoids - were developed more than 20 years ago in the US for testing on animals as part of a brain research programme. But in the last decade or so they've become widely available to the public.

In the UK, part of the popularity of Spice is that, with slight tweaks of the chemicals used, suppliers can stay ahead of the law, with the authorities having to respond by banning the latest incarnation.

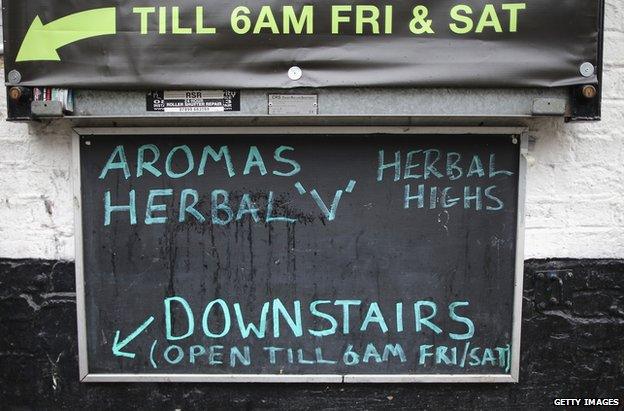

Usually synthetic cannabinoids are sprayed on to herbs, which are smoked in the same way as ordinary cannabis. Supplies of these are available online or in "head shops". Spice was originally a brand name but has become a generic term applied to such products. The substance also comes in tablet form and as a liquid to use in e-cigarettes.

The Home Office is looking at imposing a blanket ban, external on all synthetic cannabinoids to end what Trevor Shine, commercial director of the drug-identification company Tic-Tac, calls "a constant game of cat and mouse" with suppliers. "When they ban one type, other ones that are outside the ban are created," he says. "It may be more so with synthetic cannabinoids than with any other drug."

Home Office minister Mike Penning says more than 500 new drugs have already been banned and that "early-warning systems" have been upgraded. "A blanket ban would give our police and law enforcement agencies greater powers to tackle the trade in these harmful substances as a whole, instead of a one-by-one approach," he adds.

Most are thought to originate in China. During 2013, the European Union's Early Warning System identified 81 new psychoactive substances, of which 29 were synthetic cannabinoids, external. A survey in Michigan suggests they are the second-most-popular drug among high school students, after cannabis.

And yet many believe that synthetic cannabinoids are significantly more dangerous than cannabis.

It's been suggested that some artificial cannabinoid compounds found in Spice act more strongly on, and bind more closely to, external, the brain's receptors than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the chemical responsible for most of the psychological effects of ordinary cannabis. This leads, scientists say, to more powerful and unpredictable side-effects, because of links to the heart, breathing and digestive systems, external.

Another concern, according to the US government, is that there may be harmful heavy metal residues in mixtures. But there has been little testing to establish this.

The authorities in many countries are struggling to deal with what has become a big business, while purchasers often suffer from a lack of reliable information.

"You don't know what's in them and what quantities of chemicals are used," says Mark Piper of the toxicology test provider Randox Testing. "It's very much backroom and underground chemistry that's behind all this. There's no pharmaceutical use for them. They weren't even designed to be used on humans."

Recreational cannabis use has been illegal in the UK since 1928, so the appeal of legal highs, despite appearing to pose greater health risks than cannabis itself, is obvious. "Why would you risk buying an illegal drug when there are 20 legal varieties available?" says Shine.

Piper worries that users are confusing legality with safety. In fact, some older drug-takers, who would have tried cocaine, amphetamines or cannabis in the 1980s, are trying synthetic cannabinoids because "the kids are doing it, so it must be all right", he says. "But it certainly has addictive qualities," Piper adds. "It's incredibly dangerous."

For help and support on drug use, visit the BBC Advice pages or drug advice service Frank, external.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.