The strange day my father saved Harold Wilson’s life

- Published

Harold Wilson died 20 years ago, on 24 May 1995. He would have died many years before that, writes novelist Isabel Wolff, had her family not saved him from drowning.

As a child I spent many family holidays on the Isles of Scilly, 28 miles off the Cornish coast. We'd spend our time walking, cycling and, best of all, rock-pooling.

But where we would normally expect to catch a few shrimps and the odd crab, there was one memorable year when we pulled the Leader of Her Majesty's Opposition out of the water.

It was 10 August 1973 and we were enjoying a bike ride around the largest island, St Mary's. I was with my parents, my elder brother Simon, 16, then a pupil at Rugby School, his best friend Robert, and my younger brother, Matthew, who was 10.

As we cycled along a path above an isolated bay, Matthew spotted an empty rubber dinghy racing out to the open sea. As we watched it speed towards the horizon we wondered whose it was and why it was loose.

Isabel Wolff

Suddenly my father said that he thought he'd heard a cry. Sure enough, above the buffeting of the wind we could just make out a distressed male voice.

My father cupped his hands and shouted: "What is your trouble?"

"I can't get into my boat," the voice answered. "Fetch a dinghy!"

We pedalled down to the bay as fast as we could. My father yelled: "We'll get to you in a few minutes. Can you hold on?"

"Yes - for a bit," came the faint reply.

While Robert sped off to alert the Coastguard, Simon found a dinghy - but it had no oars. My father hurriedly looked around for a pair but then, further off, saw a wooden "pram" dinghy, its oars still in its rowlocks.

He and Simon carried this to the water's edge and, with Simon guiding him, my father rowed out towards a group of motor launches moored about 300 yards from the shore. While they did this my mother, Matthew and I waited on the beach, which was deserted except for a benign looking Labrador chained up by a fisherman's hut.

The dog's name tag said "Paddy" and Matthew and I stroked his ears while we anxiously waited for events to unfold.

Twenty minutes later we saw my father and Simon coming back. Hunched between them in the boat was a bedraggled looking, but familiar figure. "It's Harold Wilson," I said.

As my father rowed towards the quay, the Labour leader suddenly stood up, nearly swamping the boat. He then sat down again until it had docked, and Simon helped him onto dry land.

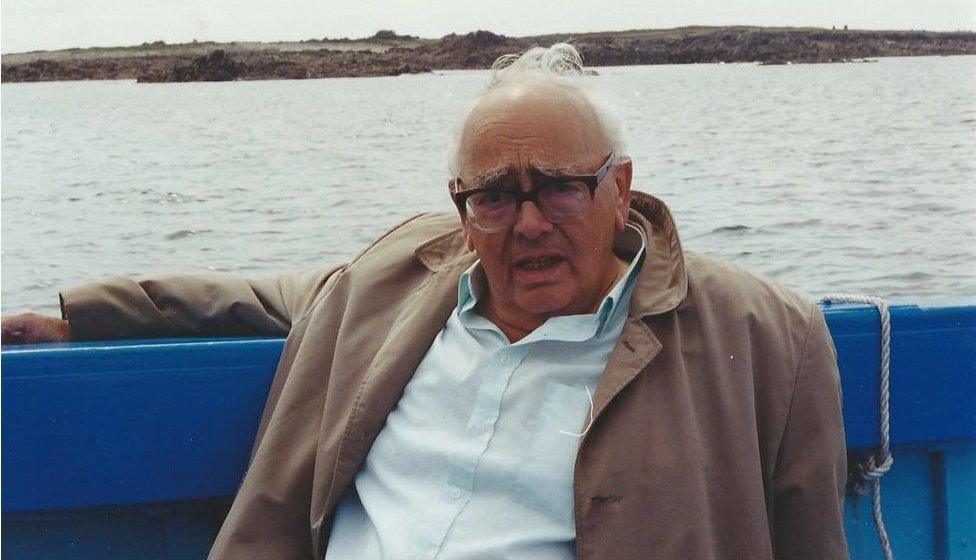

Paul Wolff in 1999

I vividly recall how shocked he looked. His shorts and shirt were drenched, his hair was plastered to his scalp, his teeth were chattering and his face was white.

He declined my father's offer of further help, including the loan of a bike to get back to his bungalow, but said that he was glad that we'd come along when we did.

My father jovially responded that it wasn't every day one pulled a former prime minister out of the water and that we were happy to have been able to help. Satisfied that Wilson was all right, we left him with Paddy and cycled away.

As we ate our picnic lunch my father and Simon explained that Wilson had slipped into the sea while attempting to step from his rubber dinghy onto his motor launch. The dinghy had shot away from him - the dinghy that we'd seen.

Unable to pull himself into the boat, Wilson had been left hanging on to the fender ropes for dear life. He'd told them that he'd been feeling sea-sick and that his arms felt "numb" and were "giving out".

Simon had stepped on to Wilson's boat and had then hauled the man on to the deck "like a sack of potatoes". Dad then swore us all to secrecy - if the story got out it could ruin the opposition leader's holiday, and our own.

The next morning we went down to Porthcressa and by chance we saw Wilson coming off the beach. I remember thinking that he'd be happy to see us again - perhaps he'd even ask us to tea? To my surprise I saw a flash of irritation cross his face.

My father greeted him and asked how he was. He replied that he felt all right, if rather stiff, and that he had spent the rest of the day in bed. "I've had my swim for the holiday though," he added pleasantly, then he went on his way and we didn't see him again.

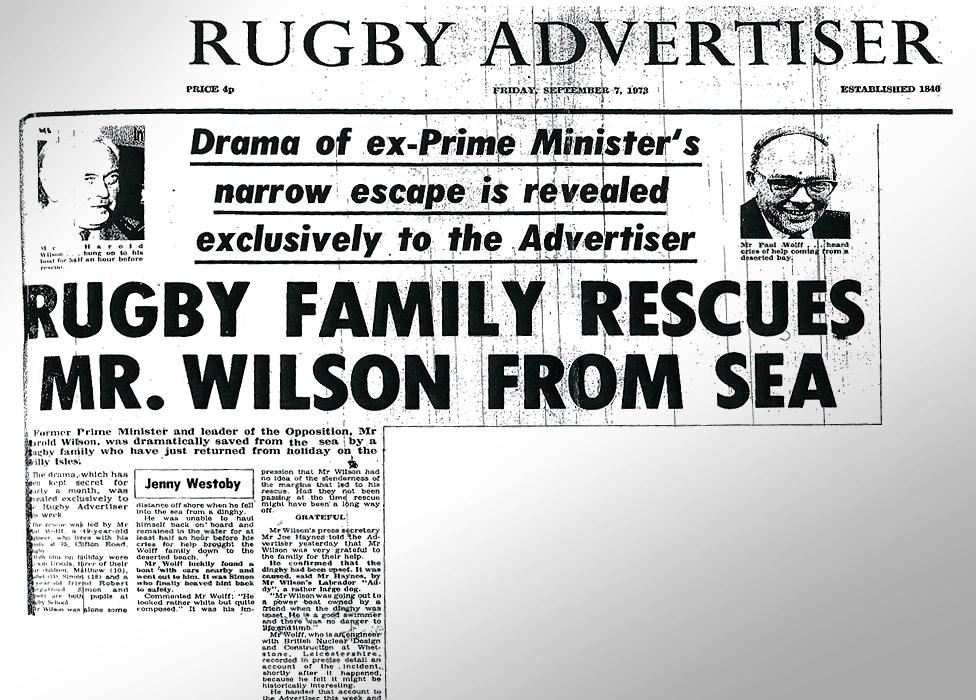

Returning home after the holiday we told no-one what had happened but somehow, a month later, the story got out. First my father was approached by our local paper which made the story a splash: "Rugby Family Rescues Mr. Wilson From Sea."

Was Paddy the culprit?

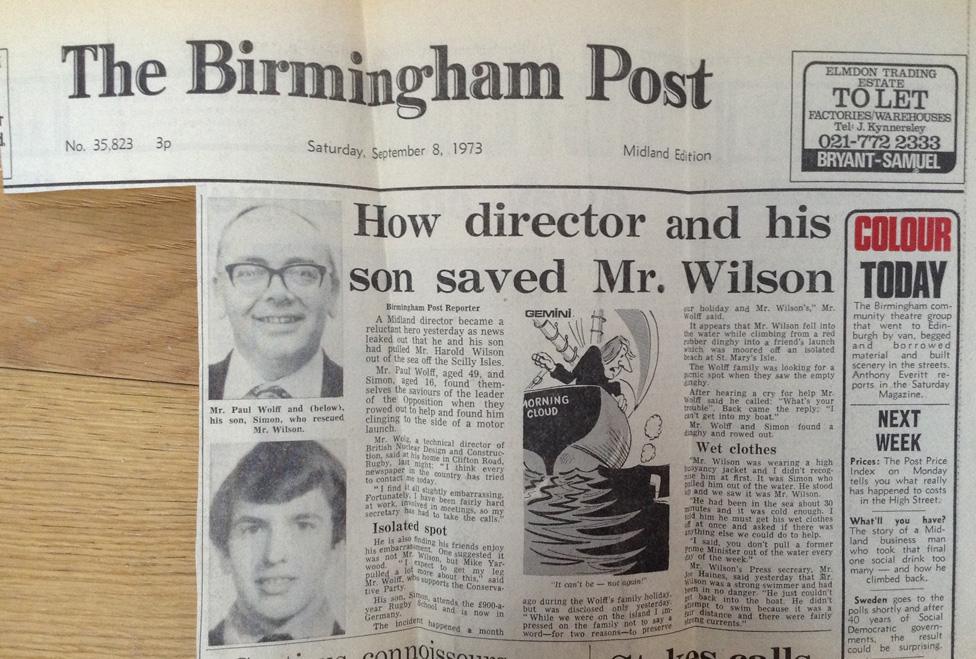

This got picked up by the Birmingham Post and within 48 hours my father's face was on the front of every national newspaper. Headlines such as "Wilson Snatched From Drowning" and "Wilson Rescued in Sea Drama" amused us, but we were outraged by the Daily Mirror's "My Dog Tipped me In!"

In a piece of Labour spin, Wilson's press secretary, Joe Haines, had apparently blamed the labrador. There was even a photo of "the culprit", Paddy, who was "in the doghouse".

One could see the need for damage limitation - the incident was extremely embarrassing for Wilson, not least because the Prime Minister Ted Heath was a world-class yachtsman. There were cartoons of Heath grinning at the news on board his yacht, Morning Cloud.

My father, a nuclear engineer, was besieged at work by TV film crews and quizzed about his voting habits. "Lifelong Tory Saves Wilson from Drowning", announced the Daily Telegraph. The Times pointed out that the Labour Leader, whose party had pledged to end private education, had been rescued by a public schoolboy.

And so it went on. We put up with myriad jokes of the "Why didn't you throw him back?" variety.

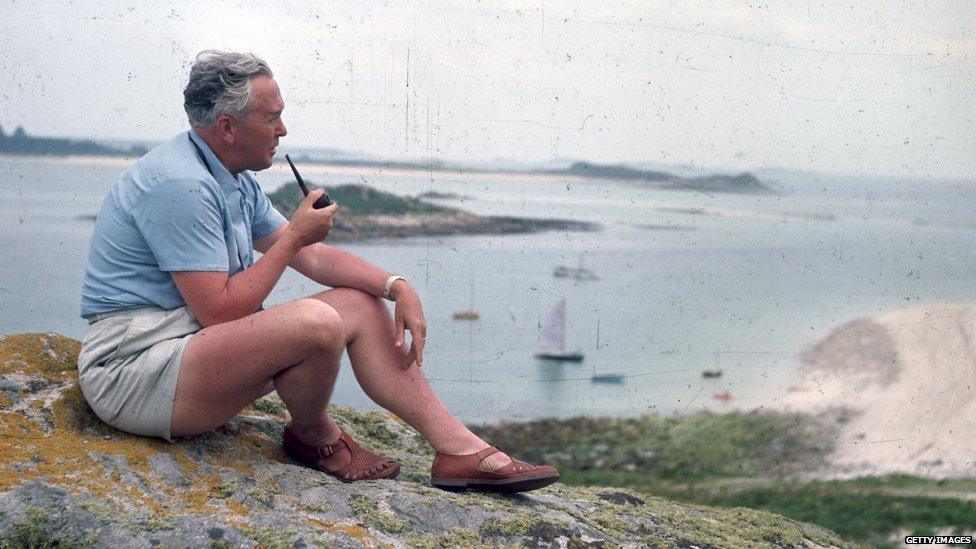

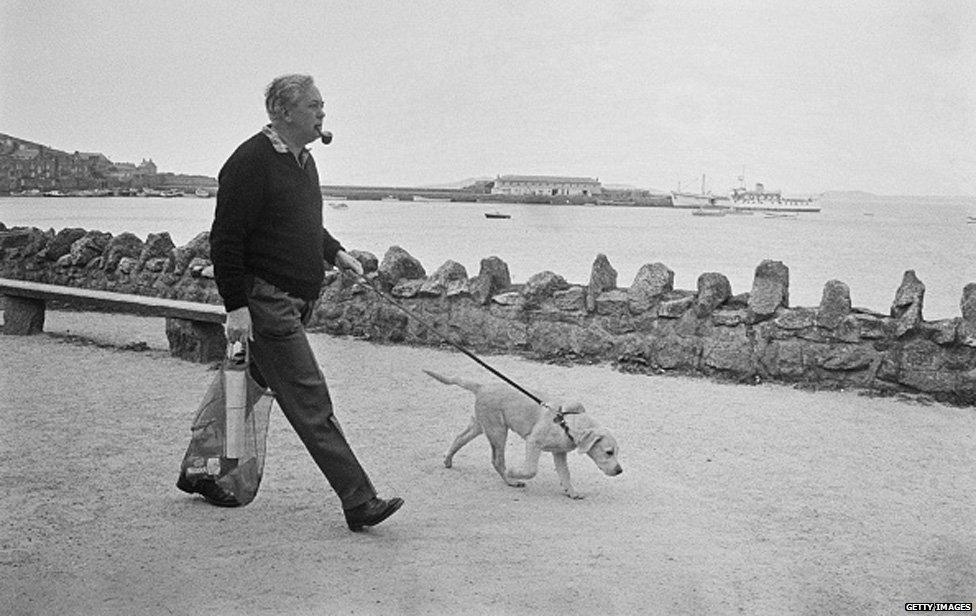

Wilson ties up up his boat on the Isles of Scilly

In the meantime Haines continued to elaborate on the story. Wilson, he claimed in the Mirror, was in "no danger". He "could have swum to the beach" but was "waiting for a friend".

The truth is, Harold Wilson would have died. Aged 57, he'd been in the cold water, never more than 15C on Scilly, for more than half an hour.

Knowing the strong Atlantic currents, he hadn't dared risk the long swim back to the beach. Worst of all, in that deserted spot, there had been no-one to hear his cries.

Reflecting on the incident afterwards, my father told us that Wilson seemed not to understand that it was "only by the slenderest margins" that his life had been saved.

Six months later, in February 1974, Harold Wilson became prime minister again.

It's now 42 years since "The Wilson Affair" as my family always called it. It seems strange that despite all the publicity this very significant event in the life of Wilson is almost unknown.

Neither of his official biographers, Ben Pimlott and Philip Ziegler, mentioned it in their respective books, nor did Joe Haines revisit it in his own memoir of Wilson, Glimmers of Twilight.

I sometimes wondered how Wilson's colleagues had viewed the story at the time. Were they sympathetic? Amused? Did they pull his leg about it?

"Oh I remember it well," Denis Healey told me when I phoned him in the House of Lords a few months ago. "Harold seemed very embarrassed by it and was clearly anxious to play the whole thing down. We didn't feel that we could mention it to him - definitely not."

And if my family hadn't happened to pass by when we did? It's fair to say that the course of British politics might have been rather different.

Denis Healey or Jim Callaghan might have succeeded Wilson. Edward Heath might not have been defeated in 1974 and there might well have been no Tory leadership challenge the following year and therefore, quite possibly, no Thatcher premiership.

My late brother, Simon, used to wonder whether our father may, on that fateful August day, have inadvertently launched Margaret Thatcher's prime ministerial career.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Isabel Wolff is author of Ghostwritten

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox