Silenced - the day my daughter was shot in front of me

- Published

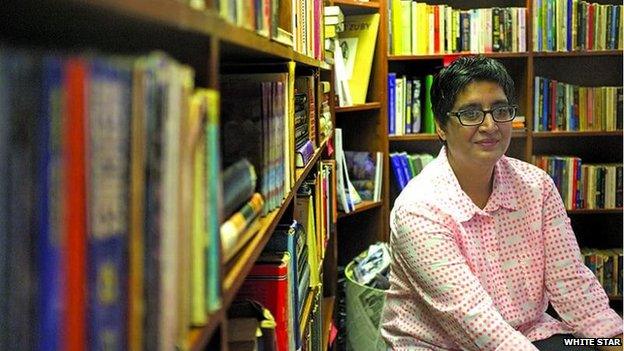

Sabeen Mahmud was a passionate supporter of free speech. She ran a space in a Karachi cafe for people to talk freely about politics, society and human rights - but six weeks ago, in the latest of a string of attacks on liberal activists in Pakistan, a gunman killed her as she drove home. Her mother, Mahenaz, who was next to her, talks about her remarkable daughter.

I hadn't visited the space for quite a while but that day I just wanted to be around her - it was just a feeling, "I have to go today, and I have to be around, just to show her my support."

This image keeps going round all the time in my head - these eyes looking, and this gun coming out. I said to Sabeen, "Just look, I mean these guys, what do they want?" I thought it was a mugging actually, I thought they wanted a handbag or phone, because that's pretty common in Karachi. But then I heard the gun shots, the glass shattered and Sabeen was gone and they disappeared.

I took two bullets. One bullet actually is one of the bullets that Sabeen took, because they fired at such close range - we were stationary because we were at a traffic signal which was red. There were people all around us, and this motorcycle rode up a bit too close for comfort at Sabeen's side and they fired from there and one of the bullets went through her, out and into my arm and out of my arm. That is one. She took five.

The other one, the police believe it came in and ricocheted somewhere in the car and it went into my back. I must have moved forward to look at her. I was saying to her, "Sabeen, can you hear me? Say something, we'll just get you to the hospital."

Sabeen's sandals in the footwell of her car, surrounded by shattered glass

We did have a part-time driver who was sitting in the back, so then he moved to the front seat and he rushed us to the hospital which was close by.

They gave me some first aid and then I was told I was going to another hospital and they took Sabeen somewhere else. She had to be taken to the morgue actually and I was taken to another, bigger hospital.

Loads of people came, because almost instantly our TV channels had picked up the news, and whoever saw it was on social media telling someone else.

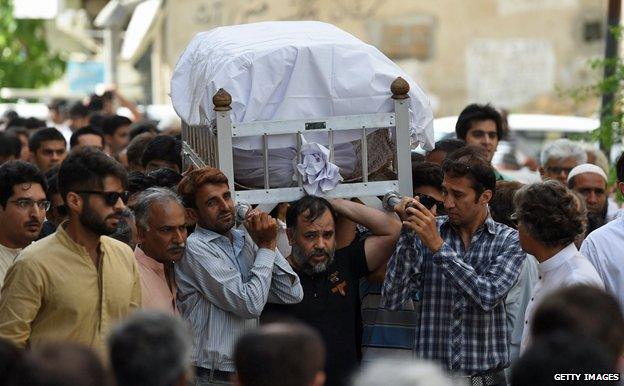

After she died, there was a huge outpouring of support on social media. I have no idea how many people came to the funeral but I was told there were more than 2,000 people. I don't know how many people I hugged that day.

I'm a bit overwhelmed by all the people who came. I still can't fathom it, because to me, she wasn't this public person, she was my family, she was part of me. She was my daughter, and who are all these people mourning her now? It's a bit awe-inspiring, it's overwhelming, I can't fathom it.

I think I'll have to tell you a little about myself in order to understand my own child-rearing practices.

I was born in India, in Kolkata, and when I was five we moved to Dhaka which was then East Pakistan but which is now Bangladesh. I had quite a privileged childhood, we had lots of domestic help at home. I was raised by a nanny whom I really loved. She was Catholic, she would take me to church every Sunday because my parents would be asleep.

In Kolkata and in Dhaka we mixed with people from all different religions and everything was acceptable. So I raised Sabeen very much as a global citizen and I used to say to her, "Look, everybody's good, there's nobody who's not. Just because of a country they may belong to, or a race or a religion, it really doesn't matter. It's people who matter. No matter if somebody's poor or rich, we're all equal and we have to be respectful and mindful and count our blessings." She internalised all of those values - and she saw me live that life, it wasn't just rhetoric.

Demonstrators in several cities protested against Sabeen's killing

Her idea of fairness started when she was very little. In fact the headmistress of her kindergarten said Sabeen came to the office one day and complained, "The teachers are really unfair - why is it that only boys can play the big drum? Why can't girls also have a go at it?" When she went to senior school, it was, "Why is it that girls can't be in the cricket team? Why is it that we can only play softball?"

I pretty much believed that she should be left on her own and she should do whatever she wanted to do. She always did these very risky things that most normal parents would not allow their daughters to do, no matter how independent or old they might be - she was 40. But I always said, "Follow your heart, follow your dream, do what it is that you have to do, no one should get in the way of that."

I became a single mum after Sabeen had grown up, she was about 19 - she's the one who initiated my divorce, strange as it may sound. She came back from college in Lahore and said, "Look, if you're staying in this marriage for me, please don't do it." And then she went off and found out from lawyers what the process could be to have a separation, and took me to a legal aid person and we talked about it and then she got all the paperwork done and went to her dad and got him to sign.

She was a very unusual person.

What we hear now is "human rights activist" and "arts patron" and I think: No. She was not really an activist in that sense, it was just her huge sense of fairness and justice. If she felt something was wrong she couldn't sit still, she just had to raise her voice. So she didn't have just one cause. She would fight for any and everything - for individuals' rights.

In recent years lots of young people who were not able to express themselves would come to her because their parents didn't understand them, and she would counsel them. She would take off sometimes at three o'clock in the morning to sit with minority groups who were being oppressed, just to show her solidarity.

Over the last few years I said to her many times, "Sabeen, one of these days you're going to get a bullet in your back. But no worries, don't let that stop you from doing what you want, I will have to deal with whatever happens."

So that's what's happening right now - I'm having to deal with it.

Mahenaz Mahmud spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service. Listen to the interview on iPlayer

She had received some warnings and some threats. She knew that this event she was hosting [on the day she died] was a risky one - the event was called Unsilencing Balochistan. This is a place where activists have been missing for a long time and families have been obviously shattered - and it's not talked about.

There was supposed to be a talk at Lahore University of Management Sciences, which is quite progressive, and then they cancelled at the last minute. Somebody called her and asked her if they could have the event at her space and she agreed. Sabeen felt, "This has to be said, this is not right."

I'm grateful for the fact that I was there with her that day, right next to her in the driver's seat, and know that she died instantly. The police say it took about four seconds. There was not a whimper, not a moan, not a groan, not a frown - nothing.

She didn't suffer and there was no horror on her face, she was very peaceful, and she had her dignity even in death in that she didn't slump over, just her head tilted a little - and that was it.

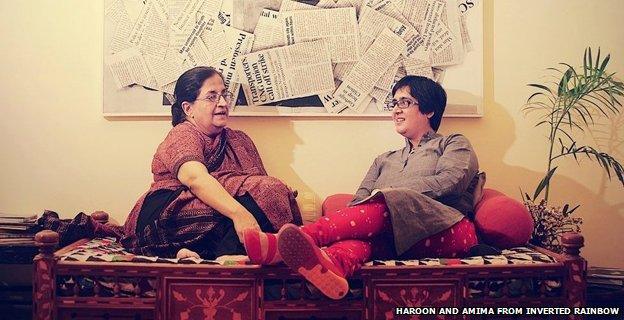

Mahenaz by the "Wall of heartbroken lovers" - part of the Dil Phaink exhibition in London that Sabeen was working on

Of course I realise that my grieving will go on for the rest of my life, but where she's concerned, my solace is that she lived a very meaningful, purposeful, mindful life. She did more than most people would do in this short lifespan. And she's in a safe place now.

My strategy was, "OK, don't think about it now, think about it tomorrow." Shall I tell you where that came from? When I was about 17 I read Gone With The Wind, and in that, when everything is devastated, the way Scarlett O'Hara dealt with it was - I'll think about it tomorrow.

Somehow that stayed with me, and in 1969-70, my home was in Dhaka and it was slowly disintegrating - friends were leaving, migrating, and each time I felt a little bit of me was going away. The lanes and the homes that we celebrated in, loved in and had fun in, were gradually dimming. Then one fine day war broke out and we lost that part of the country and suddenly in the blink of an eye home was no longer home. It was a very difficult period in my life, and that's how I coped with that.

I'll think about it tomorrow because I keep telling myself, "It's a lifetime of missing her. Don't start now, think about it tomorrow."

I also have a bit of a fear of different causes appropriating Sabeen - and I don't see her as an icon for any one cause. I don't want her to be put in any one box, to be categorised as a human rights activist, I don't quite see her like that - she was very much a whole person.

I want her to be remembered as a human being who cared very deeply for people who were oppressed or people who couldn't speak up - for freedom of expression. Somebody who was lively, intelligent, fun and very caring. She talked a lot about love. I think Sabeen defies definition.

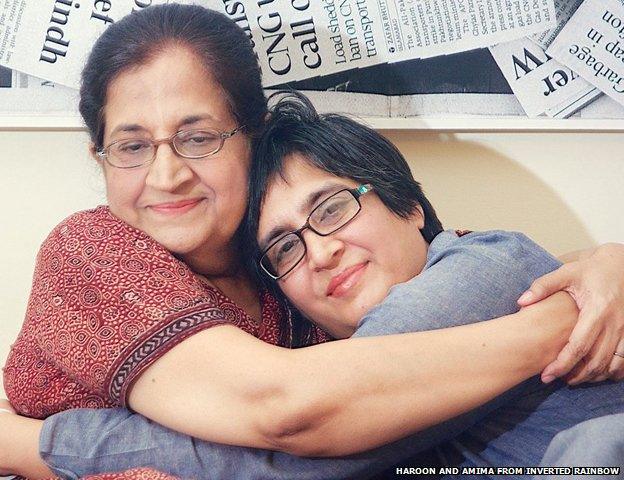

Mother and daughter

Sabeen Mahmud was the director of Peace Niche, an NGO which promotes free speech through culture.

Its best-known venture is T2F (The Second Floor) a cafe in Karachi which has hosted hundreds of events including concerts, film screenings and science talks. T2F was named after its first home in a second-floor rented office.

In 2013, Sabeen campaigned in support of Valentine's Day, which religious fundamentalists had condemned as decadent. She printed posters that said, "Don't keep your distance, let love happen." She had to go into hiding.

Sabeen had been working on an art exhibition at London's Southbank Centre - Dil Phaink, external, which means "Throw your heart out there in the world," opened three weeks after her death. Mahenaz, who still has a bullet in her back, attended the opening.

Mahenaz Mahmud, 64, has been described as a "guru" of Early Childhood Education, and helped develop Pakistan's first early years curriculum. She has run educational projects in slums and rural areas, and still trains teachers.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published24 April 2015