The WW2 soldiers France has forgotten

- Published

The fall of France 75 years ago is conventionally seen as a moment of abject national disgrace. But today some insist the French military has been wronged - and that the hundreds of thousands of French troops who fought in the Battle of France deserve to be honoured, rather than forgotten.

It all took less than a month. Faced by the onslaught of Hitler's tank divisions - the notorious Panzers - the French army collapsed and Prime Minister Philippe Petain capitulated.

"After the war, as we all know, de Gaulle wanted to wipe out the memory of the debacle," says historian Dominique Lormier, author of several books on the period.

"So the focus was on the Resistance and on the Army of Africa, which fought the Germans from 1944. The sacrifice of the soldiers who fought in 1940 was forgotten."

Lormier is one of a number of historians who are reinterpreting the events of May-June 1940, using French and German military archives. And the picture they paint is not the Nazi walkover that has commonly been represented.

Five million men were mobilised in France at the start of World War Two. The army was reputed to be one of the strongest in the world, certainly every bit a match for the Germans.

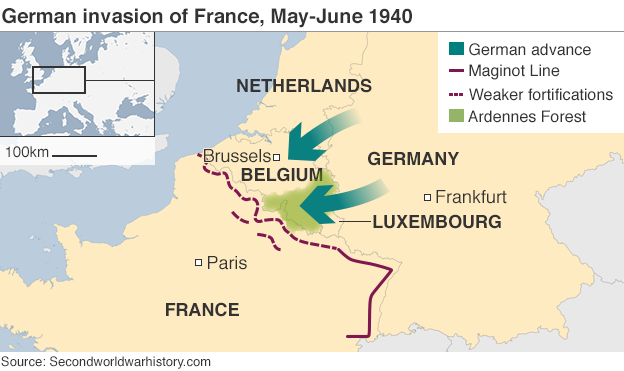

Along the eastern frontier ran the supposedly impregnable Maginot Line, a series of more than 50 ultra-secure fortresses.

The Maginot Line - designed to be an impregnable defence, but the Germans bypassed it

And if the Germans decided to invade from the north - as they did in World War One - then there were plans for a counter-thrust to block them inside Belgium. The British Expeditionary Force was there to help.

The problem was that Hitler defied the military theorists by sending his Panzers through the wooded Ardennes hills, at the corner of France's northern and eastern fronts. No-one expected this because everyone assumed the roads there were impassable. But it worked.

Until recently, most historians have focused on the evident shortcomings of the French armed forces.

Unarguably, French commanders made terrible strategic errors. They put their best forces into Belgium against the German feint, and were dangerously exposed along the vital river Meuse at Sedan (which the German tanks had to cross after penetrating the Ardennes).

The French air force was large in size, but most of its planes were out of date. And on the ground the concept of modern tank warfare - the concentrated armoured thrusts made by Rommel and Guderian - had yet to be accepted by a French command that was still obsessed with infantry.

In his classic To Lose a Battle: France 1940, British historian Alistair Horne also makes much of the collapse of morale among the French.

12 June 1940: Refugees fleeing during the German aerial bombardment of Dunkirk

Like many writers, he says the memory of 1914-18 still haunted the French leadership which meant there was little appetite for a fight; while the bitter ideological divisions of the 1930s - with far-left and far-right at times battling on the streets of Paris - had sapped the patriotic spirit.

But for Dominique Lormier and others of the revisionist school the truth is more nuanced.

"Morale was not nearly as low as Horne says. People have forgotten that in many places the French fought hard and bravely and put the Germans in real difficulty," he says.

"The figures speak for themselves. Of the 3,000 tanks the Germans deployed, 1,800 were put out of action. Of 3,500 planes they lost 1,600. In a month of fighting they lost 50,000 dead and more than 160,000 wounded. It was a genuine combat."

One example is the Battle of Hannut, which actually took place in Belgium. Here the French Somua tanks, though outnumbered, proved every bit as powerful as the Panzers, Lormier says. The result, in his view, was a tactical victory for the French.

French Char D2 tank, 1940

Other memorable moments in an otherwise depressing litany of defeats were Gen de Gaulle's tank charge at Moncornet and the battle of Stonne - a village near Sedan which changed hands nearly 20 times over days of bitter fighting.

The French also capably covered the British retreat to Dunkirk, says Lormier, with the result that far more men were successfully evacuated than had been feared.

In addition, there was also tough fighting against the Italians in the Alps, while on the Maginot Line only a handful of forts had capitulated by the armistice in mid-June.

But the greatest injustice - for many - is not the failure to commemorate these minor victories, but the slur over the years on the courage of individual French soldiers and airmen.

10 May - German forces advance into Holland and Belgium

11 May - German Panzer forces break through Allied defences at Sedan, effectively bypassing the Maginot Line

13 May - Germans cross River Meuse into France

20 May - Gen Guderian's tanks reach Abbeville, cutting off Allied forces in Belgium

9 June - Tanks led by Rommel cross the Seine

16 June - French PM Paul Reynaud resigns; new government formed by Marshal Philippe Petain

22 June - Franco-German armistice signed; northern France occupied, the south-east to remain under control of Petain's government in Vichy

Philippe de Laubier, now in his 80s, has only vague memories of his father - an air force group commander called Dieudonne de Laubier. But the story of his death in May 1940 still inspires him.

"My father was flying these ancient bombers called Amiots. They were hopelessly old-fashioned.

"When the Germans put their pontoon over the river Meuse at Sedan, it was vital to throw everything at them. My father had just flown a mission and he was not supposed to go up again.

"But the thought of his squadron flying into such danger without him was unacceptable. So he stopped one of the Amiots as it was taxiing on the runway, and ordered one of the men off so he could take his place.

"Of course they were quickly shot down by German flak and my father was killed."

The idea that the French military lacked fighting spirit is to him both misplaced and offensive.

For Dominique Lormier, proof of the grit of the French soldiers is to be found in the German army day logs - where commanders described the progress of the battle.

He quotes Gen Heinz Guderian as writing: "Despite the major tactical errors of the Allied command, the soldiers put up an obstinate resistance with a spirit of sacrifice worthy of the poilus (French troops) of 1916."

Rommel, meanwhile, wrote: "The (French) colonial troops fought with extraordinary determination. The anti-tank teams and tank crews performed with courage and caused serious losses."

Hitler and his lieutenants in Paris following the French surrender

Of course it is debatable how much credit should be given to give such statements. Commanders conventionally honour their opponents, if only to make their own victories appear the more impressive.

And at the end of the day, the fact remains that the French army did collapse. On 17 June, Marshal Philippe Petain gave an infamous broadcast calling on troops to stop fighting (even though an armistice had yet to be agreed), triggering mass surrender.

But today many feel not enough has been done to remember the "First Resistants".

"These soldiers have been doubly punished. Not only did they lose their lives in the Battle of France, but then they lost the battle of our memories," says Charles de Laubier - Dieudonne's grandson and a journalist.

In Le Monde newspaper, Charles has written a call for a national day of commemoration, external to honour the estimated 90,000 French dead in the Battle of France. Today there is no physical memorial for the men, and their story is rarely told.

"It is a denial of memory that verges on the taboo," he says. "It is time to bring it to a close."

More from the Magazine

Sections of Hitler's Atlantic Wall are being restored by French enthusiasts. But should the Nazi fortification be fully embraced as part of the country's heritage?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.