The secret US mission to heal Saudi King Ibn Saud

- Published

Six decades ago, the US and Saudi Arabia had an uneasy relationship based on oil and regional security, but a secret trip by President Truman's personal physician to treat the Saudi monarch drew them closer together.

In February 1950, the US ambassador in Saudi Arabia sent an unlikely and unusual request to the State Department.

"HM has request our assistance in obtaining the immediate services of an outstanding specialist, who with an assistant could go to Saudi Arabia to examine and treat him for chronic osteoarthritis from which he is becoming increasingly uncomfortable and enfeebled."

"HM" was the King of Saudi Arabia, Abdulaziz bin Abd al-Rahman al-Saud, commonly known in the West as Ibn Saud.

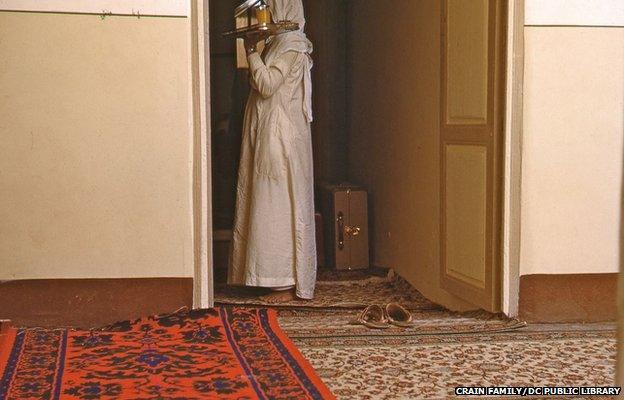

The mission was put up in Riyadh at the newly completed guest palace for the King of Afghanistan

The request came at a complicated time for US-Saudi relations. The US was leasing the Dhahran airfield, but many Saudis, including the more conservative religious authorities were increasingly against any American military presence.

Ibn Saud himself was still wary of America's recognition of Israel. And there were ongoing negotiations over how the profits from Aramco, a oil firm jointly owned by Saudi Arabia and American companies, should be split.

King Ibn Saud was powerful and savvy leader who had unified the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, but he was ageing, and the pain and swelling in his legs from arthritis had limited him largely to a wheelchair. When the Americans did see him, one said when he walked, those nearby could hear his bones grinding.

A State Department memo by Saudi expert Fred Awalt noted the king's own physicians had done well by Ibn Saud and "could have done better had the latter accepted their recommendations and treatment".

An earlier successful trip by an Air Force doctor to treat Crown Prince Saud for an eye issue may have convinced the monarch to look elsewhere for relief.

The defence department sent two specialists and former military men, as well as equipment technicians. But Truman added his personal physician, Brigadier General Wallace H Graham, to the trip.

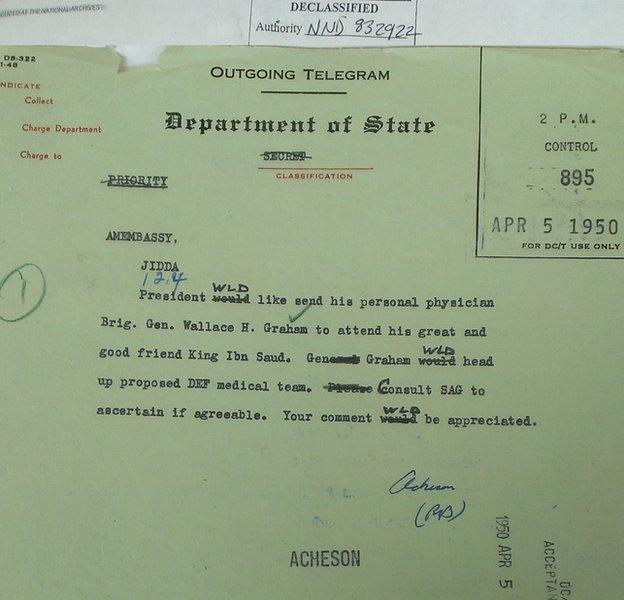

Secretary of State Dean Acheson told the US embassy in Jeddah the president wanted Gen Graham to "attend his great and good friend" and head up the defence medical team in a then-secret telegram, now on file at the US National Archives.

Childs replied that he felt Ibn Saud would be "greatly touched" by President Truman's offer and said it would go far "in convincing him of our genuinely friendly sentiments".

The mission took off from Washington on 15 April 1950. It was small and secret.

As the preparations were being finalised, the Saudi government sent an emergency telegram to their ambassador in Washington to ask the Truman "not to permit any news either press or radio concerning medical team coming here".

The Saudis feared the suddenness of the trip would fuel rumours Ibn Saud was seriously sick and considering abdicating. He had no interest in stepping down.

But Mr Truman would have had his reasons to keep the special mission quiet as well. Saudi Arabia was an unlikely but important potential ally - because of the connection with Aramco's oil and the government's staunch anti-communist feelings. But such an alliance would not be popular back in the US.

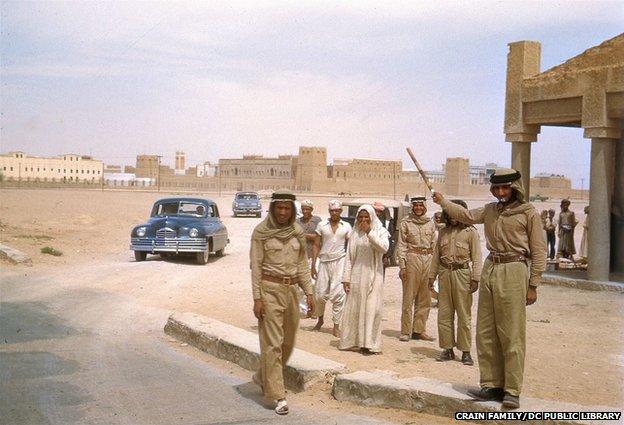

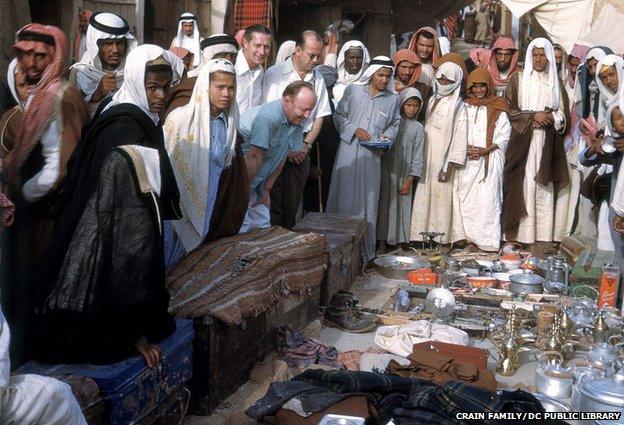

US visitors dining in Riyadh

The two specialists on the defence team were former military members - Dr Gilbert Marquardt and Dr Darrell Crain. Dr Crain was a Washington, DC resident who brought his hobby - photography - along with him to Saudi Arabia.

Dr Crain's granddaughter, Alice Makl, found the photos - along with many others - in storage last year.

After a three-day journey, the party arrived in Saudi Arabia and was met by the king, who according to Heyward Hill, a counsellor at the US embassy, "was impatiently and excitedly looking forward to the coming for these physicians".

Despite his credentials as a doctor, Gen Graham's presence on the trip was also a diplomatic sweetener - something he suggested himself in the first meeting with ibn Saud.

"Gen Graham smilingly added that President Truman was 'sending him as a gift to the King'," Hill wrote in a memo sent back to Washington.

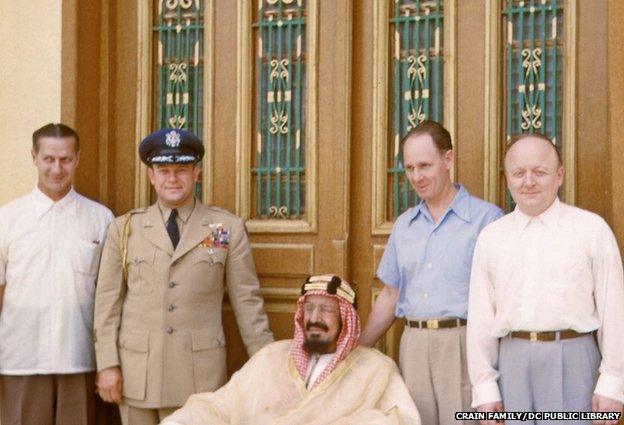

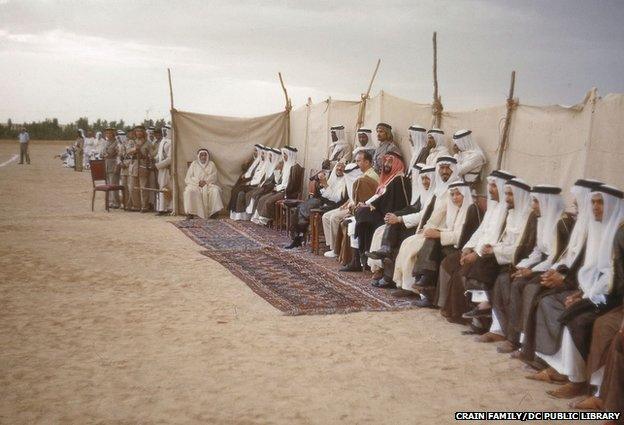

Gen Wallace Graham (centre-right) was a gifted diplomat himself

Dr Darrell Crain (left) joined Gen Graham on the mission

"His majesty laughed and said it was a very precious gift indeed."

But Gen Graham was an effective diplomat himself, speaking highly of the King's own physicians, calling them "first-class men" and noted his team could mostly be helpful by bringing the "very latest developments in medicines and equipment".

In 1989, Gen Graham told an oral historian that Ibn Saud's pain was severe.

"He had free loose bones in the knee joints and he had loose, hard, cartilage and broken-off pieces of bone in there," he said. He pushed for Ibn Saud to come to the US for surgery, but the king refused.

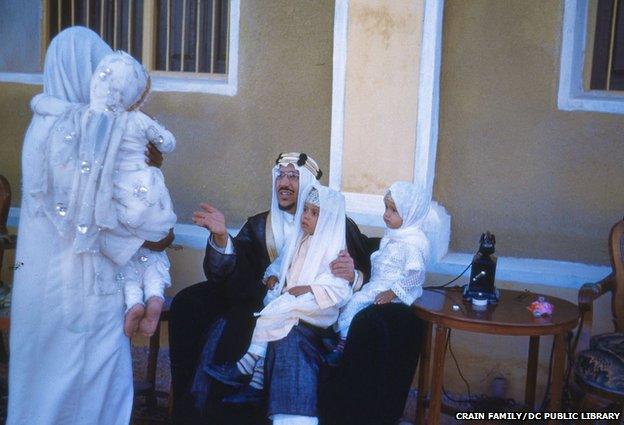

Crown Prince Saud bin Abdulaziz (later King Saud) in 1950

A servant in the residential palace

Dr Crain's own log shows almost a dozen treatments over several days.

Alice Makl says the experience humanised a powerful king for her grandfather. Dr Crain had spent a career trying to alleviate people's pain, and Ibn Saud was no different.

Ibn Saud's arthritis had limited his travel and responsibilities

"Here's a man who was very proud and had a successful history," she said, but he was also "a guy getting old who was in a lot of pain".

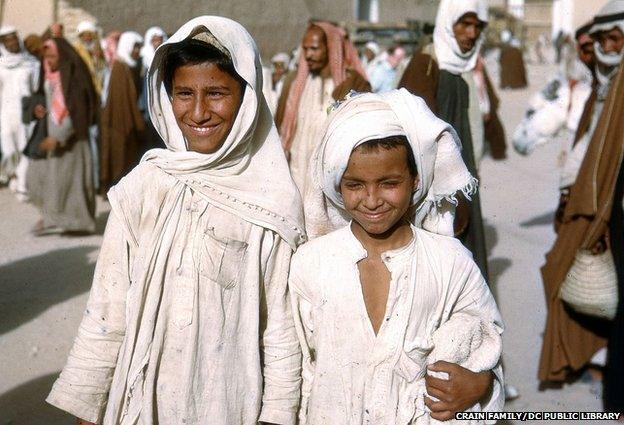

The journey also provided information to the State Department about life for everyday Saudis.

"It was noted with considerable interest that many of the old restrictions on music, games, toys and other forms of non-religious pastimes have been lifted in Saudi Arabia," Awalt wrote in his memo, crediting Crown Prince Saud for most of this change.

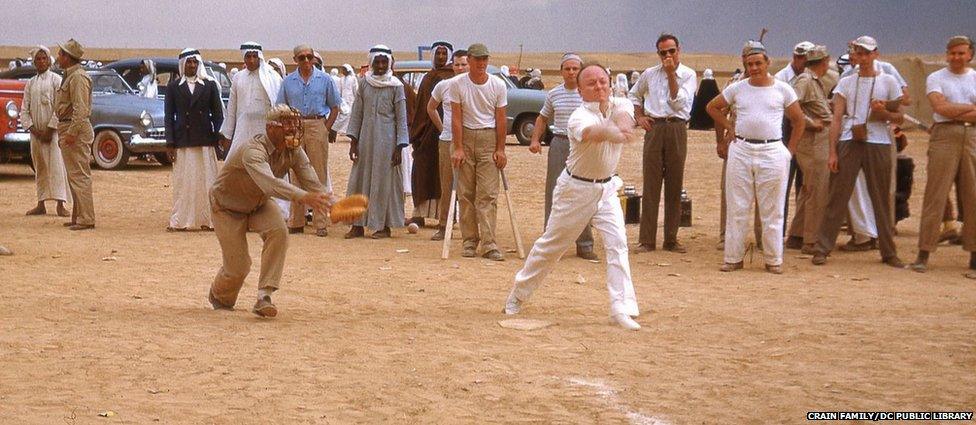

During their visit, the crown prince held a baseball game - the visiting physicians versus Americans working for Bechtel in the country - as well as a football match against the local Saudi team.

The Saudis won 6-0 at football.

While he refused surgery, the treatment relieved some of Ibn Saud's pain - to the point he began taking back on responsibilities in the kingdom previously assigned to his son.

Awalt reported in a telegram in May the Saudi monarch had gone from constantly using a wheelchair to moving about with "considerable ease and with his knees fully straightened".

And Ambassador Childs reported back to Secretary of State Acheson that the mission had created a "great amount good will".

The trip bound US and Saudi closer together. In August the following year, Ibn Saud fell sick again with "severe pains and convulsions in the lower abdomen".

In a memo to the president, Mr Acheson "strongly recommends" Gen Graham and other doctor make the trip to Saudi Arabia immediately.

Sending Gen Graham, Dean Acheson said, was not only "deeply appreciated" by Ibn Saud "but also a diplomatic stroke which paved the way for the recent signature of an extremely favourable United States-Saudi Arabia agreement".

The mutual defence agreement is the basis of military co-operation between the two countries that continues today - despite periods of strain.

President Truman approved the mission.

As Gen Graham, Mr Awalt and several medical specialists met at the White House in 1951 days before departure, President Truman stopped in and made a telling remark about how important Ibn Saud - and Saudi Arabia - had become to the US.

"The president told the group that they were going on an important mission to a great man," Mr Awalt wrote.

"'He is our friend,' he said."