The place where wolves could soon return

- Published

The last wolf in the UK was shot centuries ago, but now a "rewilding" process could see them return to Scotland. Adam Weymouth hiked across the Scottish Highlands in the footsteps of this lost species.

In Glen Feshie there stand Scots Pines more than 300 years old, and in their youth they may have been marked by wolves. It is beguiling to think that now, camped beneath them, boiling up water for morning coffee.

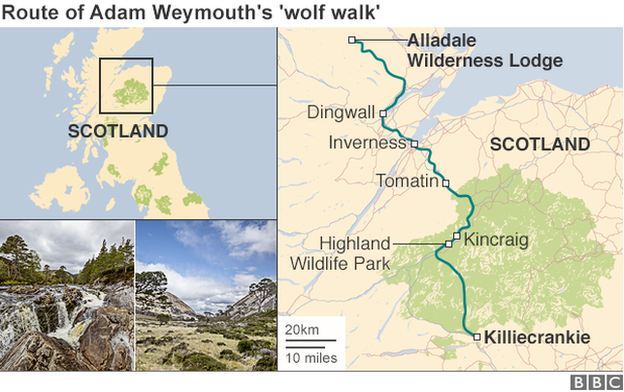

Last year I walked 200 miles across the Highlands to see how those that lived there would feel about the reintroduction of the wolf. The wolf's population has quadrupled in Europe since 1970, and the fact that they remain extinct in Britain is increasingly anomalous.

With the return of the beaver, the success of the wild cat, a growing call for the return of the lynx, as well as an EU directive obliging governments to consider the reintroduction of extinct species, could it be time for the wolf's return? David Attenborough thinks so, external. Yet 250 years since their eradication, the animal is still capable of inciting powerful feelings.

I wanted to see how those who would live among them would feel about having them back, and for three weeks I followed moors and bogs and ancient footpaths, passing the site where the last wolf in Scotland was killed, and the glen where some hope that the first wolf could come back.

I began my walk on the Alladale Estate in Sutherland. At 28,000 acres, it comprises two valleys, Glen Alladale and Glen Mor. From the summit of the highest peak, Meall nam Fuaran, at 674m (2211ft), you can see the sea both ways. Paul Lister purchased the land in 2003.

In jeans and patched jumper, he seizes hold of my hand and ushers me through to the lounge. On the walls there are black and white etchings of hounds and hunting scenes, the light fittings modelled from antlers.

Lister is heir to the MFI fortune. His father was not only instrumental in funding the purchase of Alladale, but he inspired it as well. "About 13, 14 years ago, my dad got very ill and I spent 10 weeks with him in intensive care," he says. "I had an epiphany after that. I stopped working and bought a Highland estate that I could start to restore."

We head out in the Land Rover to see some of the estate, bouncing along the rutted tracks. He points out the bright green swathes on the valley sides that are the newly planted saplings - 800,000 of them since he took over the land.

The peatlands are being rewetted, returning them to functioning carbon sinks, removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Moose and wild boar have been tried, and there is a wild cat breeding programme.

But Lister has greater ambitions. That evening, as I sit looking out over the wide and empty space, watching the sun going down, I try to imagine wolves here. It is not so hard to do.

When he announced in 2007 that he intended to fence in Alladale and reintroduce two wolf packs, he generated the sort of media furore that most campaigns can only dream of. There was a six-part BBC documentary - headlines called him the wolf man, and howling mad. But Lister is clear in his vision.

"It's carnivores that are needed to manage deer numbers," he says. "Trees aren't out of control in Scotland. Deer are."

Red deer numbers have doubled in Scotland since 1965, and as I left Alladale I drove before me, for several hours, a herd of two or three hundred of them. The track traced the bank of the Diebidale as it wound up through Glen Calvie.

Grouse gave themselves away, diving forth from the heather with a cackle, and once I saw a ptarmigan, motionless, camouflaged almost to perfection. I ate a lunch of venison leftovers in an abandoned cottage high up on Carn Chuinneag, sheltering behind a ruined wall, out of the buffeting wind.

By the time I came to the high and open moor, the sky had greyed and the rain was blowing, fine but horizontal and continuous. The crags of Carn Loch nan Amhaichean blurred and vanished.

I tried to hold a path south through the bog, and leapt from one peat hag to the next, descending into crevasses with ground above my head, the runnels of water black and viscous, reflective as oil slicks. Glints of colour, purple saxifrage, sphagnum moss, the reddening leaves of the bilberry.

Pulling myself up by handfuls of heather as my boots slipped and mired, while occasionally, emerging from the peat, preserved, a piece of fossilised Caledonian pine. Many of these pieces have been carbon dated at roughly 4,000 years old. Yet now, except for some areas of plantation, distant, hung with mist, there was scarcely a tree to be seen.

There is debate as to the extent that the forests of Caledonia once stretched. While both climatic and human factors contributed to their demise, it is deer that are preventing their return. Each tree I saw as I walked south was memorable for its scarcity, a single birch on a rocky outcrop, a clutch of rowan on an island in the river, each in some inaccessible spot where it had been protected from the nibbling.

A similar problem, caused by elk, was the reason behind the reintroduction of the wolf into Yellowstone National Park in 1995. How Wolves Change Rivers, external, narrated by journalist George Monbiot, was one of the more unlikely videos to go viral last year, now watched by more than 20 million people. Bringing back the wolf to Yellowstone, he claims, not only reduced elk numbers, but it kept them skittish and on the move, allowing for further regrowth of the trees.

The birds moved back in, and the beavers. Their dams created habitat for other creatures, and as the roots of the trees shored up the banks, the rivers became less sinuous, forming in slower flowing pools that attracted still more wildlife.

"The wolves," said Monbiot, "changed the behaviour of the rivers." It has the perfect narrative arc - the evil wolf redeemed.

Yet David Mech, a biologist who has worked extensively in Yellowstone, advises that such simple narrative arcs are hard to find in something as messy as an ecosystem. Mech does not discount all of Monbiot's claims, but cautions that as much harm could come to the wolf from being marketed as the poster boy of the environmental movement as it did in the era when it was hated and feared.

"We as scientists and conservationists who deal with such a controversial species as the wolf have a special obligation to qualify our conclusions and minimise our rhetoric," he says, "knowing full well that the popular media and the internet eagerly await a chance to hype our findings. An inaccurate public image of the wolf will only do a disservice to the animal and to those charged with managing it."

This is the problem of the wolf. Three hundred years might be a blink in biological time, but no one can be certain what effects a new top predator would have, and polarised opinions make rational debate difficult. As such, Lister's plan to try out the animal in an enclosure, as beavers were established at Knapdale, external, are seen as a positive step by some, but others are scathing of his plans.

The Ramblers (formerly the Ramblers' Association) support reintroductions, Helen Todd says, but see Alladale as "a rich man's dream". She is worried about the precedent Alladale could set - if wolves justify fencing in land, they could become the guard dogs of the very rich, allowing estate owners to subvert the Right to Roam.

"He wants to keep everybody out of the fence unless they pay money to go and see them," says Todd. "That's not really what we have in mind when we think of reintroduction."

Lister doesn't accept that view. "My problem is I want to put some wildness back into a small area of the Scottish Highlands, and I want to get on with it. I think nature and wildlife take precedence. We've done enough to the landscape over the last millennia to want to be able to put something back."

"People are part of the landscape too," says Todd. "People did use to live there. I'm not sure what model we'd use to bring people back, but certainly you can't have sustainable development if you don't take account of people as well."

Local MSP Robert Gibson sees people, not wolves, as "the most endangered species of all" in his constituency, as the young move south for education and employment. "This is a Clearances landscape," he says, referring to the eviction of tenants to make way for sheep in the 18th and 19th Centuries, resulting in Scotland having one of the highest concentrations of land ownership in the world.

Three-quarters of Sutherland's 5,200 square kilometres are in the hands of just 81 families, with one person employed for every seven square kilometres. The land needs reform, not rewilding, says Gibson, for the common good and public interest. "Mr Lister," he says, "doesn't meet either of these criteria."

Your pictures

We asked readers to send us their pictures of wolves, you can see a selection here.

Yet Lister believes his wolves would stimulate the local economy and bring in 20,000 visitors a year. A study on the Isle of Mull supports this, where the reintroduction of the sea eagle has brought £5m a year to the island, and supports 110 jobs, Monbiot noted in his book Feral.

The arguments go back and forth, and those that I meet as I walk through the Highlands are equally divided. One night I stop in the bothy at Ruigh Aiteachain, and it isn't long after I have explained my journey to those sitting around the fire that the debate is getting heated.

"It would make me more scared to walk," says one man. "I grew up in the country and I still wouldn't like them. I think it would backfire. Especially with kids and old folk around."

"A few might be okay," says his son. "But if there were thousands of them, getting into packs. You'd have urban wolves. I wouldn't want that."

"I'm from Poland," says a woman. "We're used to them. Animals don't scare me. I think people are the most dangerous species on earth."

"I'm all for it," says another. "To be lying in your tent in the middle of nowhere and to hear a wolf cry. Now that must be quite something."

A map showing the distribution of wolf populations throughout Europe

I stop at the Inverness Museum to meet Cait McCullagh, archaeologist and curator. I had crawled from my tent on the north side of the Beauly Firth two hours earlier and rushed across Kessock Bridge with the morning commute to make the meeting.

I have come to see the Ardross Wolf Stone, a Pictish carving from the 6th or 7th Century. It is a beautiful piece: head down, mid lope, the curves of its line speak of movement and of muscle. "It's clear from the art that they are people who are hunting these animals," says McCullagh. "There's an observational quality that I think comes from spending a lot of time with the animal out in the field."

It is the most tangible sense I have yet had that once there were wolves that walked here. I could touch this carving before me, this carving done by someone who had seen a wolf, many wolves, 1,300 years and 30 miles away.

The wolf was once the most widely distributed land mammal on the planet, except for us. They were more or less eradicated in Wales by the 10th Century, and in England by the 13th. They were destroyed in part to protect livestock, and in part because of what they had come to represent.

Since Jesus has been associated with the lamb, the wolf has been associated with the Devil. For Doug Richardson, head of living collections at the Highland Wildlife Park, this is the biggest impediment to a reintroduction. "It's all doable, and I personally think it's worth doing," he says.

"The problem is dealing with the mythology. The Little Red Riding complex. The lying cow killed her grandmother, blamed the wolf, became a fairytale." He shrugs. "The rest is a nightmare."

Doug Richardson at the Highland Wildlife Park: Re-introducing wolves "is doable and... worth doing"

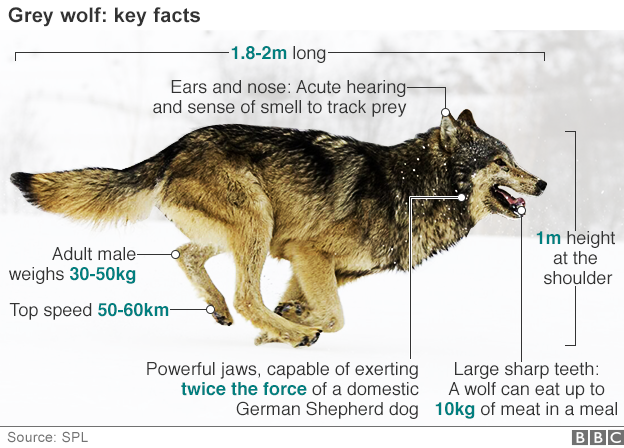

I have come to the Wildlife Park to see the wolves. After two weeks of walking and talking about them, the prospect of seeing them in the flesh is tantalising. There are four of them, all females, stretched out on the roof of their shelter, the muzzle of one upon the flank of another.

And unlike the Bactrian camels grazing nearby, they look entirely at home on this wet and chill spring day. It is the bars which seem to have imposed. Their pelage is the colours of the forest - the browns of the earth and the greys of the pines and the faint blue of the lichen. Chaffinches and pied wagtails flit above them.

One stands, stretches with her forelegs out, her back a low curve. She jumps from the roof and paces, sniffing, moving through the enclosure in a fluid, loping trot. There is something so close to familiar - I know these movements from every dog I have ever seen.

Before the horse, before the sheep, before any other animal, it was the wolf that we domesticated. She returns with a bone and bounds to the roof, pins it with a paw and begins to crack it with her molars.

-

Beaver

×Beaver: Hunted to extinction for fur, meat and medicine, they were officially reintroduced to Knapdale Forest in Argyll, south-western Scotland, between 2009-10. The trial is the first formal reintroduction of a mammal to take place in the UK. Colonies that have recently appeared on the River Tay in eastern Scotland, and the River Otter in Devon, are of more mysterious provenance. In June 2015 it was reported that one of the females living on the River Otter had given birth.

-

Goshawk

×Goshawk: Wiped out in the 19th Century, partly due to deforestation and relentless persecution by gamekeepers. Unofficially re-introduced from the 1960s onwards by falconers and hawk-keepers, some were deliberately released and others escaped into the wild. There are thought to be about 500 pairs in Britain - 150 of them in Scotland, mainly in the borders, the north-east and Dumfries and Galloway.

-

White-tailed sea eagle

×White-tailed sea eagle: Became extinct in the early 20th Century, reintroduced to the Isle of Rum, one of the islands of the Inner Hebrides, in 1975. The white-tailed eagle is the largest UK bird of prey, with a wingspan of about 2.45m (eight feet). Numbers are still very low as work to reintroduce the species has been hampered by the theft of eggs.

-

Osprey

×Osprey: Having disappeared from the British Isles by the start of the 20th Century, they began breeding again at Loch Garten in Strathspey in 1954. Since then conservationists have worked hard to encourage the population to increase by protecting nests and introducing the bird to other sites in Britain. There are now estimated to be between 200 and 250 breeding pairs.

-

Reindeer

×Reindeer: The most recent fossil evidence is 8,300 years old. Reintroduced into the Cairngorms in 1952, there is a single herd of about 150 animals. They range freely in the highlands, but are tame and popular with tourists.

-

Great bustard

×Great bustard: Hunted to extinction in 1832, they were reintroduced to Salisbury plain in 2004, with the first chick fledging in 2009. The great bustard is one of the heaviest flying birds alive today - the male bird can reach up to one metre tall (3ft3in) and weigh 16kg (35lb).

-

Red kite

×Red kite: Reduced to a handful of birds in Wales, the red kites were released in north Scotland and the Chiltern Hills in Buckinghamshire in SE England during the late 80s and early 90s. Successful breeding populations have become established in both locations and since then more birds have been released in other locations. There are now thought to be more than 1,000 breeding pairs in the Chilterns alone.

-

Large blue butterfly

×Large blue butterfly: First recorded in 1795, the large blue was extinct by 1979 due to loss of suitable habitat. Following a reintroduction with Swedish stock, there are now estimated to be more than 10,000, spread over 11 sites, mainly in south-west England, including the Polden Hills in Somerset, Dartmoor and Gloucestershire.

-

Pool frog

×Pool frog: Became extinct in England in the 1990s. About 70 from Sweden were reintroduced in Norfolk in 2005. The pool frog has since beeen reintroduced at a number of other sites, including Hampshire, Surrey and Essex. Latest evidence suggests they are now well-established and breeding.

-

Lynx

×Lynx: Applications have been submitted for a five-year trial to release around 18 lynx at sites in Norfolk, Cumbria, Northumberland and Aberdeenshire. Reintroductions into other European countries have been remarkably successful. The lynx hunts deer and smaller prey such as rabbits and hare, and is not regarded as a danger to humans.

- ×

A BBC Countryfile poll, external found the wolf to be the most popular animal for a UK reintroduction. Yet Richardson suggests that a referendum would be unjust, and says that nothing should go ahead without the farmers and the gamekeepers on board, for the good of both the people and the wolves.

"Those two groups, they're the lock," he says. "Everybody else doesn't have many cards in the game. When you've got six, seven, eight generations doing that job, you've got to have a degree of compassion about their livelihood."

The final definitive record of a wolf in Scotland is for 1621, but myth places the date much later, to 1743, and a man named MacQueen. The story sounds improbable: the wolf was huge and evil, MacQueen was huge and handsome, the wolf had just eaten a child.

But a day's walk south of Inverness, a few miles from where the killing took place, I come across David MacQueen, his descendant. Like his ancestor he is a hill farmer, with 600 head of sheep.

Farmers such as David MacQueen are sceptical about re-introducing wolves

The National Farmers' Union of Scotland is strongly opposed to the wolf's return. In Europe shepherds are learning to live alongside them, with a mix of old techniques and modern technologies - keeping large dogs to protect their flocks, or using collars that monitor the sheep's heart rate and text the farmer if they are showing fear.

But MacQueen points out that it is hard enough to scrape a living as it is. "You're wanting people to be farming efficiently," he says, "keeping up with the times as it were, and then some joker that you see once in a blue moon is saying we're going to put all these beasts of prey and raptors back and they can all just help themselves. That maybe grates a wee bit."

In Europe compensation is paid to farmers who lose stock, an average of two million euros annually across France, Greece, Italy, Austria, Spain and Portugal, according to Monbiot. Yet many feel their livelihood is under threat, and are shooting livestock illegally.

In Italy corpses are being left in town squares, with calling cards signed by Little Red Riding Hood. MacQueen believes no amount of money would make up for losing one of his best ewes, and is sceptical about the amount of red tape that would be involved to claim any money back.

A short walk up the road from MacQueen's farm is the village of Tomatin. Outside the shop I meet Allan, a gamekeeper on one of the local estates. We get into his Land Rover and he drives me up to the land where he works.

Allan the gamekeeper: "The wolves were killed out for a reason"

Allan's face is both sun- and wind-burnt. He has a sandy moustache and is dressed in army fatigues. "I'm getting paid to do my hobby," he says. "I'm supposed to go on holiday. I'd never leave the place if the wife didn't make me go." We stop on a rise among the heather and he shuts off the engine.

We sit there, the windows down, listening to the crackle of birdsong, looking out across forest toward mountains dim and blueish in the distance.

"People think this is a wilderness and there's tons of room up here," he says, turning to me. "Look at it. All these trees are planted by man. We can't quite see the Cairngorms, but that's about the only bit of wilderness in Scotland and there's people all over it.

"Wilderness doesn't exist. Man manages this now. Scotland's changed forever. Unless they're going to get rid of the population and have a few hunter-gatherers. The wolves were killed out for a reason. They were a problem, to agriculture and people living in the countryside. That's why they were done in."

'Last wolf' mystery

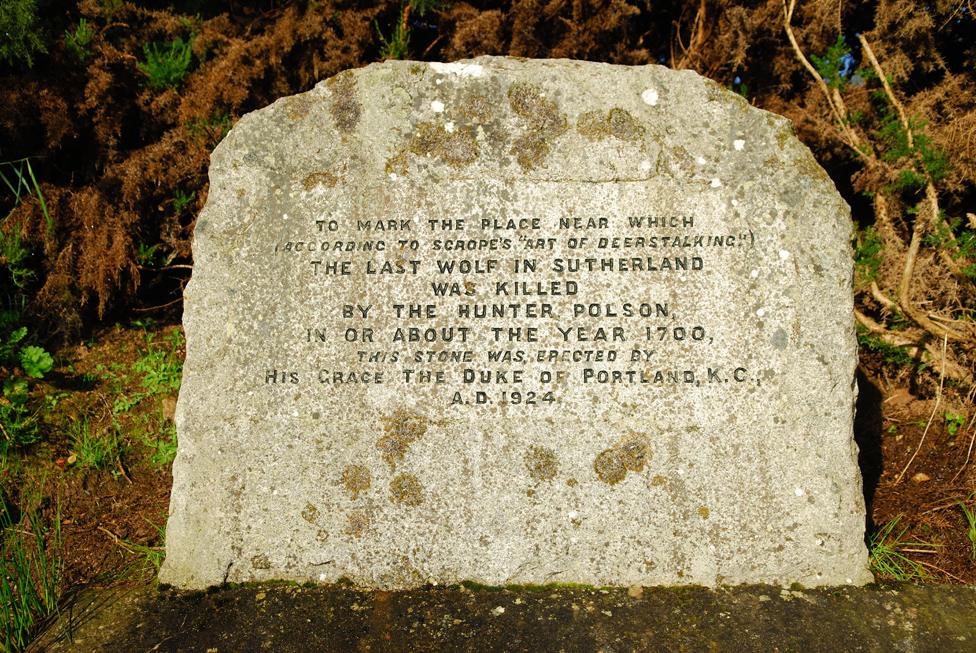

MacQueen killing a wolf in 1743 is but one of many "last wolf" stories in Scotland.

On the A9, a few miles south of Helmsdale, is a memorial stone to mark the place where "The last wolf in Sutherland was killed by the hunter Polson in or about the year 1700".

Yet this is 20 years later than the date given for the demise of another last wolf, at the hands of Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel in Killiecrankie Gorge. This wolf was stuffed and turned up more than a century later when the London Museum's collection was auctioned off. "Lot 832 WOLF, a noble animal, in a large glazed case."

Yet another is set in Strath Glass, at a date unspecified. An old woman had gone to the north side of the strath to borrow a skillet, and sat down to rest on some stones on her way home. As she was resting, a wolf crept up on her. Yet instead of fleeing, "she dealt him such a blow on the skull with the full swing of her iron discus, that it brained him."

Source: James Edmund Harting's British Animals Extinct Within Historic Times (1880)

Scotland may not be wild, but I have walked for days without seeing anyone - the population density in the Highlands is comparable to Chad. Besides, wolves do not depend on wilderness. They have been recently seen in countries as populated as Belgium and the Netherlands.

The question is not whether there is enough space, but whether wolf and man can cohabit in what space there is.

"They've all got their woolly hat and their beard," says Allan, "and they've all been to college, and they're all taught the same thing. That it'd be better if man didn't exist on this planet. That we've got an adverse effect, we're not part of the ecosystem, that we shouldn't interfere with anything.

"We've as much right in this place as anybody else. It's going to cost some people millions. And it's not going to cost the people who think it's a good idea a penny." For Allan, and others like him, rewilding is finishing the work of the Clearances, shifting those who belong off the land for commercial gain and the benefit of outsiders.

Yet perhaps a balance can be struck. On the last day of my walk I go to watch the beavers that have re-colonised the Tay, external. I had expected a mammal that can grow as big as an Alsatian to stand out in a landscape where they have not been known for centuries, but they merge into the riverbanks as though they had never left, more a hiatus than an extinction.

This is not a wilderness by anyone's definition of the word - it is a few metres of riverbank at the end of some fields, a 10-minute walk from a 24-hour Tesco.

Richardson thinks that it is our definition of wilderness that needs reconsidering. "People have this idea that if you put a fence up that it'll be artificial," he says. "This outdated idea we have of 'the wild', it pretty much doesn't exist. People say you'd need to constantly manage the wolves because it's a finite area. Well, the vast majority of the planet is managed in one way shape or form. That's just the way it is."

Or as Allan, the gamekeeper, puts it: "In a country where you haven't got a wilderness, you have to play God."

Adam Weymouth is a writer and a walker, on Twitter @adamweymouth, external.

Additional research by James Morgan and Dhruti Shah

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.