The man who keeps finding new species of shark

- Published

Most people have heard of great white, hammerhead and tiger sharks but there are many other species - and every year a number of new ones are discovered. One enthusiast has, so far, identified 24 types of shark and related fish that were previously unknown.

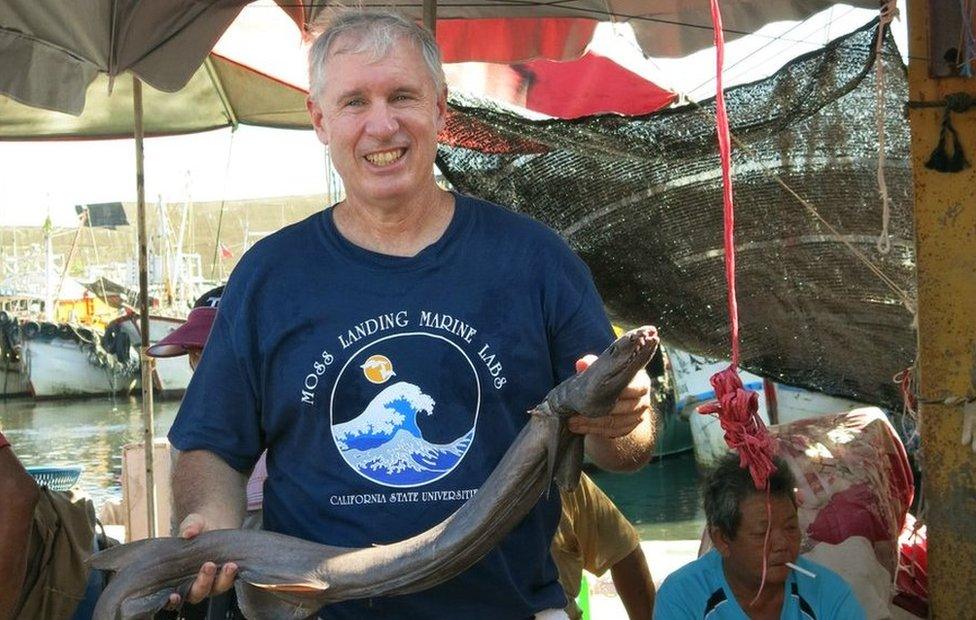

Dave Ebert has a favourite market in Taiwan. He's been going there since he was a student 30 years ago.

It's hot, humid and noisy - baskets are filled to the brim with a staggering variety of fish. Beach umbrellas provide some relief from the sun as puddles of water collect on the concrete floor.

"I started seeing a lot of species and I was going, 'What the heck is this?' And in many cases it was a known species but we didn't know it occurred here. Then I realised there were some species we didn't even have names for, they weren't even known about, and here people were catching them and selling them," he says, remembering his first visit.

"I collected so many specimens I filled up my suitcases. I rinsed them in water and preserved them in ethanol and basically just wrapped them up in my clothes to keep them moist and put them in plastic bags so they wouldn't leak."

The fishermen, wary at first, soon warmed to him. "Now when I go back, they know me and if they've brought in something unusual they'll come and find me. That's how I've found some really cool stuff.

Ebert with a frilled shark caught by Taiwanese fishermen © Dave Ebert / PSRC

Bull sharks at the market © Dave Ebert / PSRC

"It is organised chaos… you have maybe 50 to 70 boats and I'll just sit there and watch them come in. I basically have this whole village out fishing for me," he says.

He has found 10 new species in this market alone. In all, over the past three decades, Ebert has named 24 new species, including sharks, rays, sawfish and ghost sharks - these cartilaginous fish are all related.

He discovered his first while he was on a research ship off the Namibian coast in the late 1980s.

Ebert in the Namibian desert, 1987 © Dave Ebert / PSRC

"I did a lot of work along the skeleton coast. We would just head off and tell someone we'd be back in a couple of months and if you don't hear from us for 10 weeks come look for us.

"We'd go up to some of the towns to get supplies and then just go fishing along the coast to see what you could catch, no-one had really surveyed along there."

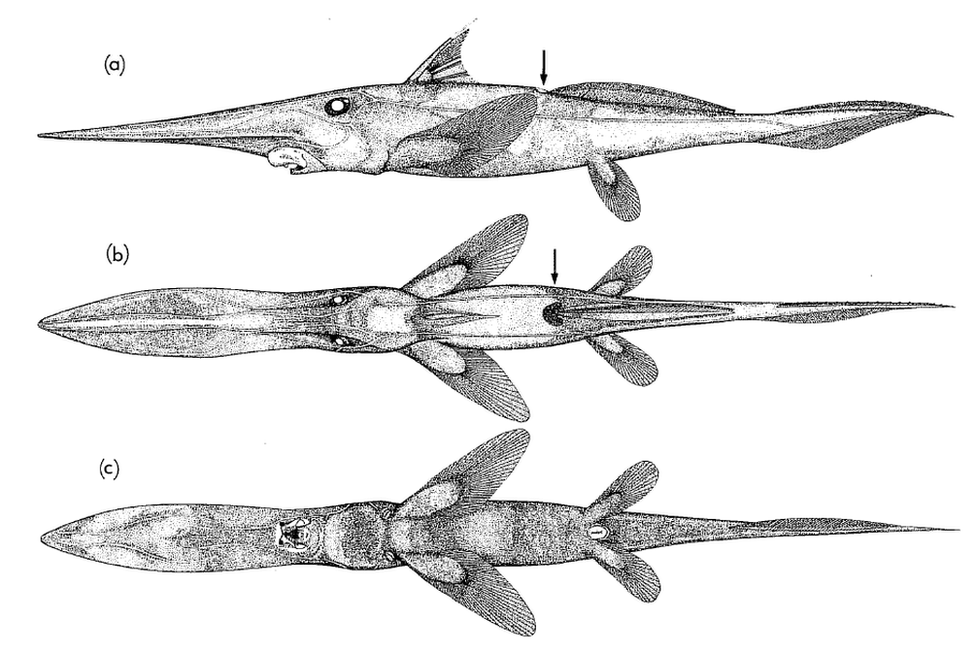

It was one of these trips that he found a paddlenose ghost shark, which he affectionately refers to as Paddlenose Pete.

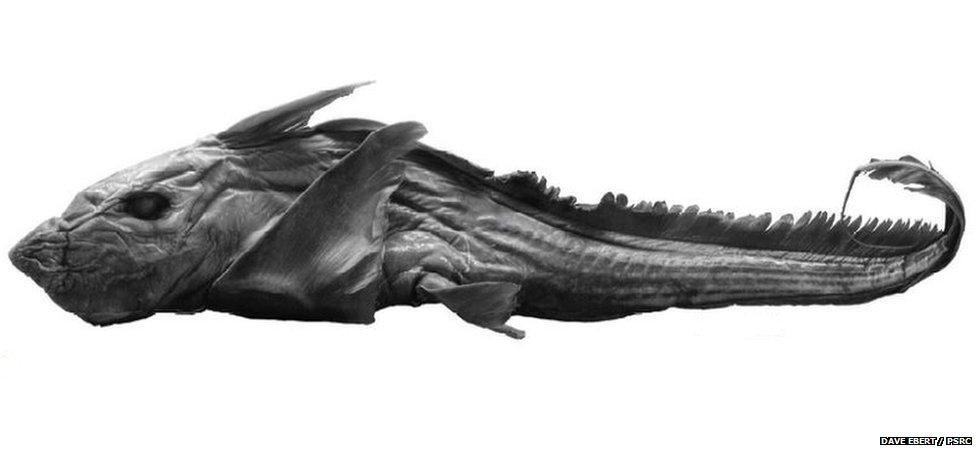

Paddlenose Pete © Dave Ebert / PSRC

The southern African frilled shark © Dave Ebert / PSRC

On the same coast, before long, he came across another new species - the southern African frilled shark.

"I was at sea and I was just thinking, 'This sure looks different,' but at that point you think you're either losing your mind or you're really on to something. It took me about 20 years but I finally got it named in 2009," he says.

He named another after his shark-loving niece as a graduation gift - Pristiophorus lanae or Lana's sawshark.

Lana's sawshark © Dave Ebert / PSRC

And he's made other discoveries much closer to home. Once, he and a student were classifying a new species of ghost shark that he had found in Africa.

They asked a museum to send a specimen of a similar species from its collection to help with identification - but what arrived in the post wasn't what they expected.

"My student opened up the package and looked at it and she says, 'I don't think this is what it's supposed to be Dave,' and I looked at it and I had no idea what it was.

"In fact, it had been labelled incorrectly and was actually a completely new species, so we ended up naming that one too. It was a new ghost shark from the Bahamas… it was nice for it to just show up on our door!" (The Chimaera bahamaensis, or Bahamas ghost shark, is pictured at the top of the page.)

Ebert estimates that he has another 30 or so new species of sharks, rays, and ghost sharks in his collection in California waiting for formal identification.

He keeps them in glass jars of preserving fluid that line row after row of shelves at the Pacific Shark Research Center at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, where he is research director.

"Sometimes you have that eureka moment where you just know that's a newbie. More often than not though you look at it and think this one needs looking at more closely. I'm usually a little reluctant to jump up and down immediately," he says.

Formally identifying a new species can take months or years. Comparisons with other similar species have to be made, measurements must be noted and a detailed description of its appearance recorded.

Diagram of the paddlenose ghost shark © Elaine Grant and Leonard Compagno / South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity

Technology can't replace traditional methods, says Ebert. "Today there are a lot of molecular tools available but you have to be careful as you can literally get an ant and an aardvark to come out genetically the same if you want."

Once the physical and genetic characteristics have been identified, the species needs a name. This needs to be registered and approved by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.

As well as looking for previously unclassified sharks, Ebert also documents what fishermen catch. "There are species that 27 years ago were really common and now you don't really see. Then other species I never used to see are now caught all the time.

"Twenty-five years ago these fishermen would be catching fish [at depths of] 100m and 200m. Now they say they have to fish down to 900m." Scientists believe that many new sharks could be discovered at these depths.

A new species of rough shark © Dave Ebert / PSRC

Finding new species is not as unusual as it might sound. Last year 18,000 new species of animals and plants were identified.

"There are few places on Earth where you can go and not be in the proximity of undescribed species," says Quentin Wheeler from the International Institute for Species Exploration. "But until scientists can determine where they fit into the evolutionary relationship, and give them formal names, we don't consider them officially known."

At the moment, scientists know of more than 500 species of shark - a fifth of which have been found in the past decade.

"You really are being an explorer," says Ebert. "Whether you're going to a market or going out to sea. Little kids tend to go through that dinosaur and shark phase in life and I never grew out of it. My parents gave me a little shark book when I was about five - I still have it - and I was just fascinated.

"When I was 10 years old I told my folks, 'I'm going to travel the world and study sharks,' and they told me to 'follow your dream'. I love it. I get to experience things that most people never will."

© Dave Ebert / PSRC

Quentin Wheeler spoke to Newsday on the BBC World Service.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.