The dentures made from the teeth of dead soldiers at Waterloo

- Published

In 1815, dentistry as we know it today was in its infancy - and the mouths of the rich were rotten. So they took teeth for their dentures from the bodies of tens of thousands of dead soldiers on the battlefield at Waterloo.

In the late 18th and early 19th Centuries "everyone was dabbling in dentistry", says Rachel Bairsto, curator of British Dental Association's museum in central London, external. From ivory turners to jewellers, chemists, wigmakers and even blacksmiths.

Among the wealthy, sugar consumption was on the rise and early attempts at teeth-whitening - with acidic solutions - wore away enamel.

Teeth were being pulled. The demand for false teeth was growing. Business was booming.

There is evidence from the years before the Battle of Waterloo, says Bairsto, that early dentists did place human teeth in dentures.

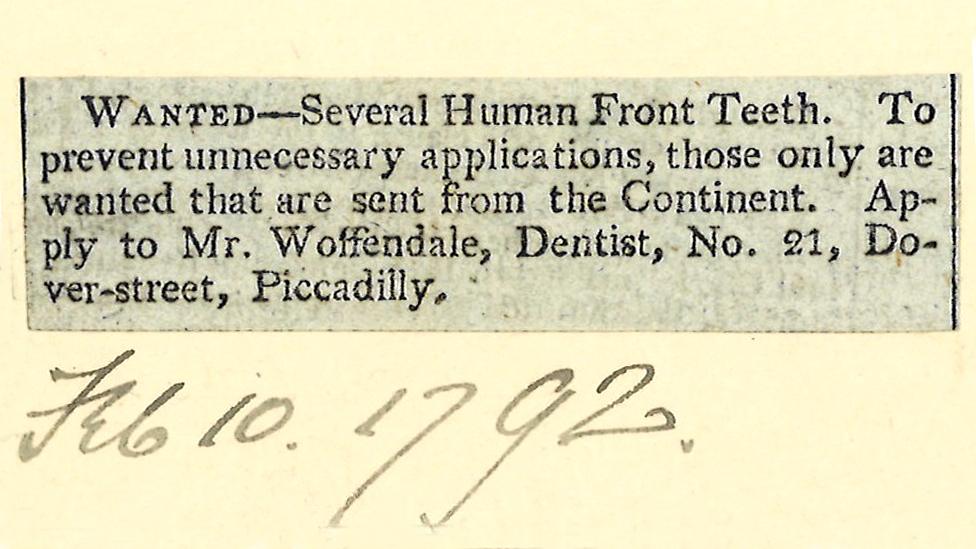

This advertisement above, from 1792, calls for foreign teeth - which would have been riveted into ivory dentures and placed into unhealthy British mouths.

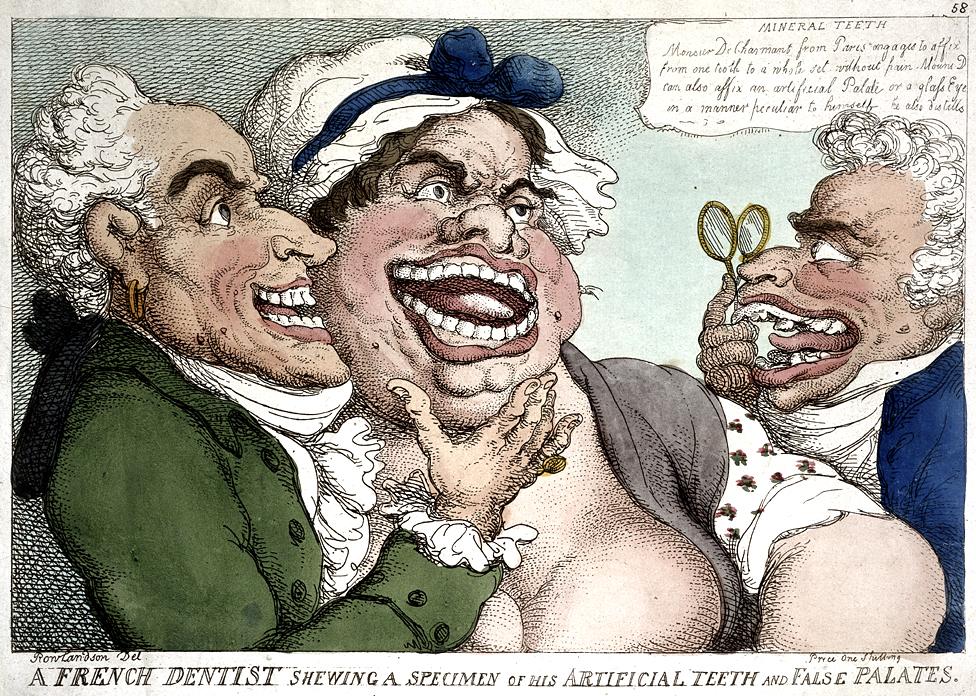

And cartoons from the period - like the one below from Thomas Rowlandson in 1787 - show teeth of the poorest in society being yanked out. They were live donors for the benefit of more wealthy dental patients.

At this stage, the dentures' base plate was ivory, with human teeth attached. Another option was to have ivory "teeth" as well.

In the 1780s, says Bairsto, an ivory denture with human teeth could cost over £100. Without human teeth it was cheaper, but still financially out of reach for most people.

Despite the huge cost - because the dentures were likely to have been put into unhealthy mouths - they probably would not have lasted very long.

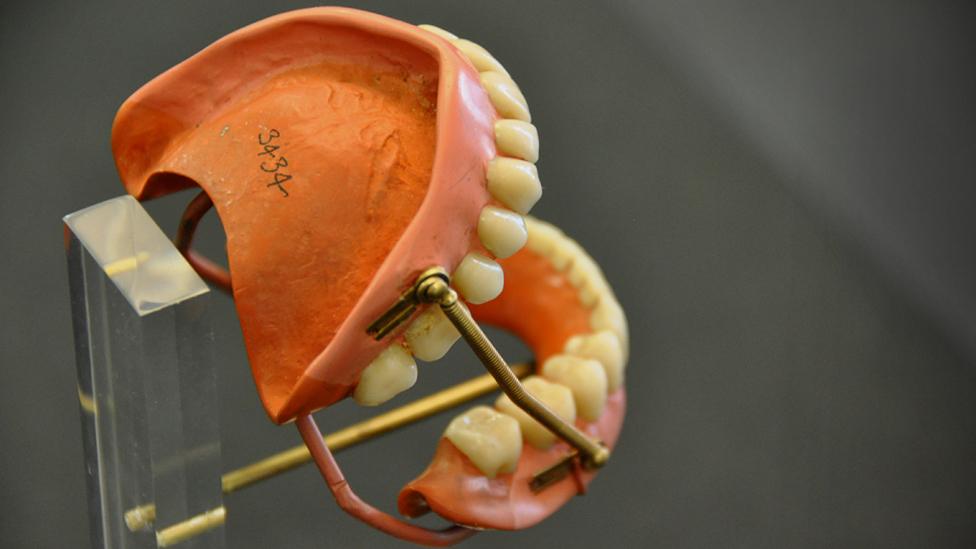

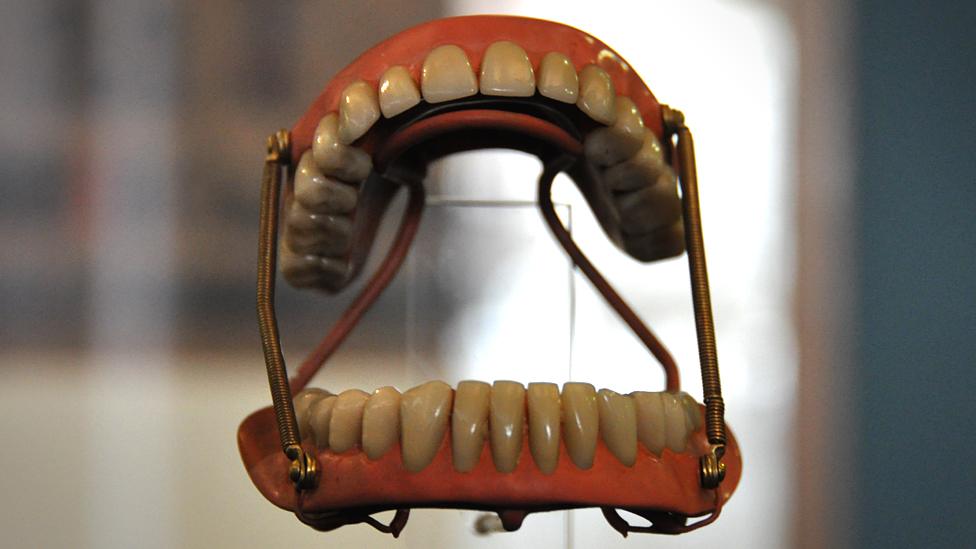

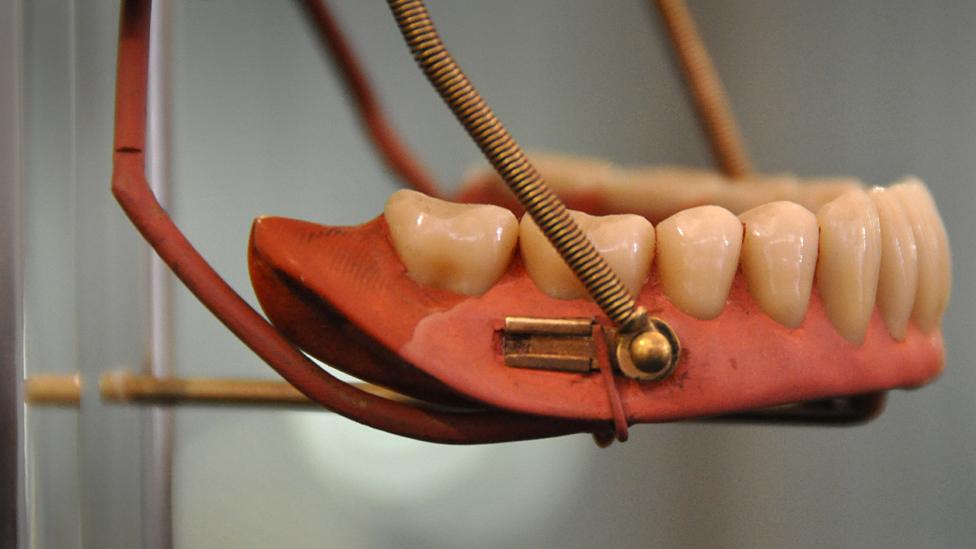

These next pictures show full upper and lower ivory dentures, held together by piano wire springs.

Ingenious for the time, but likely to be very uncomfortable to wear, awkward to eat with, and prone to falling out easily.

And so human teeth, set in a denture, were more desirable. But the number of live donors was finite, and grave robbers could offer only limited supplies.

The prospect of thousands of British, French and Prussian teeth - sitting in the mouths of recently-killed soldiers on the battlefield at Waterloo - was an attractive one for looters.

There were lots of bodies in one place and above ground - says Rachel Bairsto. The teeth would have been pulled out with pliers by surviving troops and locals - but also by scavengers who had travelled from Britain.

This next picture shows teeth taken from Waterloo strung up for sale.

They would have been shaped and sorted - says Bairsto - to make it look like each set of upper and lower front teeth had come from a single body.

The sets would have been sold to early dental technicians who would boil them, chop off the ends, and then shape them on to ivory dentures.

Rachel Bairsto says fewer molars would have been taken from the battlefield - because they would have been trickier to pull out and would require a lot more shaping.

The term "Waterloo teeth" is known now, but Bairsto says she has struggled to find proof that they were known as such at the time. Perhaps people had no idea that their fresh set of dentures contained the teeth of fallen soldiers, she adds.

In the middle years of the 19th Century, the use of human teeth in dentures declined.

Partly because of the 1832 Anatomy Act which licensed movements of human corpses - and partly because new products were emerging which could take the place of real teeth.

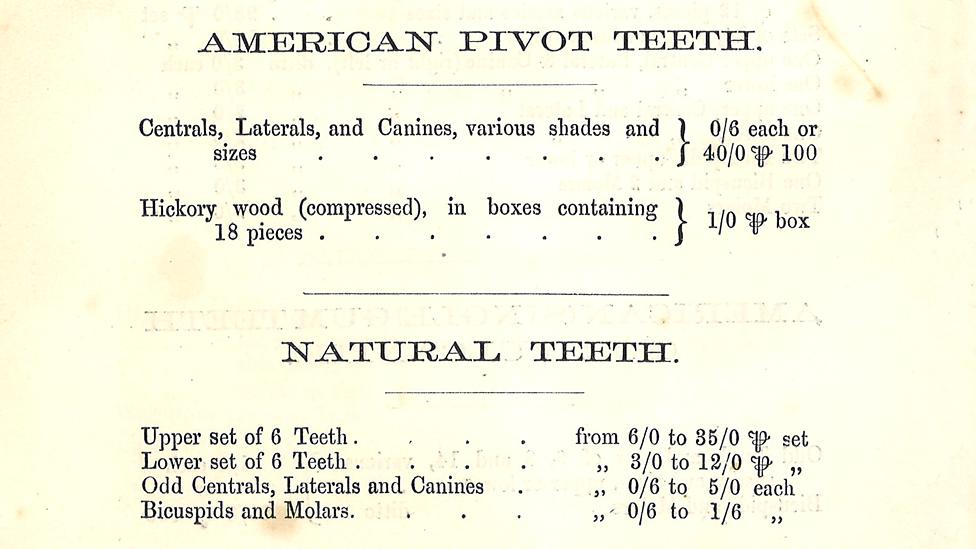

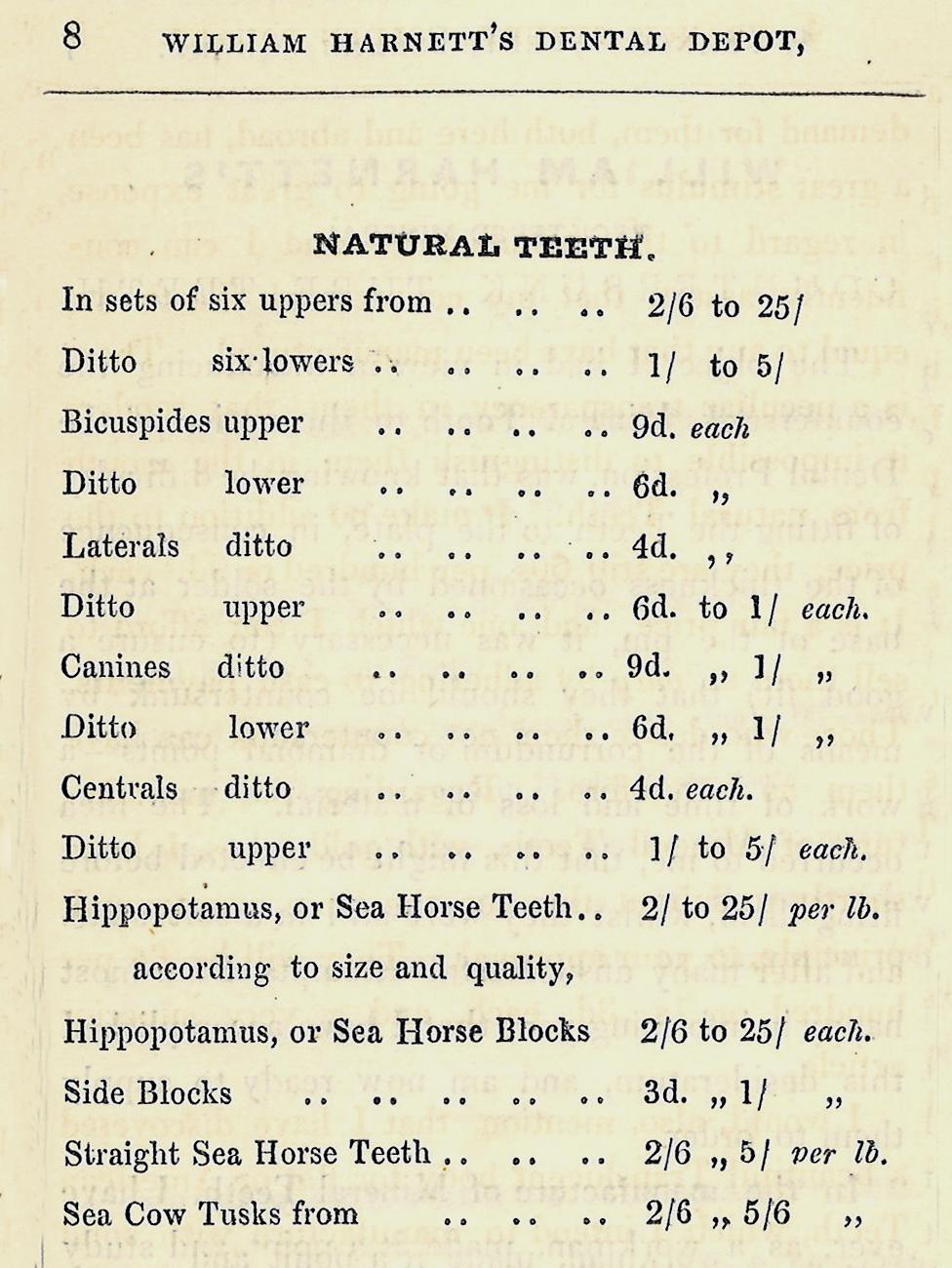

But as this price list from 1851 shows, dentists were still able to make purchases - of both human teeth and ivory.

Technicians were experimenting with different ways of attaching teeth to dentures - such as metal pins.

The first half of the 19th Century also saw the introduction of porcelain teeth - with jeweller Claudius Ash credited with making significant advances in this area in the 1830s - when he developed his "tube teeth".

The next big breakthrough was the use of vulcanite as a base for dentures - replacing ivory. Developed in the 1840s by American brothers Charles and Nelson Goodyear, it's a compound made from India rubber. It was relatively cheap - but also pink, very nearly gum-coloured.

At the time of the Battle of Waterloo, says the BDA Museum's Rachel Bairsto, anyone could call themselves a dentist and give you advice about your teeth. You might even go to a jeweller to get your dentures adjusted.

It took another 45 years before the UK introduced the first qualification for dentistry. And nearly another 20 years, before the first dental legislation was passed (1878) and a register of dentists created (1879).

From pulling incisors from bodies on the Belgian battlefield, to porcelain teeth set in vulcanite dentures - there were significant advances in dental care in the 19th Century. But it would be well into the 20th Century - with acrylic replacing vulcanite, and fluoride put into toothpaste - before the next big improvements would arrive.

All images subject to copyright. Images courtesy British Dental Association Museum, external.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.