How two men survived a prison where 12,000 were killed

- Published

Tuol Sleng is Cambodia's most notorious prison - in the 1970s, at least 12,000 people were tortured there and murdered. Only a handful of prisoners survived but now, 40 years after Pol Pot took control of the country, two of them return to the cells every day to remind people what happened.

Chum Mey had never heard of the CIA before, but after 10 days of torture he was ready to confess to being a secret agent for the US.

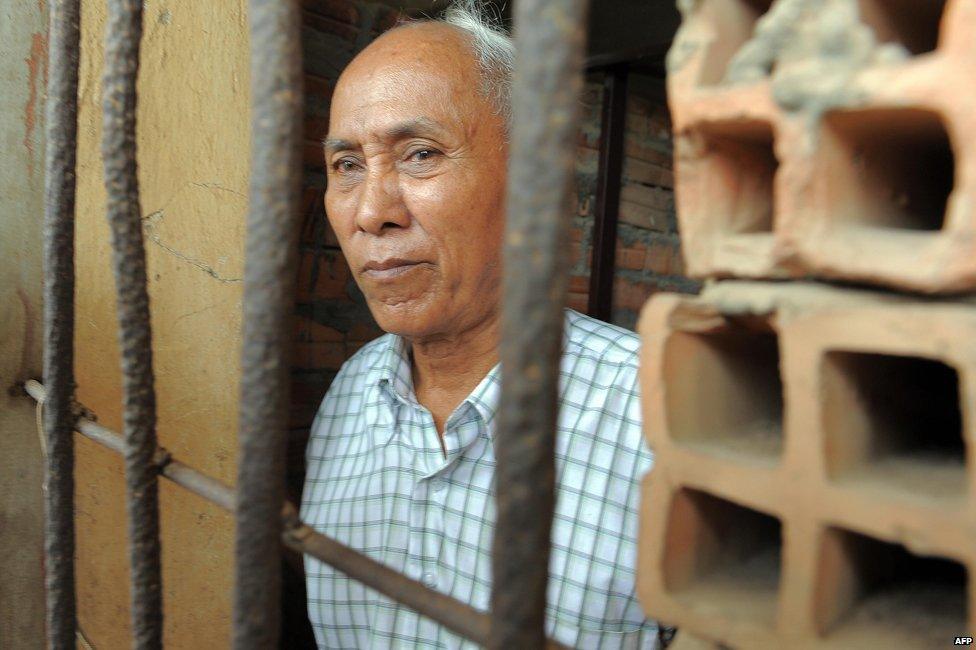

We are in Tuol Sleng prison, Phnom Penh, in the very cell where he was held. Almost four decades on, Chum Mey still has nightmares and yet he returns to this place every day.

"If those guards hadn't tortured a false confession out of me, they would have been executed - I can't say I would have behaved any differently [in their position]," he says.

Tuol Sleng, codenamed S-21, was converted from a school to an interrogation centre on the orders of Pol Pot when his Khmer Rouge movement took control of Cambodia in April 1975.

Pol Pot, who was born Saloth Sar

At least 12,000 people who were held here were killed. Just 15 prisoners survived.

Eighty-three-year-old Chum Mey is one of the few still alive today. Bou Meng, 74, is another. One a mechanic, the other an artist, their practical skills were useful to the Khmer Rouge and their impending death sentences were put on hold.

For the past three years, the pair has taken up a sort of day-residence at S-21, which is now preserved as a genocide museum - this is how they have chosen to spend their retirement.

They are also allowed to sell their memoirs - at $10 a copy, they make a modest living this way.

There is something ambassadorial about their presence. They are celebrity survivors, modern-day reminders of Cambodia's dark past.

"The important thing is to document what happened here," says Bou Meng. He sits at a stall in the prison courtyard, decorated with a large banner that reads: SURVIVOR. "I want people around the world to go home and tell their friends and family about the genocide of the Khmer people."

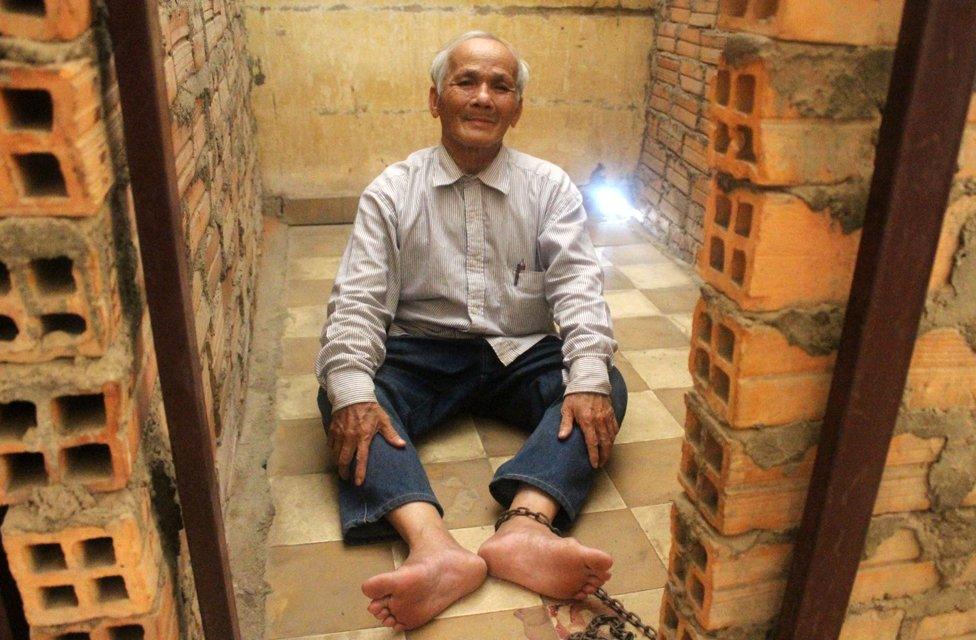

Bou Meng shows how he was restrained © Kirstie Brewer

© Kirstie Brewer

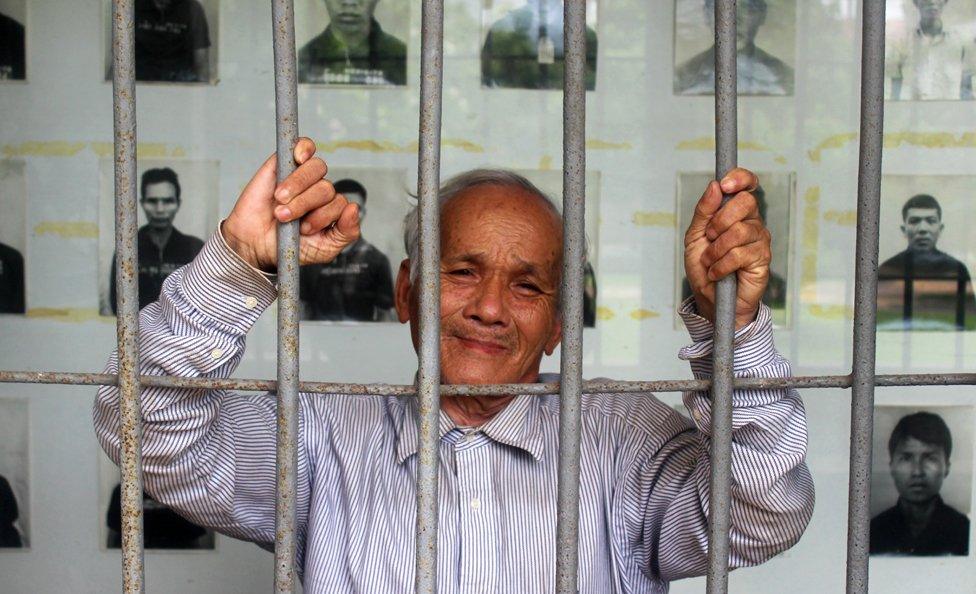

Buy their books and you'll be presented with a business card and encouraged to sit down with them for a photograph. They recognise the potency of photographs. The museum houses row upon row of headshots taken of prisoners when they first arrived.

I accompany them both separately on a walk around the museum. Like living artefacts, they shuffle in and out of the cells, nodding their thanks to visitors and studying the photographs on the walls.

"So young," says Chum Mey, gently tracing his finger along a row of teenage boys and girls.

They say they are haunted by the faces that look back at them and that these faces compel them to return every day and tell their stories.

Chum Mey had been working as a mechanic for the Khmer Rouge, when suddenly he was arrested on 28 October 1978 and taken straight to S-21. He still doesn't know why.

"I was blindfolded and my hands were tied behind my back - I pleaded with my captors to let my family know where I was," he recalls.

"Angkar [the ruling body of the Khmer Rouge] will smash you all," a voice hissed in his ear.

Upon arrival, after being measured and photographed, prisoners were stripped and shackled to the floor of a cell barely big enough to sit down in.

"After that I cried because I felt so hopeless and confused," says Chum Mey. In the 12 days that followed, he was taken from his cell three times a day and tortured in one of the prison's interrogation rooms.

One of the rooms where prisoners were tortured

Two guards took turns beating him with a stick covered in twisted wire. Eventually they decided to pull out his big toenail. He looks down at his feet and explains in unflinching detail how the guard tugged and twisted the nail until it came out.

"I could tolerate the pain of being beaten and even having my toenail pulled out, but it was the electric shocks I was terrified of," he says, tapping the side of his head.

These were administered by electrodes placed inside the ears. Chum Mey is deaf in one ear as a result and says he hears the sound of rushing water when he moves his head.

"It felt like my eyes were on fire and my head was a machine - after that I started telling them whatever they wanted to hear. I didn't know what was right or wrong any more."

A painting by Bou Meng © Kirstie Brewer

He sits down at the desk where his confession was typed up by his two interrogators. In front of the desk is a bed frame and heavy iron shackles. There is dried blood on the ceiling. A photograph on the wall shows an emaciated man lying on the bed with his throat cut.

Most of the people who ended up in these cells were Khmer Rouge cadres and their families, accused of collaborating with foreign governments or spying for the CIA or KGB.

"The regime was a breeding ground of paranoia," explains a museum guide. "Soldiers would grow to know too much and then they themselves could be subject to torture and death."

Chum Mey's fellow survivor, Bou Meng, was originally a Khmer Rouge supporter - an artist by trade, he had painted some early propaganda posters.

He and his wife were arrested on 16 August 1977. "They screamed in my wife's face that Angkar had never arrested the wrong person," he recalls.

The first thing Bou Meng does when we sit down in the prison courtyard is show me an illustration he has drawn of his wife.

"Ma Yoeun," he says with tears in his eyes, gesturing for me to repeat his late wife's name. In the picture she is screaming, stooped over a mass grave, and her throat has been cut.

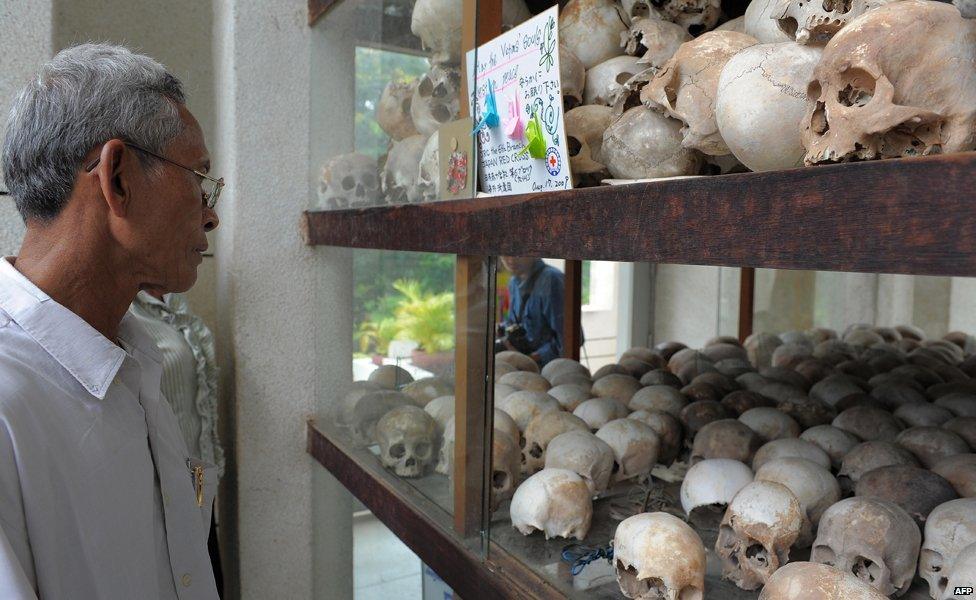

Most S-21 inmates were eventually trucked by night to Choeung Ek - one of the sites that became known as the Killing Fields. A team of teenage executioners would be waiting - they were told ahead of time how big a grave to dig.

Visitors can see the skulls of some of the victims at the museum

Ma Yoeun was a midwife but only Bou Meng was deemed worth saving. "Why couldn't they keep her alive too?" he asks. "She only ever looked after people."

The couple had been separated on arrival at S-21. Bou Meng was photographed and taken to a large holding cell filled with emaciated prisoners.

Like Chum Mey, he was relentlessly questioned and beaten - he shows me the scars on his back. He too is deaf in one ear as a result of regular torture.

Prisoners were given two ladles of watery porridge a day. Chum Mey was so hungry he would eat the rats that scurried into his cell.

A small ammunition box served as a toilet. "If any waste spilled out we had to lick it from the floor," he says.

Bou Meng still remembers the oppressive stench in the air. "At first I thought it was something like dead fish or mice because I had never smelt rotting human flesh before."

After several months of interrogation, Bou Meng also relented and gave a false confession, admitting to being part of a CIA network, and naming other "collaborators".

Painting portraits "saved my life," he says. When the prison chief, known as Duch, found out that he was an artist, he told him to reproduce a black and white photograph of Pol Pot. Duch warned him that if it wasn't lifelike he'd be killed.

Comrade Duch during his trial at the UN-backed war crimes tribunal

Bou Meng took three months to finish the painting - it was 1.5m wide and 1.8m high.

Pleased with his work, Duch later requested large portraits of Karl Marx, Lenin and Mao Zedong, as well as several more of Pol Pot. Bou Meng was also told to draw the Vietnamese communist leader, Ho Chi Minh, stranded on a rooftop in the middle of a big storm.

"I don't know why Duch needed these paintings, and I didn't dare to ask," he says.

Duch kept Chum Mey alive because he could fix typewriters - crucial for taking down confessions. He also fixed sewing machines, used to make thousands of black Khmer Rouge uniforms.

In 2009, both men testified at a UN-backed war crimes tribunal against Duch - a former Maths teacher who became the architect of the torture and execution methods at S-21. Like their return to S-21, it has helped bring them some solace.

S-21 was a microcosm of what took place across Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. An estimated 90% of artists, intellectuals and teachers were killed in an effort to return the country to "Year Zero" - Pol Pot's vision of a classless, agrarian society.

By the time Pol Pot fell from power, about two million people - a quarter of the population - had been murdered, starved or struck down by disease.

Bou Meng's two young children were among those who died from disease during the Pol Pot years and it was only during the 2009 war crimes tribunal that he learned his wife had probably ended up in a mass grave.

He returned to the prison in the 1980s to look for Ma Yoeun's photo as well as his own.

Bou Meng with the photo of his wife, taken at S-21 © Kirstie Brewer

He shows me a copy of the photo taken of his wife when she first arrived here - he never found his own. "I see her here, in front of us right now," he says, staring into the middle distance. He would like to be able to visit her grave and say prayers over her bones.

Testifying at Duch's trial, he was given a chance to ask one question, so he asked Duch where his wife was killed. A tearful Duch was unable to say.

Chum Mey never found his photo either, only a copy of his confession and a list of prisoners. Next to his name was a note: "Keep for a while."

His wife also remained alive until 7 January 1979, when Vietnamese troops captured Phnom Penh, signalling the end of the Khmer Rouge's grip on the country. The events caused panic at S-21 and the guards took their prisoners and fled into the suburbs to await orders. Here Chum Mey was reunited with his wife and newborn son.

But only he survived the fighting between the Khmer Rouge and opposition forces.

He had already lost his three-year-old son to fever during the forced evacuation of Phnom Penh in 1975. His two daughters disappeared while he was in S-21.

Bou Meng and Chum Mey both remarried and have new families. Chum Mey's grandchildren are playing in the prison courtyard as we talk.

"Visiting every day brings me closer to the victims in those photographs," he says. "I feel their presence here and our responsibility to tell the world what happened."

Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge

Pol Pot leading a group of his men in the 70s

1968 Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge launches an insurgency aiming to return Cambodia to "Year Zero" and build an agrarian socialist utopia.

1973 - 1974 Khmer Rouge controls most of Cambodia - city-dwellers are forcibly moved to the countryside.

April 1975 Khmer Rouge captures the capital, Phnom Penh.

1976 The regime divides citizens into three categories, which determine their food rations. Urban residents, land owners, former army officers, bureaucrats and merchants fall into the "undeserved" category and face execution, starvation and hard labour. All religion and money is banned.

January 1979 Vietnamese armed forces and the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation capture Phnom Penh. Pol Pot flees.

15 April 1998 Pol Pot dies in Cambodia on the day it is announced that he will face an international tribunal. He is swiftly cremated, prompting suspicions of suicide.

2009 Kaing Guek Eav, known as Comrade Duch, is the first Khmer Rouge leader to face the UN-backed Khmer Rouge Tribunal. He is sentenced to 35 years in jail, later extended to life.

2014 - Two more Khmer Rouge leaders, Nuon Chea and Kheiu Samphan, are sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.