Charleston shooting: Attack at church opens old wounds

- Published

Past and present: The black community turns to religion in the face of tragedy

The struggle for black equality was not just a social revolution. For many it was a religious crusade. Throughout, the church was central.

During the height of the civil-rights era black churches echoed to the anthems of the movement, their pews crammed with protesters ready to stream from the doors and out onto the streets.

They also offered a refuge, a sanctuary from the hate-filled segregationist communities that demonstrators were determined to change. Sometimes, church doors remained firmly closed, to protect those inside from the mob outside.

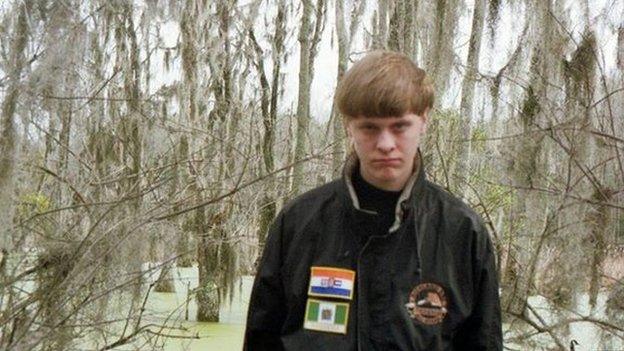

That is partly why Charleston has been so shocking and injuring. In black communities especially, it has reopened so many wounds from history.

Instantly it recalls one of the most grotesque crimes of the 1960s: the Sunday morning in September, 1963, when white supremacists bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

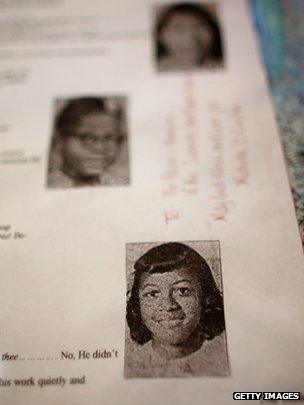

Four girls were killed when white supremacists bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Alabama in 1963

Back then, in a city dubbed "Bombingham" because of the frequency of racial attacks, the weapon of choice was dynamite. Four black schoolgirls were pulled dead from the rubble. Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley are names seared into America's troubled racial narrative.

Only days before the bomb attack, Martin Luther King Jr had delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. The attack on the 16th Street church felt then like a violent riposte.

The church had served as the focal point of demonstrations in the spring, infamous for the snarling police dogs that lunged at young protesters and the fire hoses that were trained on small children with the power to rip bark from the trees.

Cynthia Wesley, 14, was among the victims

The deaths of those four girls helped mobilised white support for the civil-rights bill passed the following year that led to the dismantling of southern segregation.

Though it was never the intention, churches have become monuments to the freedom struggle.

There is the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, which was besieged at the height of the freedom rides crisis in 1961 by an ugly white mob, some 3,000 strong, that wanted to burn it to the ground. King was holed up inside, so, too, the freedom riders who had been rescued from a racist mob at the Greyhound bus station earlier on.

Or there is the Browns Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama, which was the starting point for the march to Montgomery.

Then there is the Mason Temple in Memphis, where King delivered his final speech, the "I've been to the Mountaintop" oration in which he seemed to predict his violent death the following day.

Civil-rights demonstrators in 1965 started an historic march at Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama

King's early emergence as a civil-rights leader spoke of how heavily the movement relied on the church.

When in 1955 the black seamstress Rosa Parks was arrested in Montgomery, Alabama, for refusing to relinquish her "whites only" seat at the front of a bus, local blacks thought a preacher should head up their bus boycott.

They picked a new arrival, who at that time was not particularly well-known locally, let alone famous nationally: Martin Luther King Jr. After the 381 bus boycott came to its successful end, King founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the SCLC, which sought to harness the enormous power and network of the church.

Preachers by no means monopolised the leadership of the civil rights movement, an amalgam of often competing organisations. Groups like SNCC were lead by students, while the NAACP at that time was headed up by Roy Wilkins, a professional activist who focused on the minutiae of the law rather than passages from the Bible.

But churchmen like Ralph Abernathy, King's best friend and loyal deputy, and Fred Shuttlesworth, a hero of the Birmingham campaign, were prominent.

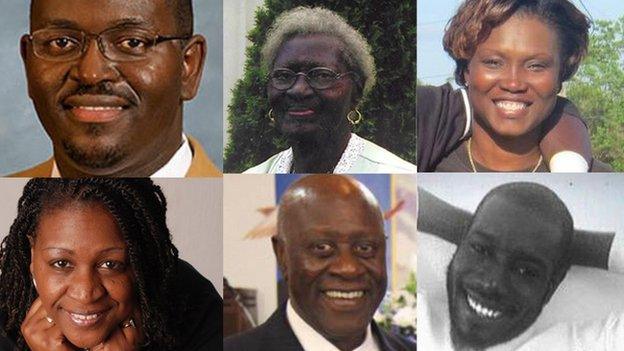

Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, is one of the oldest black churches in the US

Black churches not only provided leaders for the struggle, but moral weight, the faith-based certainty that black lives could be made better and the power of the pulpit.

How many spines were stiffened after hearing King deliver one of his mesmerising sermons? How many white minds were changed when preachers pointed to the scriptures to argue for an end to racial apartheid? How many consciences were pricked when black preachers spoke with such faith-based certainty?

And at a time when white segregationists tried to portray civil rights activists as radicals and communists, the presence of so many preachers automatically gave the movement authority and respect.

Few churches in America have such a rich history as the Emanuel AME Church. It reaches back to slavery, the original sin that America is still contending with. The events of the last 24 hours have felt like revisiting episodes from that baleful past.

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015

- Published19 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015