Inside Tadmur: The worst prison in the world?

- Published

When Islamic State seized Palmyra in Syria last month, one of the first things it did was blow up the Tadmur prison - the country's most notorious jail, where for decades, political dissidents were detained and tortured. The BBC's Soumer Daghastani looks back at its history.

Westerners know Palmyra for its ancient Greco-Roman ruins, but the Arabic term for the place, Tadmur, gives most Syrians goose-bumps.

It's synonymous with death, torture, horror, and madness.

The prison was built by the French in the 1930s, in heart of the desert, about 200km northeast of Damascus. But it was during Hafez al-Assad 30-year rule between 1971 and 2000 that it gained its current reputation. Thousands of political dissidents were reported to have been humiliated, tortured, and summarily executed there.

"It's utterly unfair to call it a prison. In a prison you have basic rights, but in Tadmur you have nothing. You're only left with fear and horror," says Palestinian writer Salameh Kaileh, who spent two years there, from 1998 to 2000, accused of opposing the goals of the revolution that brought Assad's Baath Party to power.

The arbitrary detention and brutal treatment of political prisoners at Tadmur began in the 1970s, when an opposition movement started gaining momentum.

Led by the Muslim Brotherhood and several secular parties, activists demanded political representation and the rule of law. The Muslim Brotherhood grew in popularity and its armed wing carried out acts of political violence against the army and the Assad regime.

But in the late 70s and early 80s thousands of supporters of leftist and Islamist groups were arrested.

Many were executed or died under torture. The lucky ones spent three or four years in prison. Some were there for 20.

Tadmur, beyond surrealism

High walls of cold cement

Control towers

Mine fields

Check points

Barricades and special military forces

Finally… A space of pure patriotic fear

If the whole of Syria falls

This prison will never ever fall

By Syrian poet Faraj Bayrakdar, who was in Tadmur from 1988 to 1992

The bloody massacre that took place within Tadmur's walls in 1980 is ingrained in Syria's consciousness. A day after a failed assassination attempt on Hafez al-Assad, members of the infamous Defence Brigades, headed at the time by Assad's brother, Rifaat, flew from Damascus to Tadmur by helicopter. Soldiers went from cell to cell, shooting prisoners with machine guns.

No-one knows exactly how many were killed but a 2001 Amnesty International report estimates that 500 to 1,000 people were murdered in just a few minutes - most of them were members or suspected supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood.

It's said their bodies were dumped in a mass grave outside the prison.

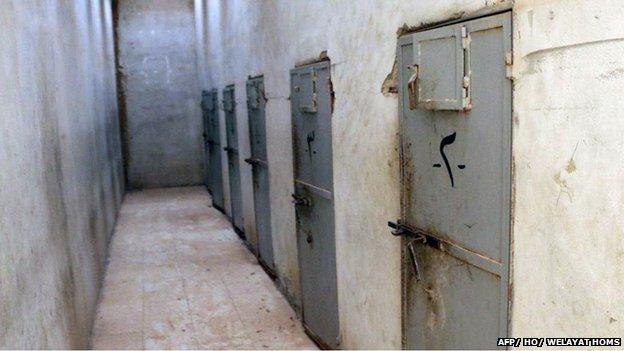

The prison was constructed in the style of a panopticon, a circular building where prisoners in their cells could be constantly watched by guards. The term comes from Panoptes, a mythological Greek giant who had 100 eyes.

Former prisoners told Amnesty that the prison had seven courtyards, 40 to 50 dormitories and 39 smaller cells. There were also 19 disciplinary underground cells that were used for solitary confinement.

"All dormitories had windows covered with barbed wire in the ceiling, allowing guards to keep inmates under constant surveillance," says Kaileh.

"We did not know if the guards were up there watching us or not. But no-one would dare to move from his spot or even raise his head as the consequences would have been dire."

Inmates were not allowed to raise their heads, look up or look at each other.

"I have not seen the eyes of any of my inmates and none of them saw my eyes until after we left the prison. Eye contact was absolutely forbidden," said Syrian writer Yassin Haj Saleh in his article, The Road to Tadmur - he was there from 1995 to 1996.

"We used to distinguish guards from the colour of their boots as we never saw their faces," says another Syrian writer, poet Faraj Bayrakdar. "The guard with black boots is nice but the one with green boots is merciless."

After their release, it was years before some prisoners were able to make eye contact with anyone.

Torture was a daily ritual - a lengthy journey of pain and slow death.

"When death is a daily occurrence, lurking in torture, random beatings, eye-gouging, broken limbs and crushed fingers… wouldn't you welcome the merciful release of a bullet?" wrote one former prisoner in a memoir smuggled out of Syria in 1999.

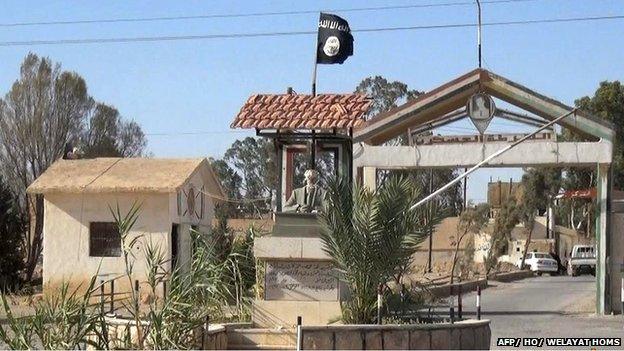

The entrance to Tadmur prison - the IS flag has been placed in the statue of Hafez al-Assad

Former inmates often talk about their first hours at Tadmur and the so-called "reception party" - an initial session of torture that prisoners endured upon arrival.

"The warders pulled us off the bus whipping us mercilessly and brutally until we were all out… the military police searched our clothes and one by one we were put into the tyre [forced to get inside a car tyre] and each person was beaten between 200 and 400 times on his feet," a former detainee told Amnesty.

"Everyone was in a bad condition, their legs bleeding and covered with wounds, as well as other parts of their bodies. Some of the prisoners died during the reception party," he said.

Detainees talk about being humiliated, whipped, and beaten throughout their time there.

"Jailers were given an open licence to do anything, even to kill. Your life was simply worth nothing," says Kaileh.

Military officers were innovative in finding new methods to humiliate prisoners. Kaileh says they resorted to strange and sick forms of torture, sometimes just out of boredom. One night the guard, looking from the ceiling window, ordered him to move all the slippers in the dormitory, about a hundred pairs of them. He told him he could only use his mouth. He had to keep moving the slippers in this way all night.

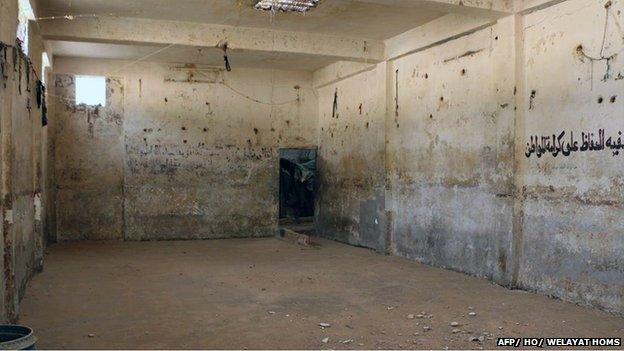

A dormitory at Tadmur - the writing on the right reads "To preserve the dignity of citizens"

Others talk about an incident when two prisoners were forced to hold an inmate by the hands and feet, rock him high in the air, and then fling him away to fall on the ground. One prisoner who refused to do so was beaten around the head and died a month later.

Inmates would cry out for medical help for dying prisoners. The guards' answer was always the same: "Only call us to collect bodies."

"Tadmur is a kingdom of death and madness. The fact that such place existed is a shame, not only on Syrians, but on all humanity," says Bayrakdar.

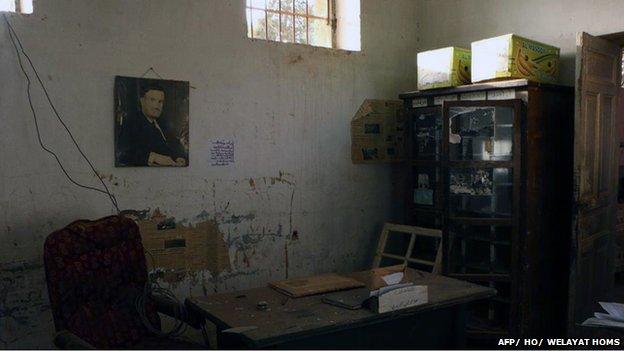

When IS captured the building, it released pictures of the inside. Apart from the guards and detainees who lived to tell the tale, no-one had seen inside its walls before.

But the destruction of the building came as a shock for many who wanted it to stand as a witness to years of brutality.

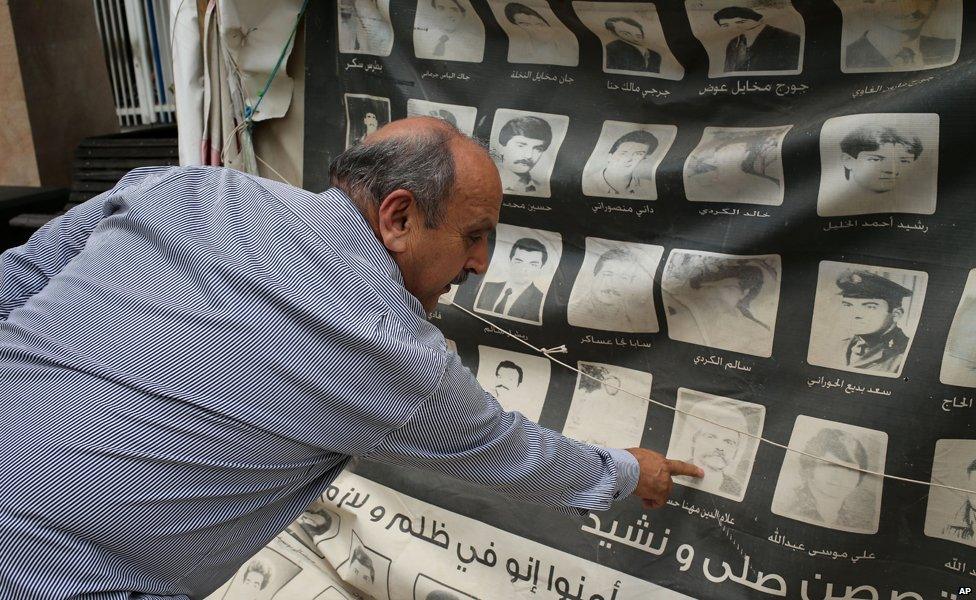

Ali Aboudehn points to a portrait of a fellow inmate who is now missing

"IS demolished a historic symbol that should have stayed, because in every room there were people who were killed," Ali Aboudehn, a Lebanese man who spent four years there, told AP.

Yassin Haj Saleh said he felt as if his home was destroyed. "I dreamt that I would visit it someday... This visit would redeem me... it would be a closure… The destruction of a prison that was the symbol of our slavery is the destruction of our freedom," he posted on Facebook. He considers the act of blowing it up "a huge service to Assad's regime of slavery".

The remains of Tadmur

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.