Charleston shooting: Race, rage and the American condition

- Published

As Charleston mourns, Mayor Joseph Riley Jr reflects on the character of the city

After the shootings, Charleston's beloved mayor struggles with an ugly reality of racism and rage. Yet his campaign to combat inequality shows how big the problem is - and how small some solutions can feel.

Mayor Joseph Riley Jr, speaks eloquently about British architecture and the history of Charleston.

When asked about Dylann Roof, the 21-year-old from Eastover who's been charged with nine counts of murder, though, he struggles.

"We had the tragic misfortune of this evil person committing this act who came from a distant town," the mayor says.

"It's like almost like an alien source appeared here," he says. "It's not this city."

His language reflects his personal anguish over the massacre in Charleston, a place of beauty and charm.

His response is understandable - and common.

Just as he says the assailant is from somewhere else, so do people in New York, Washington and other Northern cities try to push away the notion of racism and extremism.

Oh, that's in the South, they say.

Perhaps now after this particularly brutal act in Charleston, it's time to take stock of what's happening.

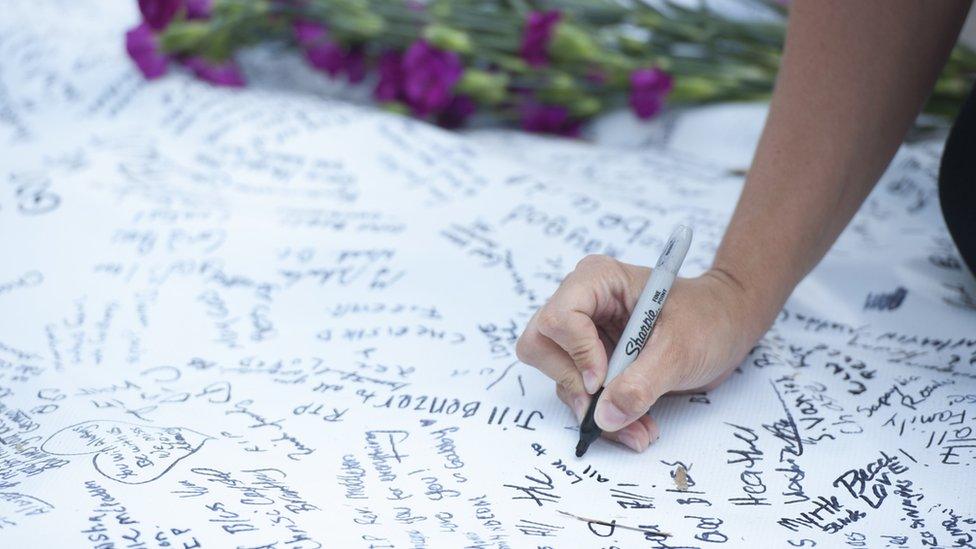

A condolence sheet was filled with tributes

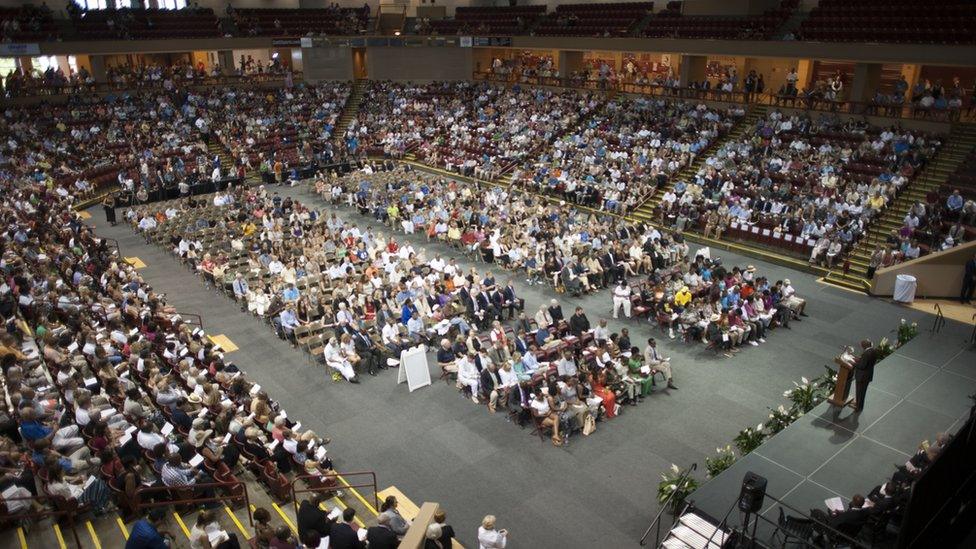

A show of unity in Charleston

These shootings come as the conversation about racial injustice in America has become increasingly heated, with a continuous series of unjust police encounters, deadly assaults, inhumane prison treatment and burdensome legal fees symbolising a structural racial injustice

Taken together these events make it harder to say violence against African Americans is random or confined to another place, wherever that may be.

They also make the portrayal of Roof as an outsider, at least according to New York University's Charlton McIlwain, seem "disingenuous".

McIlwain has studied race for years, and he tells me platitudes and kind gestures from those in power will only get us so far - especially if they come at the expense of structural change at institutions and in federal and state policies in the US.

Cal Morrison, a retired security-systems manager in Charleston, agrees. Wearing a black "Do you believe us now?" T-shirt, Morrison says Roof and his racist violence is hardly alien.

"It is us," Morrison says. "It is part of our culture from the vestiges of slavery."

Two days after the shootings, the mayor heads for Emanuel AME Church. Paint is peeling from the spire, showing splotches of charcoal-grey, and the stained glass windows are dark.

Someone puts a tulip near a sign that says:

<italic>Rev Clementa Pinckney Pastor Sundays at 930 AM</italic>

It's a makeshift memorial for him and Ethel Lance; Sharonda Coleman-Singleton; Depayne Doctor; Cynthia Hurd; Susie Jackson; Tywanza Sanders; Daniel Simmons, Sr and Mira Thompson.

A balloon tied to a flowerpot says: "Officially the best dad ever". A teddy bear sits with its head slumped on its chest.

Riley, 72, is wearing a striped tie and a light-beige, cotton jacket ("Charleston uniform", says one of his aides). Despite the 90F degree (32C) he looks cool while he talks to journalists.

Unlike them, he doesn't have damp splotches on his shirt. His shoes are rust-coloured, and the leather looks as soft as butter.

He says he once marched "on these two feet" from Charleston to Columbia, the state capital, to protest against the Confederate battle flag over the statehouse.

Joseph Riley led protests against the Confederate flag over the state's capitol in 2000

At that time, it flew directly over the capitol dome. As a compromise, it was moved to the grounds directly in front of the statehouse.

The march, which covered 120 miles and took place more than a decade ago, is one of the reasons he's beloved. A progressive, he talks about gun control and race issues and has helped build the city's award-winning parks and market squares.

He decided to run for mayor, he says, because he wanted "to build a bridge between the black and white community".

He was elected in 1975 and afterwards went on a trip to Europe, spending time in England.

In Bristol he saw a park built with big, new trees rather than small ones and with granite instead of concrete.

"I understood that you don't apologise for using good materials," he says. "If you're going to build something for citizens, then you build it with great beauty."

The parks, he says, are for everyone, "poor and rich, black and white," saying they have "enriched our city emotionally".

The city has a dark past - and much to overcome. Nearly half of the slaves in the US who arrived on ships came through Charleston.

More recently the city's Emanuel AME Church served as the centre of the civil-rights movement. Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jr spoke there in 1962.

As Riley moved into the mayoral office schools were being integrated, and discriminatory policies abolished.

"There was change in America," he says. "I realised the South needed to change."

Keith Waring, 59, a city councilman, says the mayor has over the years helped bring together blacks and whites and is known for his "open-door policy" for civil-rights activists and others.

The mayor appointed the first black police chief, Reuben Greenberg, a pioneer in community policing, in 1982, and has worked to foster better race relations.

The New York Times' Frank Bruni says Riley is, external arguably the "the most loved politician in America".

That afternoon Riley sits in a wooden chair in a second-floor room at city hall. He points to an oil painting of an African-American civil rights activist, Septima Poinsette Clark, and says once the room had portraits only of white people.

Because of his efforts, he says, her portrait along with one of Daniel Joseph Jenkins, an African American who founded an orphanage, are now on the wall.

Later I count the paintings - 27. Two portraits of African Americans are better than none, but it hardly seems like sweeping reform.

Riley grew up about a mile from city hall. When he was little, he used to buy wildflowers from an African-American family who had a stand across the street from the building.

Sheila Taylor, 62, now sells sweet-grass baskets, the kind slaves made when they laboured in the fields, on the same corner.

"He's a very nice man," she says, describing the mayor. "He's been good to the black people."

Her baskets cost $70 (£44) apiece, more than wildflowers. Otherwise little has changed.

He's chosen to do things incrementally, and the results are modest. At times he comes across as a kind-hearted plantation owner, a man overseeing a system that, while functioning, is deeply flawed.

"To his credit he has put race relations at the forefront," says McIlwain. "But his failures are symptomatic of how entrenched racism is in Charleston and elsewhere."

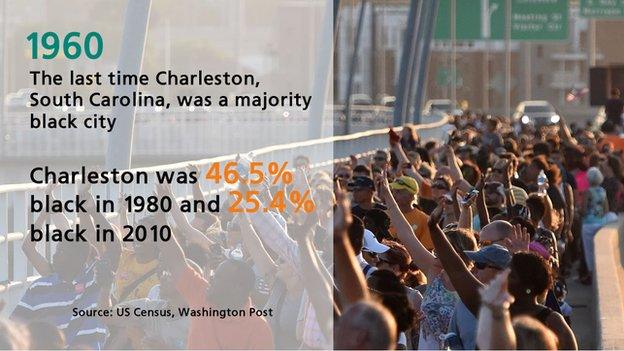

The number of blacks living in Charleston has gone down over the years. Activists and city officials say many have been driven out by high prices and by wealthy, white residents who are buying up property.

For many of those who remain, poverty, unemployment and homelessness remain a serious problem.

The shootings in the church reflect the rage, violence and racism that lurk below the surface, exposing a wound.

However you try to understand its reasons, one thing is clear - the pain has permeated the city.

"Every heart is broken," Riley says. "White people, black people, everybody is mourning."

That evening he sits in a large auditorium near the church. People are carrying long-stemmed roses. Hundreds of them were de-thorned and donated by a florist in New York.

Outside it smells like sandalwood, wafting from an incense stick someone has stuck in the dirt.

Inside an African-American activist, J Denise Cromwell, 52, holds a sign about justice. She runs a barbershop and a homeless programme and knows about the challenges the mayor faces.

"His work is a very difficult task," she says.

She says she isn't convinced by his claim that the assailant is from a distant land, though, a place the mayor says lies "a two-hour drive" and "almost 100 miles" away.

"The real truth is it ain't somewhere else," she says. "We got to face it here."

As she talks, a young white woman in a ponytail comes over and puts her head on her shoulder. "My daughter," Cromwell says.

I look at them, puzzled.

Cromwell recalls how she saw the woman, Asia Cromwell, who's now 24, as a three-day-old baby in a hospital. Her birth mother was unwilling or incapable of caring for her, says Cromwell, who decided on the spot to adopt her.

"I really didn't see the colour," Cromwell says. She swirls her hand in the air, showing how it seemed to disappear.

Since the shootings in the church, people in Charleston, including those who lost loved ones, have spoken of forgiveness. It's an extraordinary gesture, but not everyone thinks it's the right path.

The mayor, for one, says he can't muster it.

"I don't know that this man can be forgiven for what he did," he tells me. "I don't know that I can do that."

On this point McIlwain agrees. He believes people in the US have tried for too long to overcome racism simply by striving for greater love and kindness between blacks and whites.

"You hear, 'It's time to heal,' and, sure, I'm all for that. But I think it's not the cure," he says.

For change to occur, he says, political and economic institutions must be reformed.

Some things have happened. The Confederate flag - the one Riley protested about years ago - may soon come down.

Governor Nikki Haley says it should be taken from the State House building. Lawmakers are considering steps for its removal.

And while not everyone is ready to forgive, they're trying to look ahead.

"You know few cities have escaped their histories unscathed, and this is one of those brutal injuries that this city is experiencing," Riley says. "But our people know that you move forward."

Like others, he'll carry on with his work.

For the event in the auditorium he's changed into a dark suit. He sits near the podium as church leaders talk about the dead.

During the speeches he wipes his face with a handkerchief. It's near the end of a long day, one so draining even he has started to sweat.

Photographs by Colm O'Molloy