When the UK was bombed nightly for eight months in a row

- Published

Burning building in Manchester after a German air raid, December 1940 (© IWM)

In early World War Two - from autumn 1940 to spring 1941 - German bombs killed 43,000 people across the UK. As the 75th anniversary of the start of the Blitz approaches, Imperial War Museum North has a new exhibition.

Horrible Histories: Blitzed Brits, external looks at how the bombing came about - and the devastation and death that was caused in the nightly raids.

In the quiet early months of the war people in the UK prepared for air attacks by Nazi Germany, says Ian Kikuchi from the Imperial War Museum. But domestically there were few signs that Hitler's bombers would soon be based just across the English Channel.

Then in spring 1940 the Germans invaded France and the Low Countries. Later in the summer the German air force, the Luftwaffe, tried to gain air superiority in the skies over the UK in the Battle of Britain.

Evening newspapers announce Germany's invasion of Poland, September 1939 (© IWM)

But it was the resilience of the Royal Air Force during that "Spitfire summer" that caused the Germans to revise their plans, says Kikuchi - and on 7 September 1940 they embarked on a sustained eight-month bombing campaign, targeting all the UK's major cities.

22 December 1940: Buildings in Manchester Piccadilly on fire after German air raids (© IWM)

The Germans tried to disrupt imports of food - and docks in places like Plymouth, Liverpool, and Belfast were targeted.

News report showing the Blitz

On the ground, people would have heard the drone of the engines of German aircraft - waiting for high explosive bombs to drop, some weighing up to 2000kg.

St Paul's Cathedral survives the Blitz, December 1940 (© IWM)

London in particular, says Kikuchi, was bombed for 57 nights in a row between September and November 1940.

Daytime photograph of Manchester after a German air raid (© IWM)

Up to 10% of bombs did not explode on impact. The small hammer pictured below was used by bomb disposal teams to dislodge fuses.

Unlike iron or steel, its brass head was less likely to create sparks or a magnetic field.

Blitz bomb disposal hammer (© IWM)

As well as RAF sorties, the British military used gas-filled barrage balloons to deter the Luftwaffe, with searchlights piercing the night sky, and ground-based anti-aircraft weapons - like the Swedish-designed Bofors gun - firing up at German bombers.

Bofors gun in action (© IWM)

The anti-aircraft weapons caused other issues though. Kikuchi says there is an account of one London council calling for the guns to stay silent - as the vibrations they caused when fired were blamed for breaking toilet bowls in council-owned homes.

Air Raid Precautions workers - and Rip the dog - search rubble in Poplar, London, 1941 (© IWM)

To make it more difficult for the Germans to spot cities at night, strict blackout restrictions were imposed. Homes covered their windows to stop light from seeping out, streetlights were dimmed and car headlights were reduced to small slits.

But in the night sky, with moonlight shimmering on river estuaries, certain cities like London, Liverpool and Hull were easier to spot.

Civil Defence Warden in Holborn, London (© IWM)

The colour photo above shows an air raid warden surveying bomb damage in central London. Kikuchi says the wardens were a key figures civil defence service - each given a few streets to look after.

They reported damage, educated local residents and kept detailed records of where families usually slept at night - and what kind of air raid shelters they had.

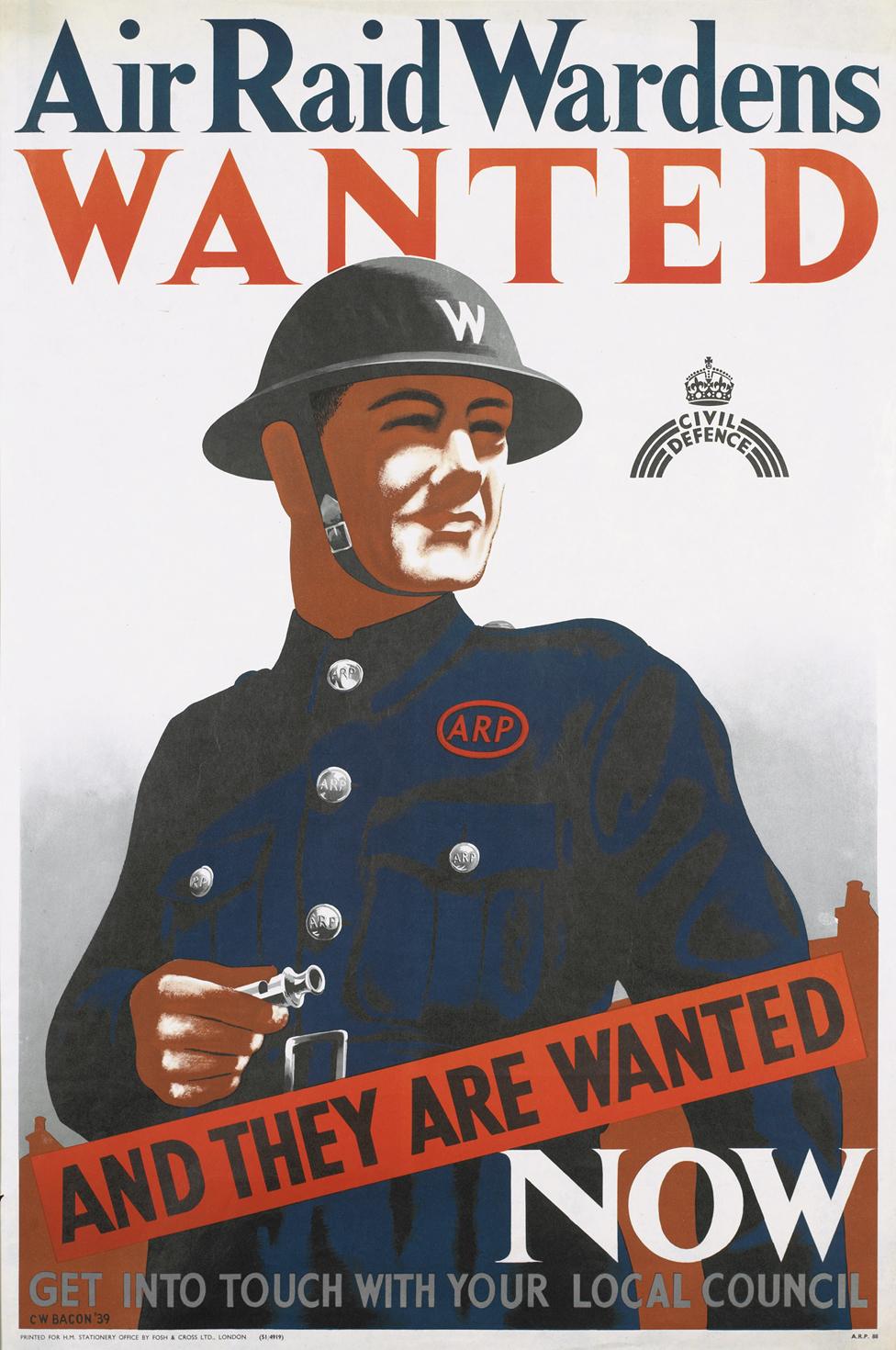

Government poster (© IWM)

Depictions of air raid wardens as pompous and power-crazed - like Warden Hodges in the BBC sitcom Dads Army - are not necessarily fair, says Kikuchi. He says many of them were public-spirited individuals wanting to do their bit for the war effort.

The job also offered steady employment, he says. By the summer of 1940, he says, more than 600,000 people were employed in air raid precautions work.

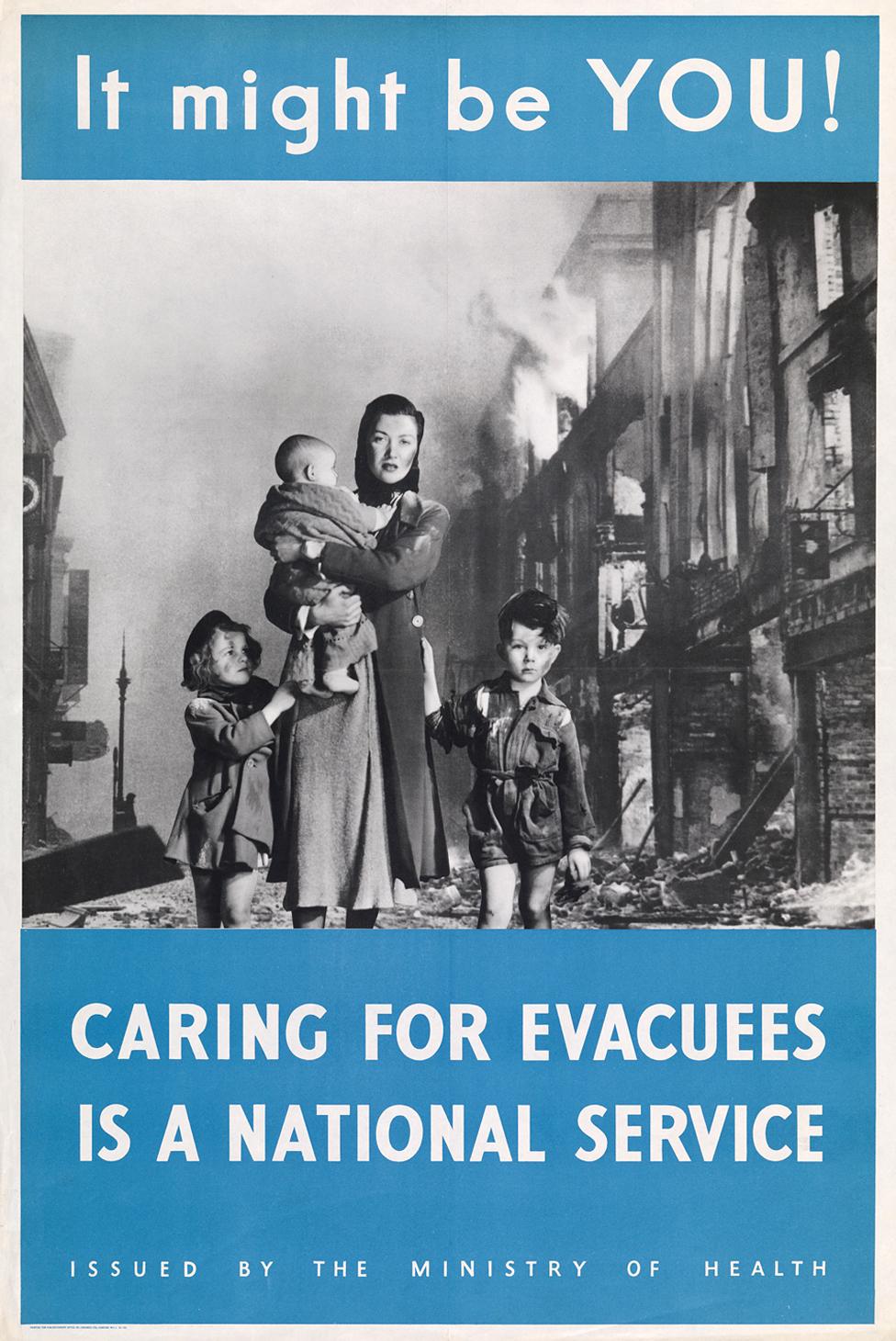

Government poster (© IWM)

To escape the bombs, more than a million children, thousands of young and expectant mothers, and some disabled people were evacuated to the countryside.

Kikuchi says for the city evacuees - and those in the country who took them in - there was often a culture shock, as two worlds collided.

Large scale evacuation began on the eve of the outbreak of war in 1939 - but when the expected air raids on cities did not happen, many evacuees returned home.

Once the bombing began in earnest a year later, there was a second wave - and some children ended up being sent overseas to North America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

Sister and brother, June and Tony Bryant, waiting for the train at Clerkenwell Station which evacuated them from London to Luton (© IWM)

When war broke out in 1939, there was a real fear that poisonous gases, like those used on the battlefields of World War One, would be inflicted on the civilian population during air raids.

Gas masks were issued to everyone - but some manufacturers saw a commercial opportunity to protect family pets. This next image shows a gas-proof dog kennel.

Gas-proof dog kennel used in the Blitz (© IWM)

But despite everything that was done to protect people and to confuse the Luftwaffe - from mass evacuations to the blackout - the German bombing campaign on the UK from late 1940 into 1941 was devastating. Buildings and homes were destroyed. Thousands of people lost their lives.

This image - from 23 December 1940 - shows fire crews tackling a blaze in a bombed warehouse in Manchester. The city experienced two nights of heavy bombing just before Christmas.

Manchester, December 1940 (© IWM)

Nightly scenes like this were repeated across the country - and when morning came, ruins were on show for all to see.

This next photo shows piles of rubble in Coventry on 16 November 1940, the day after the bombing raid which also knocked the heart out of the city's 14th Century cathedral.

Blitz damage in Coventry, November 1940 (© IWM)

In May 1941, Hitler turned his attention to the Eastern Front - and domestically, says Kikuchi, there was a sense that Britain had weathered the worst of what the Luftwaffe was able to inflict.

But although the Blitz accounts for more than two-thirds of the 60,000 or so civilian WW2 deaths - the deadly attacks continued sporadically.

In summer 1944, after the D-Day landings in Normandy, the Germans launched their vengeance weapons - V1 flying bombs and then V2 rockets.

This final image shows a police officer comforting a man whose home in south London was destroyed in a V1 bomb attack.

The man had taken his dog for a walk on a Saturday afternoon. He returned to find his house destroyed, and his wife - who had been inside making dinner - killed.

Upper Norwood, London, 1944 (© IWM)

Horrible Histories: Blitzed Brits, external can be seen at IWM North, part of Imperial War Museums, in Manchester until 10 April 2016.

All images and video subject to copyright.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.