The US-UK divide on sex cases

- Published

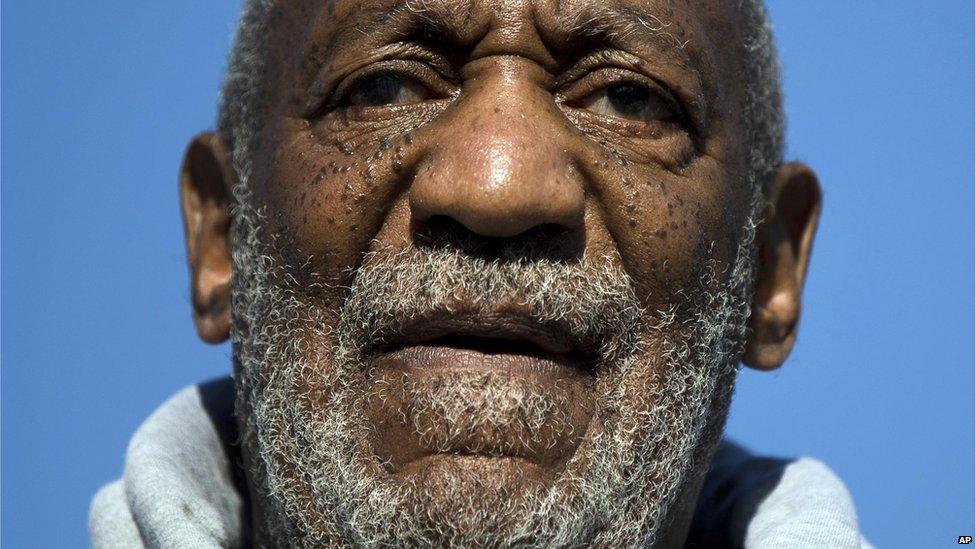

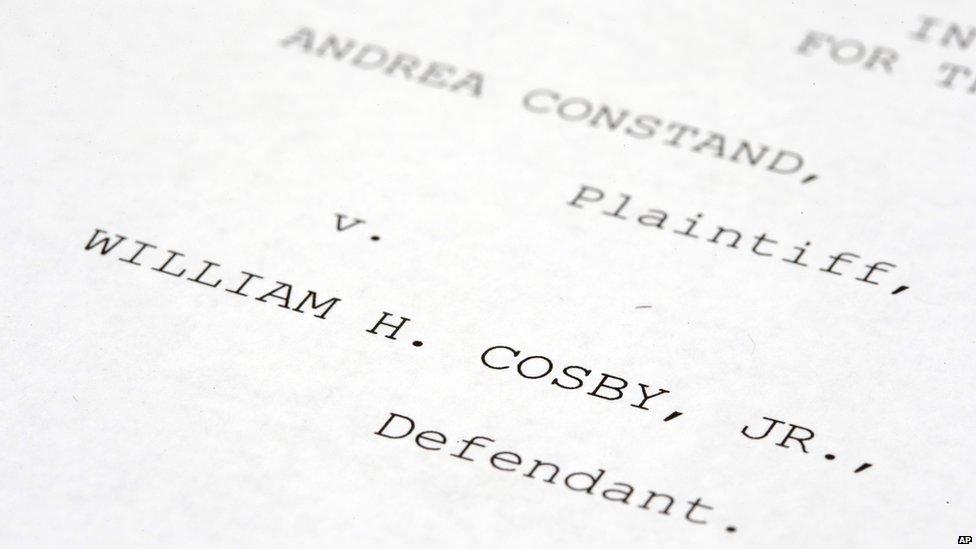

Bill Cosby faces a string of allegations of sexual assault but cannot be prosecuted in the US because of the statute of limitations. In the UK there is no time limit in sexual abuse and other serious cases. What explains this difference?

The statute of limitations is effectively an expiry date for allegations of crimes. And that expiry date varies from state to state in the US.

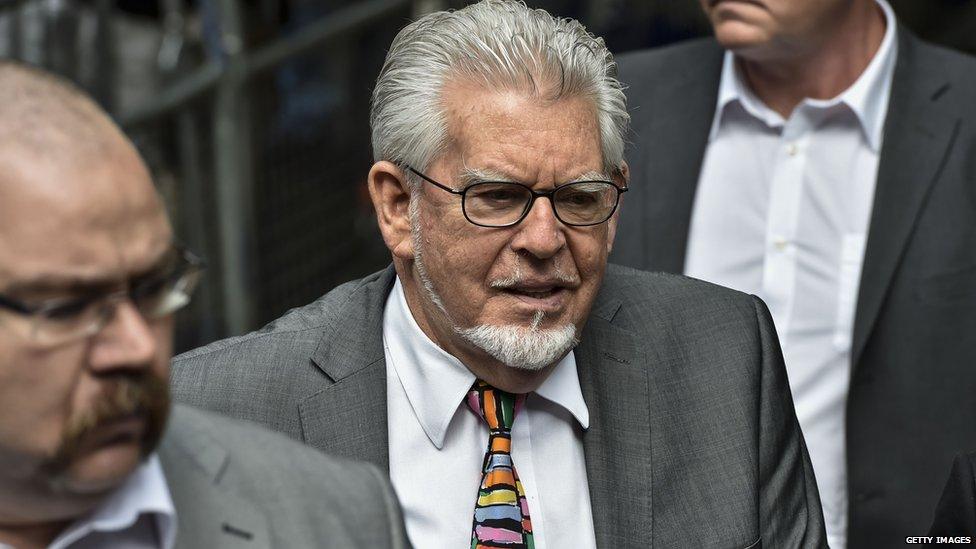

In recent years in the UK, there have been a number of high-profile prosecutions of historical sexual abuse cases. Entertainer Rolf Harris was jailed last year for offences that took place between 1968 and 1986. Broadcaster Stuart Hall was jailed in 2013 for offences between 1967 and 1985. TV weather presenter Fred Talbot was jailed this year for offences that took place in 1975 and 1976.

Labour peer Lord Janner is currently facing criminal proceedings relating to 22 allegations of sexual abuse against nine children during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

But in the US the law in most states is typically very different.

In the Cosby case, many of the accusations date back to the 1970s and 1980s - too long ago in the eyes of the law. Only one woman's allegation against Cosby falls within the time limit - that of Chloe Goins, who claims she was drugged and sexually abused in 2008.

Chloe Goins (left) claims she was assaulted by Bill Cosby in 2008

Thirty-four states have statutes of limitations, external - with time limits from three years to 30 years. Taking the example of the offence of rape, the three bordering states of Georgia, Florida and Alabama highlight just how uneven the law can be.

Georgia has a limit of 15 years. Victims in Florida must bring their case within four years. But there are no limitations at all across the state border in Alabama.

Some states do make exemptions if a DNA match is found many years later - although even these can carry time limits.

But even if a perpetrator walks straight into a police station and confesses, there's no guarantee of prosecution.

Bart Bareither did exactly that in Indiana last year. He confessed to raping Jenny Wendt nine years earlier. Wendt hadn't reported the crime as she didn't have DNA evidence to prove it and didn't trust that he'd spend a day in prison.

And despite Bareither's confession, he won't. Indiana's statute of limitation on rape is just five years.

Since then Wendt has successfully campaigned to change the state's law - now known as "Jenny's Law", external - to allow later prosecution if there's DNA evidence or a confession.

Most of Europe also imposes limitations for sexual abuse proceedings.

Dominic Strauss-Kahn avoided prosecution for sexual assault in 2011

In France the limit is 10 years for attempted rape. Ex-IMF chief Dominic Strauss-Kahn was a high-profile beneficiary of these limits in 2011.

Writer Tristane Banon had claimed that Stauss-Kahn tried to rape her in 2003. Although within the 10-year limit, prosecutors found there was insufficient proof to prosecute for attempted rape. But they did find "facts that could be described as sexual assault".

But the statute of limitations for sexual assault is only three years - so the case was dropped.

Swedish prosecutors wanting to question Wikileaks founder Julian Assange over rape accusations were forced to change their strategy in March because some of the potential charges against him would "expire" in August.

Julian Assange (right) has been sheltering in the Ecuadorian embassy in London for three years in order to avoid questioning over rape accusations in Sweden

The fundamental principle of a statute of limitations is to protect the defendants.

The notion dates as far back as ancient Greece, explains Penney Lewis, a law professor at King's College London. There are two main reasons behind it, she says.

One is that there should be some finality, so that a person can move on with their life without the constant threat of prosecution hanging over their heads, Lewis says.

The second is about ensuring a fair trial for the defendant, she adds.

"There's a practical matter - it becomes so much more difficult to prosecute cases that occurred years and years ago," says Jennifer Temkin, law professor at City University London. "Memories can fade."

Exonerating evidence for a defendant may well have gone missing after several decades, for instance.

In some contexts it makes sense to put an expiry date on a crime, Temkin says.

Indeed statutes of limitations do exist in the UK for minor criminal cases and in many civil claims. In the field of sexual offences, there is one limitation - for "unlawful sexual intercourse" offences that took place between 1956 and 2004. This refers to cases of supposedly consensual sex with children between the ages of 13 and 15, where a case must have been brought within a year. Historical cases of this offence therefore cannot be prosecuted now.

Despite the UK's general lack of statutory limitations on prosecuting historical sexual abuse cases, many were still dropped before trial, says criminal barrister Kama Melly.

Before the 1990s, judges often used to throw out historical sex abuse cases because they questioned whether it was fair for the defendant to stand trial, Melly says.

The UK and the US are predominantly common law systems, which means they tend to evolve organically and gradually through case law, explains Melly.

It also leaves a lot more discretion in the hands of judges - unlike most European law systems, which adhere to much stricter codes for specific crimes.

The US is rare among common law jurisdictions in its sexual abuse limitations

Statutory limitations are in fact quite rare in common law jurisdictions, explains Lewis. "The US is actually the outlier," she says. Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and Australia also have no sexual abuse limitations.

The UK judicial system is therefore more flexible than the US on this issue, Melly suggests.

Prosecutors can appeal against a judge's decision, and gradually their judicial discretion to throw out historical sexual abuse cases has been curbed, Melly explains. Judges are very wary of dismissing a case for that exact reason, she adds.

"The strong feeling now is that the jury can take age and delay into account and people can still have a fair trial after a considerable period of time," Melly says.

But crucially, says Melly, this legal evolution has coincided with a wider cultural shift and an increased understanding of sexual abuse.

Empirical evidence shows that sexual abuse cases are especially prone to delayed reporting compared with other types of crime, Lewis says.

Rolf Harris was convicted for offences dating between 1968 and 1986

"Complainants often feel guilty, ashamed, or as though they're somehow complicit in the abuse," she says. "They fear not being believed - and in many cases they're right to fear that," Lewis adds.

Melly mentions a recent case of hers in which the victim waited until her mother had died before making her claim, because she couldn't bear to highlight her mother's failings while she was still alive.

"The current thinking [in the UK] is that it would be very wrong while we've reached a climate where victims feel safe to come forward," Melly says, "to have a system that says, 'I'm sorry, you waited too long to come to terms with this'."

The federal nature of the US makes legal evolution more piecemeal. "The federal government certainly has no appetite to get involved," Lewis says.

Instead it occurs on a state-by-state basis. But there are signs of change.

Aside from Wendt's successful campaign in Indiana, two years ago Kansas doubled the statutory limit, external from five years to 10 years.

More from the Magazine

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.