The great gluten-free diet fad

- Published

Millions of people around the world are giving up gluten. I know why I stopped buying traditional bread and cakes, but I'm unsure about everyone else, writes William Kremer.

This is how to rid your life of gluten. First, chuck out your bread, flour and wheat breakfast cereals. Throw away open jars of jam and tubs of margarine in case they harbour crumbs.

Invite friends to your house to drink all your beer and start taking your own sausages to barbecues (and cook them on a separate grill).

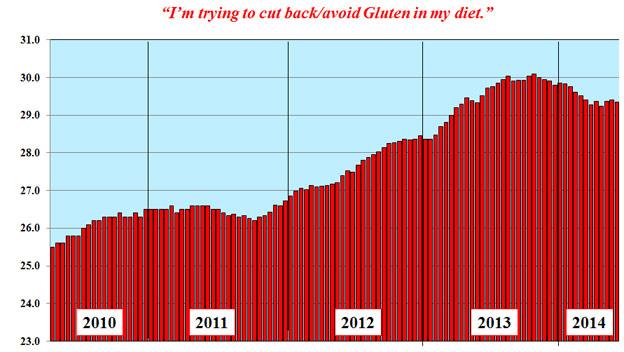

Millions of people are doing all of the above, and probably a lot more besides, as they go gluten-free. Twenty-nine percent of adult Americans - 70 million people - say they are trying to cut back on gluten, according to the market research company NPD Group. In the UK, The pollster YouGov reports that 60% of adults have bought a gluten-free product and 10% of households contain someone who believes gluten is bad for them.

Here's how my own household became one of those 2.6 million homes.

In February, my 21-month-old son Sam went down with what appeared to be a nasty virus. My wife and I set about dealing with the vomiting and diarrhoea, expecting things to improve in a few days.

But as the weeks passed, we began to wonder what kind of virus this could be. Normally a force to be reckoned with at the table, Sam began to pick at his food and lose weight. At bath time we could see the outline of his ribs above his belly, which had swollen up like a balloon.

He stopped walking or even being able to stand, and his sunny personality shaded over. He screamed at strangers and refused to make eye contact or even look in a mirror. Day and night, the house was filled with the sound of jarringly upbeat nursery rhymes playing on a loop from YouTube - watching them was the only thing that seemed to bring him any pleasure at all.

One day, feeling overwhelmed, we went to the hospital emergency department, and it was there that a paediatrician first mentioned an illness that I had never heard of before. I had no idea what coeliac disease was, or even how it was spelled. A blood test and biopsy confirmed that my son had this autoimmune condition that is fed by gluten, a protein. Gluten is found in wheat, and very similar proteins are present in barley and rye. Even a crumb of bread, we were told, was enough to send Sam's body haywire.

Sam, looking anaemic, the day before we removed gluten from his diet. We took him for a final gluten blowout, but he only touched his water.

Sam - and I mean this in the nicest possible way - is an evolutionary throwback. Go back more than 10,000 years and everyone was on a gluten-free diet. Then they started farming - an agrarian revolution that gave our species the free time to build civilisations and develop culture and technology.

Human beings generally have a lot to thank gluten for. It makes our bread light and springy, since it is able to trap steam and carbon dioxide as dough rises, and during baking.

But it is unique among proteins in that it cannot be broken down completely by human beings into amino acids. The best we can manage is to break it into chains of acids called peptides. These simply pass through most people's bodies, but coeliacs are genetically predisposed to flag them up to the immune system, which believes it is being attacked by microbes.

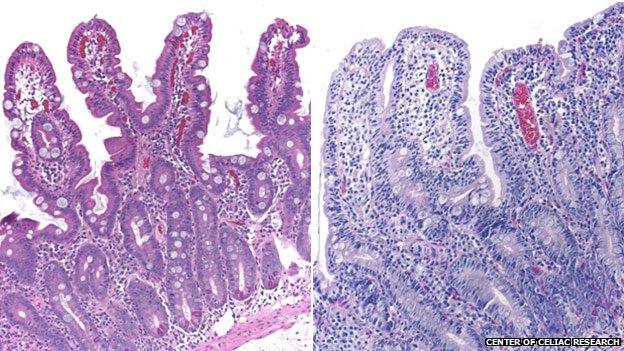

A war begins, and there is collateral damage: a flattening of the villi, the finger-like fronds that line the small intestine and absorb nutrients into the bloodstream. As they become stunted, their surface area decreases and they cannot do their job properly. When the gastroenterologist showed me pictures of Sam's small intestine it was red and inflamed. (I didn't really know what I was looking at, but he assured me it wasn't good.)

Healthy villi (left) and stunted ones in a coeliac sufferer

There are many alarming long-term effects of untreated coeliac disease, ranging from stunted growth to bad skin rashes and - in rare cases - intestinal lymphoma. Worryingly, most people who have it don't know about it and may not even have any obvious symptoms (in the UK only 24% of sufferers are diagnosed). It's unknown why it "switches on" at any given time and there is currently no cure, but there is a simple treatment - steer clear of gluten.

About a week after we started to do this, Sam began to brighten up and put on weight. He gained two kilos in two weeks - the amount children his age typically put on in a year. Before too long, the little boy we had not seen for some months came back.

Coeliac disease is quite common, afflicting about 1% of people in the developed world, but it isn't enough to explain the burgeoning popularity of the gluten-free diet. According to Mintel, 7% of UK adults say they avoid gluten because of an "allergy" or "intolerance" (strictly speaking, coeliac disease is neither of those), and a further 8% avoid it as part of a general "healthy lifestyle".

This view, that gluten isn't just bad for coeliacs like Sam, but for everyone, is endorsed by bloggers, best-selling nutritionists and celebrities. A report on the US gluten-free market by Mintel values it at almost $9bn, because "the health halo surrounding the gluten-free category continues to drive general consumer interest". The singer Miley Cyrus encapsulated the mood in a tweet: "Gluten is crapppp anyway!"

A glance at internet searches over the years suggests that the rise of interest in gluten-free diets has little to do with a growing awareness of coeliac disease, and a lot to do with the popularity of "paleo" diets - the food movement that seeks to return humankind to the Stone Age, at least as far as diet is concerned.

I did my own journalistic hunter-gathering at the Allergy and Free From exhibition in west London, a beacon for all loathers and avoiders of gluten, dairy, nuts and the like. The exhibition was actually a three-in-one, as this year a vegetarian / vegan show and an organic show were bolted on to the allergy exhibition.

"When we were starting to ask the [allergy] audience about other things they were interested in, it turns out we had 40% or 50% vegetarians or vegans coming through the door," Tom Treverton, the event's director, told me. While some of the show's 35,000 visitors would just be looking for niche products to answer their particular dietary need, "there is an emerging trend in the Free From lifestyler - that is the person who wants to cut something out of their diet for another reason - not because they're allergic to it, but because they feel better when they do it, and they think it might be healthier."

The crossover isn't just with organic and vegetarian food. You don't have to wander far past the cakes, beers and salty snacks to find yourself looking at acupressure mats and energy balls. A surprising number of pet charities were also present at the event.

"I didn't think I'd like it, but it's brilliant, so I'd definitely consider it," one woman told me, speaking about the gluten-free diet that my son must follow for the rest of his life. Most people I spoke to, though, had genuine health concerns. I met coeliacs on a mission to find a decent loaf of bread or bottle of beer, but I spoke to even more people who described themselves as "gluten intolerant".

"It's terribly embarrassing to turn up at a social event with swollen lips or a swollen face," said Elizabeth Jones, referring to an intolerance she began suffering from 15 years ago. Gluten was just one of a number of foods that she cut from her diet - the list also included grapes - which, by trial and error, seemed to alleviate her symptoms.

The Allergy and Free From show

Another woman, Debra from Hertfordshire, used to suffer from acid reflux. She was checked for coeliac disease, and found not to have it, but a hospital dietician nevertheless recommended that she cut gluten from her diet. It seemed to do the trick. Debra herself is a paediatric gastroenterology nurse. She told me she saw a large number of children, whose villi were undamaged and therefore got a negative biopsy result - but like her, their condition improved when they stopped eating gluten.

In February 2011, some of the world's leading researchers on coeliac disease met in a hotel near Heathrow Airport in London to discuss patients like Debra, who had many of the outward signs of coeliac disease but few of the inward ones. A report of this meeting, published in the journal BMC Medicine, proposed that doctors broaden their scope from just looking at coeliac disease, to a "spectrum of gluten-related" disorders, with coeliac and wheat allergy (which affects a tiny minority of people) at one end of the spectrum, and "non-coeliac gluten sensitivity" at the other.

The existence of gluten sensitivity remains disputed, but one of the men in the room in 2011, Dr Alessio Fasano, director for the Center of Celiac Research in the US, is a believer. His open-minded attitude is a result of his remarkable experience treating coeliac disease in North America.

In 1993, he took up the post of director of paediatric gastroenterology at the University of the Maryland School of Medicine. He was a young doctor from Naples in Italy, where he had seen perhaps 20 or 30 children a week with coeliac disease.

It was a different story in the US. "The days, the weeks, the months passed by - and I did not see a single case of coeliac. Not a single case," he recalls. In 1996, Fasano published a paper in a paediatrics journal entitled Where have all the American coeliacs gone? The research, based on analysis of 2,000 blood samples that Fasano bought from the Red Cross, contended that there were just as many coeliacs in the US as there were in Europe, but because the disease was so narrowly defined in America, they were being misdiagnosed.

The reception from his peers was sceptical. So Fasano and his team launched a much larger epidemiological study of 13,000 people. This helped shift the estimated prevalence from one in 10,000 to one in 133. His clinic now treats more than 1,000 patients a year.

Dr Alessio Fasano

Unlike wheat allergy and coeliac disease, gluten sensitivity does not have a known set of biomarkers - doctors can't tell if a patient is suffering from it by examination (although there is a blood test, it doesn't give accurate results for many patients). So it can only be diagnosed by first ruling out other diseases and then trying out a gluten-free diet.

Although gluten has no nutritional value in itself, making a radical change to one's diet without the supervision of a dietitian is a bad idea, Fasano insists. "Going gluten-free deprives you of many key elements of the diet, like vitamins and fibres that need to be supplemented in order to maintain balanced nutrition," he says.

Find out more

Gluten-free diets were discussed on Health Check, on the BBC World Service

Health Check is broadcast on Wednesdays at 18:30 GMT

Part of the controversy surrounding gluten sensitivity stems from the fact that it is difficult to disentangle any benefits someone may experience by adopting a gluten-free diet from the placebo effect - the power of a patient's expectation that a treatment will lead to a cure.

A study published in February is the latest in a number of experiments with a "double blind" design, to sidestep the placebo effect. The Italian researchers tested 61 non-coeliac patients who believed they had gluten sensitivity, dividing them into groups that either received a daily dose of gluten or a rice starch placebo for a week, before swapping to the other treatment. Neither the patients nor the researchers knew until after the experiment who had been given the placebo first, and who the gluten first.

Many of the patients suffered symptoms including intestinal problems, foggy mind and depression while they were taking gluten, suggesting it really was the source of their problems.

The lack of physical biomarkers for gluten sensitivity also means that it is hard to know how many people are affected. Fasano's best guess, which he has arrived at by looking at patient records, is 6% - a much higher number than coeliac disease's 1%.

But with 29% of American adults trying to avoid gluten, that still leaves 22% - 53 million - who are not on the spectrum of gluten-related disorders, but who say they want to cut gluten from their diet. In 2013, 200 million gluten-free orders were made in restaurants, according to NPD.

"We've been scratching our heads to understand this social phenomenon," Fasano says. "We started this crusade, so to speak, to really make the North American community aware that coeliac disease existed. We didn't realise that this pendulum was going to go out of control and go all the way to the other side."

Percentage of Americans hoping to cut back on gluten (NPD Group)

When I ask if adopting a gluten-free diet can help someone lose weight, Fasano laughs. "If you go on a gluten-free diet, taking substitutes like gluten-free beer, pasta, cookies and so on, if anything you gain weight. If you take a regular cookie, it's 70 calories. The same cookie, gluten-free, can go as high as 210 calories.

"You have to substitute gluten with something that makes that cookie palatable, so you have to load it with fat and sugars. Just consider that. A gram of protein is four calories, a gram of fat is nine."

But, he adds, it may be possible to lose weight on a gluten-free diet by choosing natural products like fresh fish, meat, vegetables and fruit.

Two best-selling books, Wheat Belly by William Davis, and Grain Brain by David Perlmutter, have been particularly influential in steering healthy Americans away from the "dangers" of wheat and gluten. Both books make frequent reference to Fasano's research, but he says they are full of exaggeration and generalisation ("Gluten and carbs are destroying your brain," reads the back of Perlmutter's book). Frustrated by the sensationalist coverage, Fasano published his own book last year, Gluten Freedom, written with Susie Flaherty.

He says that eating gluten poses no risk to people who fall outside the spectrum of gluten-related disorders - and most experts agree with him.

"It's really important when we have something like gluten, to let the science be slow and humble," says another writer on the subject, Alan Levinovitz. "We always jump the gun on dietary science, and we've done it again and again and again."

A scholar of religion and literature, it may seem odd that Levinovitz has been drawn into the gluten debate. But he says he sees the anti-gluten fad as connecting powerful myths of a past paradise with a trendy anti-corporate attitude to the food industry.

The great gluten divide

41%

of US adults think gluten-free diet benefits everyone but...

44%

say they are a fad

-

$8.8bn: value of the gluten-free market in the US in 2014

-

$14.2bn: projected value by 2017

In his new book, The Gluten Lie, Levinovitz points out that it is not the first time that a treatment for coeliac disease has become hip. American doctors in the 1920s, ignorant of the role of gluten, put coeliacs on a diet of bananas and milk, supplemented with broth, gelatine and a little meat. They thought the bananas contained special enzymes that helped the patients - in fact, the diet worked merely because it excluded any gluten-containing foodstuffs. However, by the 1930s, the "bananas and skimmed milk" diet had become a weight-loss craze in the US.

The tennis star Novak Djokovic believes he owes his stellar 2011 season to giving up gluten. In his book Serve to Win, he describes the moment his nutritionist Igor Cetojevic gave him a slice of bread and told him to hold it against his stomach while he held his other arm out straight. Then Cetojevic pushed down on his arm. "With the bread against my stomach, my arm struggled to resist Cetojevic's downward pressure. I was noticeably weaker," the tennis star writes. "This is a sign that your body is rejecting the wheat in the bread," Cetojevic told him. (Djokovic did go on to have a blood test too.)

Many of the celebrities who have given up gluten - a list that includes Gwyneth Paltrow, Miley Cyrus and Victoria Beckham - say they have not removed gluten from their diets for fun, but because they have an intolerance, one usually identified with the help of a nutritionist or health guru.

"The loudest evangelists are the ones for whom it genuinely works," says Levinovitz. "So maybe there is someone who was undiagnosed with coeliac, or maybe it's someone who really did have non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. There are people who actually do treat genuine physiological conditions with dietary changes that they have chosen to undertake themselves, having gone to unsympathetic doctors.

"But those stories have snowballed into a much larger community of people, who think, 'Well hey, if it works for my friend who really seems to love it, I should try it.' Then of course, the placebo effect, combined with the fact that they are not drinking five beers a night, makes them feel better and they think it was that gluten."

In his book, Levinovitz also discusses the "nocebo" effect - the idea that a belief that something can do you harm really brings about negative effects. Could it be that a great swathe of America is really undergoing what doctors refer to as "mass sociogenic illness" when it comes to gluten?

Unsurprisingly, people don't like to be told that their illness is all in their head. Levinovitz knew he was going to get a strong reaction to his book, but he was taken aback by the scale of the hate mail he received.

"If you tell someone, 'Hey, scientists have just found out that Pluto's not a planet' no-one cares. They just say, 'Oh wow - it's a meteor? That's great.'" But, he says, telling people about food myths is like attacking their identity.

"It's terrifying to think that we might not understand ourselves. That we might be mistaken about our own bodies and about the effects of what we put into our bodies on ourselves. In retrospect, I wish my tone had been a little less mocking, a little more sensitive."

Gluten-haters Gwyneth Paltrow, Victoria Beckham, Novak Djokovic and Miley Cyrus

But Levinovitz strongly believes that the gluten-free fad is not risk-free. Many patients with eating disorders, he says, began their downward journey with exclusion diets. For the vast majority, this is not an issue, but cutting out gluten remains difficult, and potentially expensive and harmful to our relationship with food. In fact, there is some evidence to suggest that extreme anxiety about what we eat can lead to symptoms that are not unlike those of gluten sensitivity.

For coeliacs like Jodie Brain, another acquaintance I made at the Allergy and Free From exhibition, the gluten-free fad has been helpful in some ways. "It's useful in that it makes supermarkets bring in more products because more people are buying them," she told me. Years ago, gluten-free bread came in a tin. Then, in the 1990s there was a joke that you had to eat gluten-free products on the day you bought them because afterwards it would be impossible to tell them apart from their cardboard packaging.

As he grows up, my little boy will benefit from an unprecedented range and quality of food products for his condition. It is also brilliant that when you tell people in cafes and restaurants that he is gluten-free, they actually know what you are talking about.

But although I rarely get blank stares, I do sometimes catch sardonic looks exchanged between staff. When my wife explained his condition to one chef, he replied: "Oh so he actually can't eat gluten then. Most people, when I show them the allergy menu, change their minds and ask for something off the normal one."

Jodie Brain agrees. "People see you as: 'Oh - faddy diet'," she says. "We have to do it, we don't have a choice, whereas those people do."

About three weeks into his new diet, Sam is ready for his second birthday party (gluten-free)

The author and his son

Gluten-free diets were discussed on Health Check, on the BBC World Service.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.