The direct mail that tugs the heartstrings

- Published

The death of Olive Cooke focused attention on the way charities raise funds - and in particular on the pleas for donations that arrive via direct mail. What exactly are the techniques used by charities?

The letters on the doormat promise that you - you personally - can help. That your £5 a month will irrigate a village or help cure cancer or house a neglected dog.

Mailshots are still going strong despite the advancing digital age. In 2013 UK charities spent £239m or 61% of their advertising budgets on direct mail, according to one study, external.

Now it's facing a backlash. The death of 92-year-old poppy seller Olive Cooke - whose inquest is due to open - provoked widespread press condemnation of charities that reportedly sent her 180 letters a month. Mrs Cooke's family, however, said that although the requests were "intrusive" they were not to blame.

Whatever their role in Mrs Cooke's death, the case has sparked a debate between supporters of charity mailings, who say they are essential for good causes to generate income, and critics who accuse them of relying all too frequently on guilt trips and shock tactics.

For instance, in 2013 the Advertising Standards Agency censured, external a campaign by a cancer charity featuring a plain brown envelope with the words "It Doesn't Matter To Me Who YOU ARE" on the front in lieu of an address. A letter inside stated: "I AM CANCER ... I don't care who I hurt." One charity was criticised, external when it sent out a mailing aimed at new mothers showing an apparent ultrasound scan of a foetus, accompanied by a letter stating "Polly" had died at birth and asking for donations. The campaign was withdrawn.

Following the death of Mrs Cooke, Conservative MP Andrew Percy said there should be legal restrictions on "nuisance" charity letters, while Civil Society Minister Rob Wilson called for "thorough and quick action" from charities and regulators. The Daily Mail has conducted undercover investigations into companies that cold call people on behalf of charities.

Olive Cooke's death has sparked a debate over the tactics of charity marketing

Charities say the extent of the problem is exaggerated and that most behave responsibly. There were 201,400,512 addressed and 242,940,851 unaddressed direct mail "asks" sent by 1,203 UK charities in 2013, according to the Fundraising Standards Board, external. These generated 16,966 and 1,260 complaints respectively.

This sheer volume of mail is evidence of how seriously the non-profit sector takes direct mail, and it makes considerable effort to target its efforts.

For instance, research indicates that women aged 45-64 are the group most likely to donate to charity (67% in 2010-11). As a result, it is this demographic group that finds itself the target of direct mail.

"It's still the case that many of them remain attached to receiving and sending mail. They are a generation that grew up receiving and sending letters," says Stephen Lee, professor of Voluntary Sector Management at Cass Business School.

As a result, he says, it's common practice for charity letters to be addressed in type that resembles a personal hand-written letter, and for the envelope to be stamped rather than franked.

As well as obtaining addresses from known supporters, they also share details of people who have agreed to be contacted by third parties with other charities, says the FRSB. They also purchase contacts from list brokers and lifestyle survey agencies, who themselves receive address details from people who voluntarily give them out or fail to tick boxes saying they do not wish them to be passed on.

Charities can buy mailing lists from £140 for 1,000 names, or more should they wish to target people on the basis of certain factors of geography, gender or age. There have been complaints that this can result in individuals finding themselves bombarded with mail.

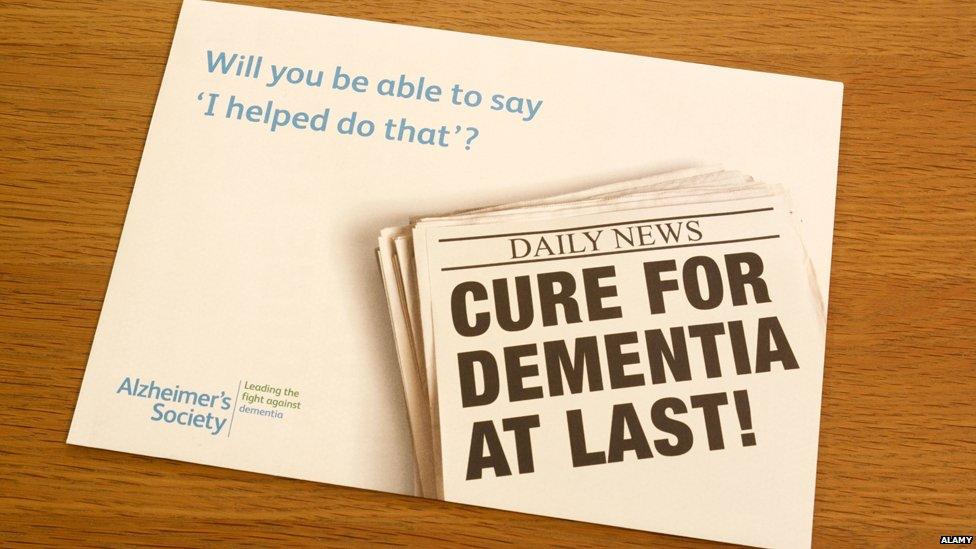

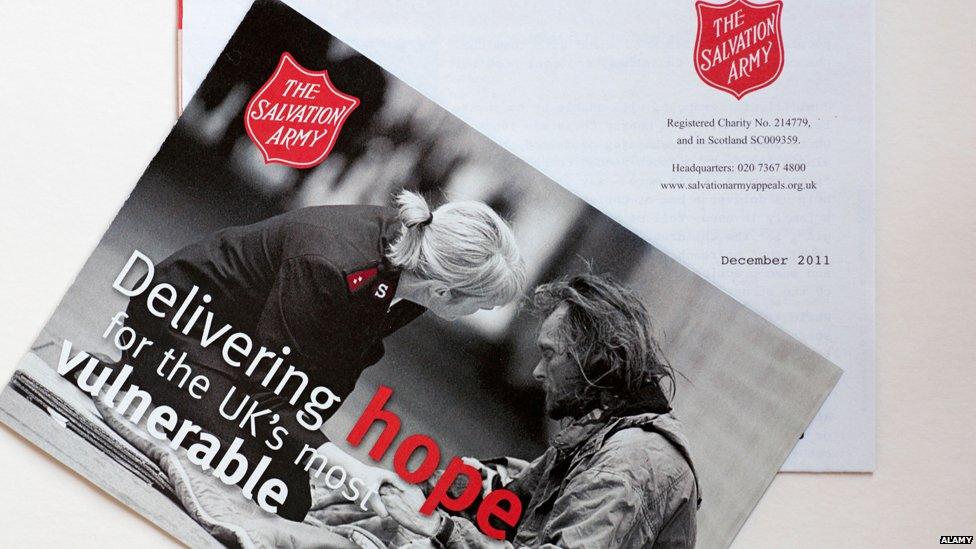

Direct mail is carefully targeted to generate a "human response", according to fundraisers

Direct mail can mean quite different things. It can consist of leaflets hand-delivered by volunteers or, most commonly, letters sent through the postal system. The FRSB recommends that people who do not wish to receive unsolicited post register with the Mail Preference Service.

It can be "warm", sent to people who are already known to be supporters of the cause, or "cold", directed at people who have never before engaged with it. A 2013 study suggested that the former had a return of £2.98 for every £1 spent by the charity while in the latter's case the return was 44p for every £1.

Whoever is the target, the first objective of the mailing is to get the reader's attention. The best way to do that, most fundraisers judge, is to try and make some kind of emotional connection.

"It's a fundamentally human thing that people will give to people," says Danielle Atkinson, assistant director of public fundraising at Breast Cancer Now. "People are supporting breast cancer research because of their mum, their daughter. Giving the story of an individual is what will create a human response."

As such the envelope might typically show a picture of a woman who has survived breast cancer, her name and an invitation to read her story, Atkinson says. It would also include the charity's logo.

Inside would be a letter, with the key information at the top and the bottom - there's evidence to suggest those are the parts people read, Atkinson says. The reader will be told exactly what a £5 or a £10 donation will provide. One crucial point may be repeated in a PS. There needs to be a pay form and a pre-paid return envelope. "It's about making it easy for people," says Atkinson.

Other mailings are more direct. A common criticism of some fundraisers is that they resort to upsetting or guilt-inducing imagery in an attempt to provoke donations. There are also questions about the use of child models to portray emotive case studies without prominent disclaimers.

In 2012, there were protests, external about a "disturbing and offensive" mailing by the NSPCC which included a DVD case emblazoned with the words "Kerry's father asked her to do the unthinkable. And then he filmed it." The ASA did not uphold the complaints.

The Institute of Fundraising's code of practice says organisations must not send communications "intended to cause distress or anxiety".

Lee says that while human stories are all well and good, guilt-tripping and shock tactics are counter-productive. "It not only creates bad feelings, it's not very good from an efficiency and effectiveness point of view," he says.

While such a strategy may grab people's attention in the short term, it makes far more sense, he says, to develop a positive relationship with donors over time - it being 10 or 11 times more expensive to find a new supporter than to solicit funds from an existing one.

But there's a line to be drawn. Almost by definition, good causes tend to provoke strong emotions. "If I am going to ask you to give to a duty or cause I have got to tell you why that's important," says Tobin Aldrich, a non-profit sector consultant and former fundraising and communications director for charities WWF-UK and Centrepoint. "If people in developing countries are dying because they don't have enough food I should tell you that."

Some charities take a different approach and include gifts like pens, stickers, bookmarks, coasters or Christmas cards adorned with robins, external in their mailings. It's a tactic that makes some people uneasy, including Aldrich.

"What you are asking is voluntary donations for which you get nothing in return," he says. "Pens and stickers and things like that can get in the way. Most mainstream charities use them pretty sparingly." The IoF code of practice states that they must not be used to "generate a donation primarily because of financial guilt or to cause embarrassment".

Sending cash through the post, usually accompanied by a message suggesting what could be done for a good cause with this 10p or 20p coin, has long been banned by the IoF code of practice. But in 2009 it was condemned by a minister as an "annoying practice", external with which some charities persisted.

The other issue fundraisers must contend with is the frequency of mailings. Do it too often and you annoy your supporters - too little and you pass up the opportunity of securing much-needed cash.

Atkinson says Breast Cancer Now supporters who give regularly by direct debit receive two newsletters, a thank-you message and one appeal every 12 months. Those who have donated on an ad-hoc basis receive the same but with four appeals each year. These are timed to coincide with Christmas and Easter when donations tend to rise. If fewer or no more mailings are requested, this is respected - it's not in the charity's interests to antagonise the people who fund it, she says.

Not all charities do respect these kinds of requests, however, as Lee acknowledges. In the long term they damage their own cause, he says, and the fault lies with the demands put on fundraisers. "It's the pressure they receive from their own organisation. More and more short-term-ism, treating donors like consumers."

For all that people complain about these mailings, many clearly consider them the least-worst option. A 2012 study suggested, external 59% of UK adults did not like being contacted by charities with which they did not have a direct relationship, but direct mail was the best-preferred method of communication.

Aldrich says it remains a necessary tool for fundraisers, too - good causes would simply not be so well resourced without it, says Aldrich. "At the end of the day if you don't ask for anything you don't get anything."

More from the Magazine

Every year, thousands of us across the UK donate our used clothing to charity - many in the belief that it will be given to those in need or sold in High Street charity shops to raise funds. But a new book has revealed that most of what we hand over actually ends up getting shipped abroad, writes Lucy Rodgers.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.