When the US president travels, the world stands still

- Published

Not quite a simple walk in the park when Dad is the president of the United States

US President Barack Obama pines for the moment when he can leave the security bubble. After 24 hours inside it, I can see why.

Mr Obama and his daughter Sasha, 14, walk across a tarmac in New York on Friday. He taps her shoulder and points towards Manhattan, showing her the world, or at least his version of it.

What a place.

They fly on Air Force One to one of New York's airports - and minutes later arrive by helicopter in Manhattan.

Streets are blocked off, and their motorcade glides to the Upper East Side. They run red lights - at least 26 over the weekend. Along the way people cheer. At one point a woman in a flowery sundress holds up a handmade sign: "FREE HUGS".

It's a New York fantasy, one of the perks of Mr Obama's job. He travels in a security zone, a "bubble" as it's known - a tightly managed network of aircrafts, vehicles and communication that lets him move easily around the world.

At a briefing Mr Obama says he likes to travel when he's free to go where he wants

The bubble provides safety, but it's confining. In a recent briefing he sounded wistful about an upcoming trip to Kenya, his father's homeland. He made it clear he'd rather go without security restrictions.

"I'll be honest with you, visiting Kenya as a private citizen is probably more meaningful to me than visiting as president," Mr Obama said. "Because I can actually get outside of a hotel room or a conference centre."

He still has 18 months left in the bubble, though. For that reason it's worth looking at the experience - and considering what it means in terms of his worldview.

The presidential bubble is thick - and pricey. Mr Obama rides in the motorcade in a limousine known as the Beast, which is designed to withstand bullets and chemical attacks.

Mr Obama flies on a Boeing 747 jet that costs $180,000 (£116,000) per hour to operate - and can be refuelled in the middle of a flight. Electronic equipment on board is designed to withstand all kinds of duress, including force from an electromagnetic pulse, according to White House officials.

On the aircraft Mr Obama has a suite with its own bathroom, as well as an office and a conference room. He has access to classified material, and he can communicate with military officials if the US is under attack or is facing another kind of emergency.

Mr Obama shows his daughter around New York - under tight security

There is a saying in the UK that everything smells like fresh paint to the Queen because wherever she goes, things are done up. Here in the US presidents are treated like royalty.

When you climb onto Air Force One, it smells like leather. The seats are business-class sized, even in the back.

I'm a new "supplementary" member of the "travel pool", a group of journalists who accompany Mr Obama on trips so they can report on what's euphemistically known as a "transformative moment" - for example, if the president gets shot. It also gives reporters a chance to experience in a visceral way presidential life on the road.

As we get settled, a flight attendant brings out cool white towels and a basket with grapes, bananas and oranges.

Almond Joy and Baby Ruth candy bars are displayed on a table near a row of magazines in white binders. I put a box of M&M's with a presidential seal in my bag.

Two cameramen watch golf on television. "Atlantic City," says one, looking out of the window. "It's much cleaner from up here."

Everything in the bubble, including the Jersey shore, looks scrubbed.

Even my colleagues and I are "clean", since we've been "wanded" (swept by hand-held metal detectors) and inspected by bomb-sniffing German shepherds.

Once you're in the bubble, you can't chat with those who aren't "clean".

This keeps the president safe. It also cuts you off from the world - and shows the cloistered nature of the one he inhabits.

Mr Obama has to stoop slightly when he gets on board the helicopter in New York so he doesn't bump his head.

Afterwards my colleagues and I head across the tarmac to an Osprey aircraft, propellers spinning.

The gusts of air are hot and fierce, and I almost lose my footing. The aircraft shakes in the air, and you can feel it vibrate in your throat. I see a red buoy in churning water, like a fragment from a Turner painting, and we fly over South Street Seaport.

FDR Drive on the east side of Manhattan is closed down for our motorcade. Traffic is blocked for miles.

"Wave like the queen," a friend in Boston had advised me.

Police line the streets on the Upper East Side, where Mr Obama attends a Democratic fundraiser. Nearby a mailbox has a padlock and a red sign: "This collection box has been locked." This makes it harder to stuff it with explosives.

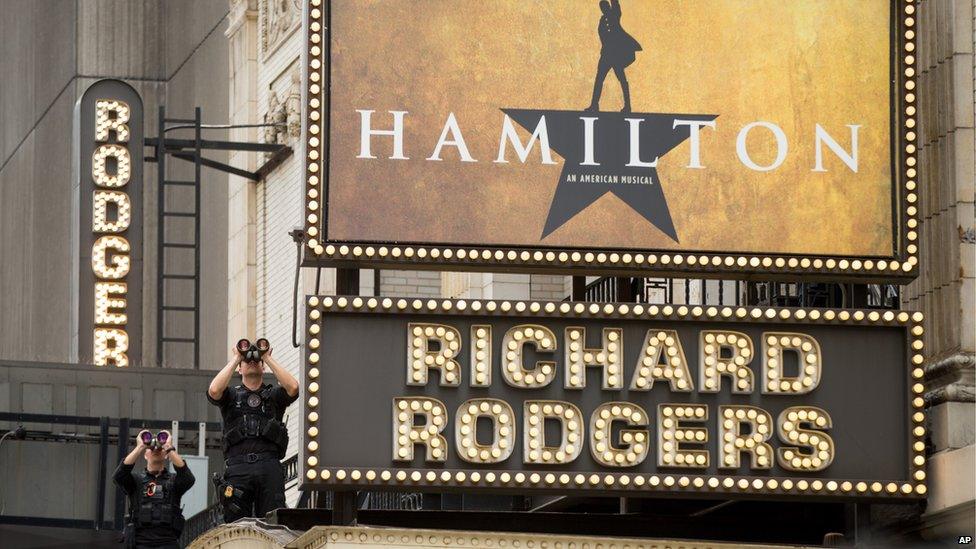

In New York Mr Obama is protected by police officers - and dump trucks

In other places, dump trucks block the streets. Gravel is piled in the back of one truck marked "sanitation".

The following morning the president is chewing gum on a walk near Central Park's Sheep Meadow. "We love you, Obama," someone calls out.

Secret Service officers wade through the grass, checking for bombs and assassins.

Afterwards Mr Obama goes to a Broadway play.

A worker from a nearby French restaurant says they closed for a couple hours because of the security. "Not a big deal," he says, adding they haven't lost much business. "One or two tables."

A lanky man named Michael, who's carrying an iced coffee, walks up. A police officer stops him. "I'm trying to get to a place upstairs," Michael says.

"An AA meeting," he tells me, referring to Alcoholics Anonymous, afterwards. "I happen to be in the wrong place at the right time," he says. Like others in New York, he takes it in his stride.

For the president, though, the bubble is more than an inconvenience.

After six years in the bubble, he's been accused of showing impatience with those who disagree with him, especially when they work on Capitol Hill.

When making a case for the Iran deal, he says, dismissively, to members of Congress - "read the agreement".

The bubble makes things worse. You're surrounded by people who are pre-screened and see the world the way you do.

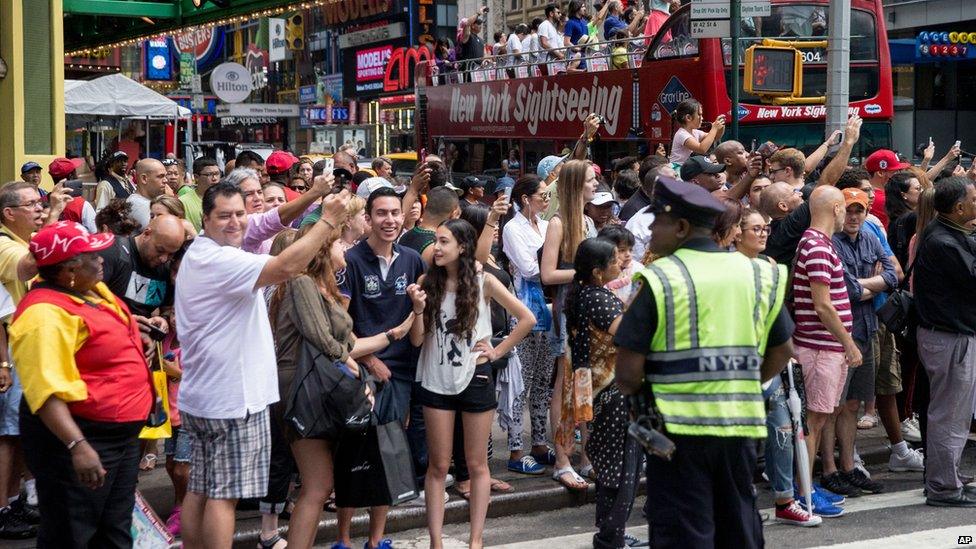

After the show he rides through Times Square. Hundreds of people are cheering, but the motorcade windows are rolled up. The world is muffled and distant.

You can see the crowds, but you can't hear them. You simply float by.

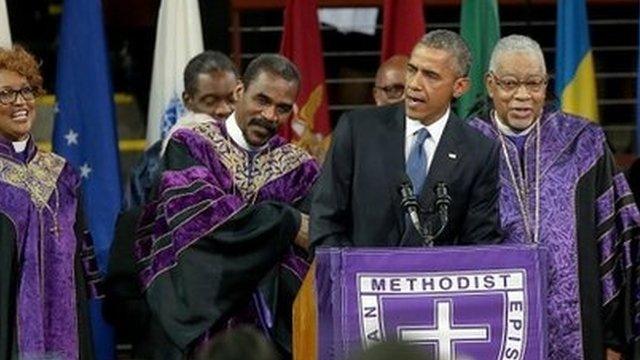

- Published14 July 2015

- Published26 June 2015

- Published10 November 2014