Why can't men be Olympic synchronised swimmers?

- Published

At the World Aquatics Championships, which begin this weekend in Russia, men will be competing in synchronised swimming for the first time. Men were a part of the sport at its inception, but until now they have always been barred from competing at the highest level. Will the door to the Olympics open next?

There is nothing in the world that can prevent 25 July 2015 from being the best day in Bill May's life. "It's something that I have dreamed of my entire life," he says, "to step out on that deck with the world's best."

Many already count May as one of the world's great synchronised swimmers. Next weekend, 11 years after he retired, he will get his chance to prove it. Whether or not he ends up winning his event, the chance to compete in the US team at the World Championships in the Russian city of Kazan is the delayed culmination of a career that has brought triumph and frustration in equal measure.

May made his big splash in 1998, when he and his partner Kristina Lum won the duet event at the US National Championships, then took silver at the Goodwill Games. He was named USA Synchro's athlete of the year in 1998 and 1999, and he went on to win 14 national events as well as titles in France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland.

But he was prevented from performing at the World Championships or the Olympics because it was seen at the highest level as a sport for women. May's coach Chris Carver said: "Let me tell you this - he not only would have made the team, he would have been among the very top of the competitors on the US team."

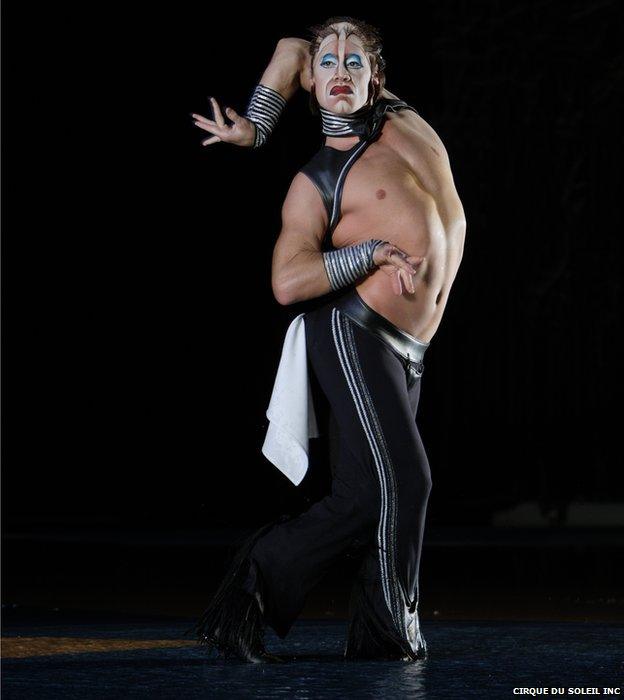

Bill May in Cirque du Soleil's O

May retired and started a stint that still continues, as the male lead in O, a water-themed Cirque du Soleil production in Las Vegas.

Then suddenly last November there was an announcement from Fina, world swimming's governing body, that mixed technical and freestyle duets would be on the programme of the World Championships. Bill May came out of retirement, and he brought two former teammates with him.

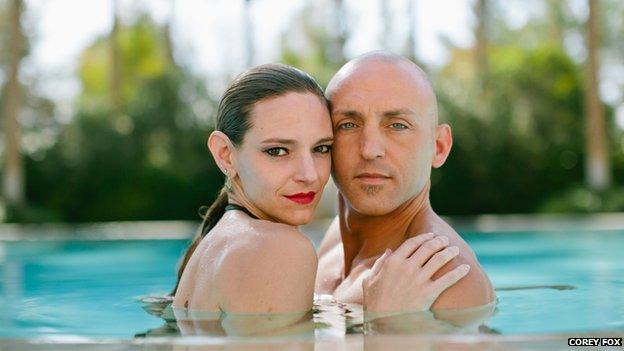

His partner for the technical routine is former Olympian Christina Jones, 27, who also appears in O, and for the free routine he will be reunited with the woman with whom he first won the US National Championship 17 years ago - Kristina Lum Underwood.

By synchro standards, this pair is positively antique. While the next oldest member of the US team is 25, May is 36. Lum Underwood, meanwhile, is 38 - and had a baby in January.

"I sort of felt guilty at the thought of leaving my children, leaving my husband," she says. "It was just one of those things, that I knew I would regret if I didn't at least try to do it. This seems like the perfect way to finish that part of our story."

She appears in a different Las Vegas show, Le Reve - The Dream. It is fate, May says, that all three of them were still involved in synchro, and were living in the same city, so that they could train together.

Christina Jones, Kristina Lum Underwood and Bill May mark 50 days before the World Championships

But they were not the only ageing athletes to receive the sudden call-up late last year. Benoit Beaufils, 37, will be representing France in the free routine with his partner Virginie Dedieu, even though he retired from competition in 1998. He and May have known each other for 20 years, and their lives have followed a remarkably similar trajectory.

Beaufils grew up in the small town of Montauban, near Toulouse. Like May, he got into synchronised swimming because a sister was attending classes. Already a keen gymnast, the six-year-old Beaufils found it impossible to sit on the deck and watch the other children splashing about having fun.

"Whenever I had the chance I just jumped in the water," he remembers. "I was just trying to copy what the girls were doing. Without really being coached, I just caught on to the sport."

One day, a recruiter came to watch the class, which was coached by his mother. "My mum said, 'Don't go in the water tonight. There is a very important lady coming.'" French sport should be thankful that the mischievous Beaufils ignored this instruction, and was singled out by the spotter as having an unusual natural talent.

The club began to create special roles for him. His routines included playing Charlie Chaplin and performing a Rocky solo to Eye of the Tiger. "There was always something I could bring to the part that the girls couldn't and I think my coaches were keen on that. They didn't want me to swim to Swan Lake, you know?"

He was teased, of course, but he says the snide remarks - being called "a queer" by classmates - just bounced off him. "I had a very hard shell on me," he says.

Eventually, Beaufils relocated to Paris, and in 1995 he became the French junior champion - competing mostly against young women - and was talent-spotted once again, this time by Chris Carver, who enticed him to go to California to train with the elite Santa Clara Aquamaids the following year. Bill May was already in the team, having moved from the East Coast when he was 16.

They trained eight hours a day, six days a week. "My mum, she used to work two jobs when I moved to California, just so that I could swim and pay my rent," May recalls.

Synchro had been an Olympic sport since 1984, but only as an event for women. Nevertheless, the men kept training in the hope that a chance might come for them to compete at the top international level, at the Olympics or World Championships.

"It was frustrating, but I kept wanting to compete," says Beaufils. "Knowing that there was Bill also at the time - I would be France, he would be the US - we kept thinking, the better we get, the better the chances that they will change the rule. Unfortunately, they never did."

Find out more

Bill May, Kristina Lum Underwood and Ginny Jasontek spoke to Sportshour on the BBC World Service in May

In 1998, Beaufils's parents said they could no longer fund his training, and he quit synchro to take the role in O that is now played by May. He later went on to become an acrobat in Le Reve - The Dream, appearing alongside Lum Underwood.

The phone call he received last September, asking if he would be willing to represent his country, was the highlight of his career. "Even though it was 17 years after I would have liked it to be, I couldn't say no to the opportunity," he says.

He and May got on the phone straight away. "We were joking around, saying, 'Can you believe this? This is actually happening.' We know that at the World Championships there will be the old school, which is us and the Americans, and then all the other ones who are 18. We will be literally twice their age!"

Because of his circus work, Beaufils was still in great shape, but he had developed the body of an acrobat, not a swimmer. His muscles had contracted so much that he struggled to get the length needed to drive through the water. For three months, his coach made him swim lengths.

Then from January, she started to send Beaufils videos of moves that she and Virginie Dedieu were practising in France, and on the other side of the world he tried to replicate them - synchronised swimming with a nine-hour time difference.

Virginie Dedieu and Benoit Beaufils

Meanwhile Bill May was starting to train with his two partners. Once or twice, Beaufils found himself in the same pool as May and Lum Underwood, but with an effort of will he forced himself to turn his back on their routine, knowing that they wanted it kept secret. "I would see some parts for a second, and be like, 'Oh that looks great!' and turn back."

Every night he and Lum Underwood saw each other backstage, looking ravaged from their training regime, not to mention the lack of sleep that comes with having a young baby - Beaufils had also recently had a child. They would sympathise and ask non-specific questions about how training was progressing. Beaufils could only train for two or three hours a day - any more and he was too exhausted to perform on stage.

Despite its glitzy sheen, synchronised swimming is one of the most demanding sports. Performers need to hold their breath for long periods while carrying out a dizzying array of kicks and turns upside-down in the water. Hardest of all, when they re-emerge they must resist the urge to gasp but force their face into a winning smile.

In February, Beaufils and Dedieu finally met. "The first time we ever got to swim together was very intimidating because she's such a huge person," he says. At 5ft 5in (164cm), Dedieu is not physically huge, but within the sport the 36-year-old has an indomitable stature - the only person ever to have won the World Championships three years in a row. "She's also very humble," Beaufils says. "She's absolutely divine."

On the first day, the duo spent a few hours improvising, getting to know one another's capabilities, personalities and bodies. At the end of the day, their coach removed her sunglasses and had tears in her eyes. "She said: 'You guys. You are so natural together, so beautiful together.' We really do have a great connection in the water - I think that could be what sets us apart a little bit at the World Championships."

Virginie Dedieu is France's most successful synchronised swimmer

Although he doesn't want to go into specifics, their routine will be much more like a ballet pas de deux than a conventional female synchro duet, in which the competitors typically swim next to each other, creating a series of perfectly mirrored figures. "We wanted to really use the fact that there is a man and woman in the water," he says. There will plenty of synchronisation, but in-between a lot of lifts and interaction between the swimmers.

Bill May and Lum Underwood are also likely to bring something dramatic - US team coach Myriam Glez has described their routine as "intense and powerful". The pair have cited as a key influence Torvill and Dean, the British duo famous for imbuing figure skating with a strong sense of narrative, even romance. (Britain will not be represented in the synchro competition.)

Since this is the first such competition at this level, no-one really knows what the judges will be looking for. From videos that have circulated online, it's thought that in the free routine the Ukrainian swimmers will be tightly synchronised - a difficult thing to achieve in a mixed duet - while the Japanese pair will be much freer.

"We kind of understand that a mixed duet should be different from a female one, but there are no special criteria," says 20-year-old Alexander Maltsev, the Russian competitor.

"Most likely, they will judge us on the female rules.

"Men's choreography is different from women's. It's a completely different style. In a mixed duet the man should personify strength, power. The woman, on the contrary, beauty and grace."

Darina Valitova and Aleksander Maltsev during the mixed duet test event in June

But stereotypes are also there to be challenged. At a test event in Rome last month, in which Maltsev and his partner Darina Valitova took gold for a technical routine, jaws dropped at the pair's first figure, in which the 18-year-old Valitova powerfully lifted Maltsev clear of the water.

Maltsev, who pursued a career in synchro despite attempts to divert his attention to water polo and diving, is regarded as one of the best young guns in male synchro.

But having won every Olympic gold in the sport this century, Russia did not react well to Fina's rule-change last year.

Sports minister Vitaly Mutko said synchro should be ''a purely feminine sport'' and hinted that the change had been pushed through by the country's rivals. Then Russia's synchro stars spoke out. "My attitude to male synchronised swimming is very negative," said four-time Olympic champion Anastasia Ermakova. "I am categorically against men in our type of sport," said three-time champion, Svetlana Romashina. ''I'd probably have decided against it,'' chimed in Angelika Timanina, Olympic champion, captain of the Olympic team and winner of eight World Championships. ''We're used to classical synchronised swimming, feminine synchronised swimming.''

Darina Valitova and Aleksander Maltsev

Maltsev says he can understand his teammates. "A lot of people just can't imagine it. But when they see it, they'll change their mind. I've always had a lot of opponents. I have taken part in meets non-competitively, because we didn't have an official category, but the audience reception was always warm."

Synchronised swimming had various precursors in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries.

One was ornamental or scientific swimming, the performance of which was a requirement of the Royal Lifesaving Society. The first formal competition took place in 1892, in Yorkshire, in the UK, when 14-year-old Bob Derbyshire won by performing front and back somersaults, a torpedo, and other stunts.

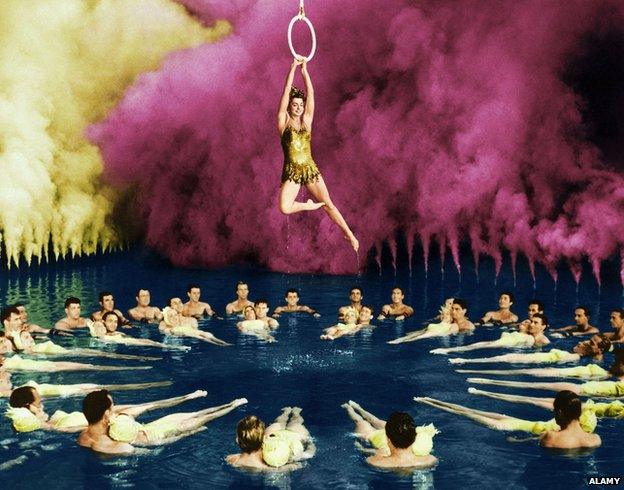

Male swimmers also played a role in the water pageants that became popular in the 1930s and 1940s. The most ambitious of these was the Billy Rose Aquacade, held in 1940 as part of San Francisco's Golden Gate International Exposition. The show partnered 50 "aquabelles" with 24 "aquabeaux" in three performances a day for a year, each playing to an audience of 7,000.

Billy Rose recruited two outstandingly beautiful champion swimmers for his show - the speed swimmer and future movie star, "bathing beauty" Esther Williams, and Olympic medal winner and A-list Hollywood actor Johnny Weissmuller, best known for playing Tarzan.

Kay Curtis (standing centre) with her mixed team The Chicago Tritons in 1940

Synchronised swimming as a sport developed alongside these pageants. When Kay Curtis, the woman who first set movements in the water to music, helped write a rulebook for the sport in 1940, the first rule stated: "Competitors may be men or women or both."

But when, the following year, synchro was adopted as a sport in the US by the Amateur Athletic Union, it took the decision to separate men and women. This brought it in line with all the other sports the AAU oversaw, in which men were not pitted against women.

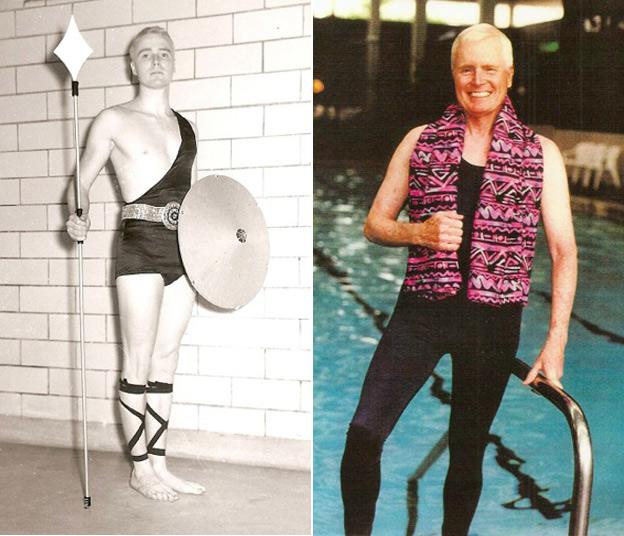

"It was designed for both sexes, and the AAU wanted it separate," says Bert Hubbard, who competed in synchronised swimming in the early 1950s. "But this whole idea that the male has so much more advantage in the water - if you're in the water you find out very quickly that being a man is more of a liability."

Hubbard in 1954 and 1996

Although men are stronger, they are less flexible so it is harder to get the necessary extension in the legs. Buoyancy is also an issue. "This sport is so difficult for men in general, because we don't actually float like women," says Beaufils.

In mixed duets, physical differences between men and women do not help any one team over another. But the AAU rejected the idea of these too, a "bizarre" decision Hubbard interprets as a prudish judgement that it was not right for scantily clad men and women to cavort together in the water.

Men were allowed to compete against other men - Hubbard won the national junior title in 1954 - but there was a lack of interest and the competitions died out. By this time the fantastically popular "aqua-musicals" that Esther Williams went on to make for MGM after her days in Billy Rose's pageant were fixing the idea that it was a feminine activity - girls in sequined outfits making pretty patterns in the water.

Esther Williams, though not a synchro swimmer, is credited with giving the sport its glitzy reputation

She was MGM's biggest star in the early 1950s - this is from her 1952 aqua-musical Million Dollar Mermaid

In 1978 the sport was opened up to men in the US, allowing them to compete alongside and against women, but any aspiring male synchro stars were soon to suffer further discouragement. When, after a 30-year campaign, synchronised swimming featured on the programme of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, it was for women only.

"The Olympic committee was bound and determined to have sports for women, so it got classified as a women's sport," recalls Dawn Pawson Bean, who was synchro competition director for the 1984 Games.

During Bill May's ascendancy in the late 1990s, his country's governing body of the sport, USA Synchro, lobbied Fina to allow men into the pool for the 2002 World Championships, but - crushingly for May - it was not to be.

"Unfortunately for Bill, because he's a tremendous talent, the time then wasn't right and Fina was not so much interested in adding men to the sport," says Ginny Jasontek, honorary secretary of synchronised swimming at Fina.

"And I also just think that the history of the sport, being a women's sport, was somewhat unique, and the feeling might have been to keep that as a women's sport."

One sports insider says that the IOC warned Fina that the sport could be dropped from the Olympics if it was opened up to men.

Paris Aquatique have been taking synchro seriously since 1998

But times change. Women now compete in every category of sport at the Olympics - though there remain two that are closed off to men (the other is rhythmic gymnastics). Some have interpreted Fina's hurried change of heart last November as a sign that the IOC might also be ready to include mixed duets.

The IOC says that it will only consider adopting male synchronised swimming after a formal request from Fina - and no such request has ever been made. A decision on inclusion would have to take place at least three years before a Games, and it would follow a thorough assessment of the event, including a survey of its popularity around the world.

National swimming bodies have decided that it may be worth their while increasing male participation in the sport. Although men have been allowed to compete in the US since the 1970s, the UK's Amateur Swimming Association (ASA) only changed its rules after Fina's decision last year - and it went a step further, allowing mixed combination teams too.

This presents a big opportunity for Out to Swim, a London club, which added synchro to its roster of activities in 2008. Its members took part in their first proper competition this month. The London club is one of a handful around the world which competes at an amateur level with all-male and mixed teams.

Some of the teams - including Out to Swim and Paris Aquatique - are linked to gay swimming clubs, and some of them are not.

"We had a lot of newspapers that wrote articles about us, and every single time they associated it with homosexuality," says John Fay, from Paris Aquatique. "We said, 'This actually has nothing to do with our sexuality. All that's going to do is proliferate the idea that this is a sport reserved for gay men - and it's not at all.'"

To get the extreme flexibility required to compete in synchro it is essential to start early, and Fay says that the stigma of boys doing what is perceived to be a girls' activity is a barrier to them enjoying what is "actually a pretty cool sport".

An early Superman-themed routine from Paris Aquatique

A rebrand for synchro may be on the way. "The modern way to look at it is this is essentially dance, but in the water," says Jamie Hooper, ASA's equality programme manager. He points out that 15 years ago dance classes held little attraction to boys, but with the rise of street dance groups like Diversity, the Britain's Got Talent winners, that has begun to change.

For Benoit Beaufils, it's all about exposure. Earlier this year, he and Virginie Dedieu went on a short tour of French swimming clubs with their duet. "Literally a week later, I got all these phone calls from coaches from these clubs, telling me, 'We had four boys that signed up since you came.'

"All these years I think there were a lot of boys who were interested in doing it, but they didn't because they didn't think that anybody did it. And nobody wants to go into a sport that will stop at a national level.

"This is my sport and I've loved it all these years, but a mixed duet is so much more interesting to watch than a two-girl duet. I think it's really the future of the sport."

Despite Beaufils' optimism, it may take many more years for the IOC to open the door to male synchronised swimming - but if and when it does, one thing is certain.

"If synchronised swimming went to the Olympics, I would definitely be there to compete," says Bill May. "Even if I'm 85."

Bill May in the water

Additional reporting by Tom Sabbadini and Rafael Saakov. Bill May, Kristina Lum Underwood and Ginny Jasontek spoke to Sportshour on the BBC World Service in May.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.