Purple Emperor: The butterfly that feeds on rotting flesh

- Published

For a few weeks in July, groups of people can be found wandering English woods carrying strange produce - including rotting fish, Stinking Bishop cheese and dirty nappies. They're out to bait the Purple Emperor, one of Britain's most elusive butterflies, whose beauty disguises some filthy feeding habits.

You never forget your first time, says butterfly enthusiast Neil Hulme.

"My dad and I were walking through the woods, and we came across a woman in her 30s wearing stars-and-stripes trousers, bent over. Some men in tweed with cameras and long lenses were photographing her from behind."

He moved closer and realised they were taking pictures of a Purple Emperor butterfly that had landed on her bottom.

Hulme was transfixed by the creature - especially when it fluttered up and landed on his collar.

The "Purple Emperor paparazzi"

"The butterfly paparazzi moved in and surrounded me," he recalls. "In blind optimism I held out my hand as a falconer might, and it landed on my finger. It was such an amazing experience. I was hooked."

So began a decades-long love affair, which has seen him devote almost every second of every summer to the pursuit of this mysterious butterfly. Now is the key time of year - by the end of July, all of the Purple Emperors will be dead.

Hulme's purple passion runs so deep, he gave his daughter the middle name Iris after its Latin name, Apatura iris.

Purple Emperor fan Neil Hulme: "It's a violent thug with the filthiest table habits imaginable."

The Purple Emperor is rare among butterflies. It avoids flowers, preferring rotting animal corpses, faeces, mud puddles - and even human sweat.

It dwells high in the tree tops in the domain of birds. The males, who boast the deep purple iridescence, spend their brief lives "drunk on oak sap, brawling in mid-air battles and chasing down virgin females", says Hulme.

"It's a violent thug. It attacks anything that comes into its airspace - it even tries to chase big birds like buzzards. It has filthy table manners."

The strange behaviour of "His Majesty" - as the Emperor is affectionately known - inspires equally unusual behaviour in people.

At Knepp Castle estate in West Sussex, people carrying huge cameras and binoculars can be seen dotted across the landscape.

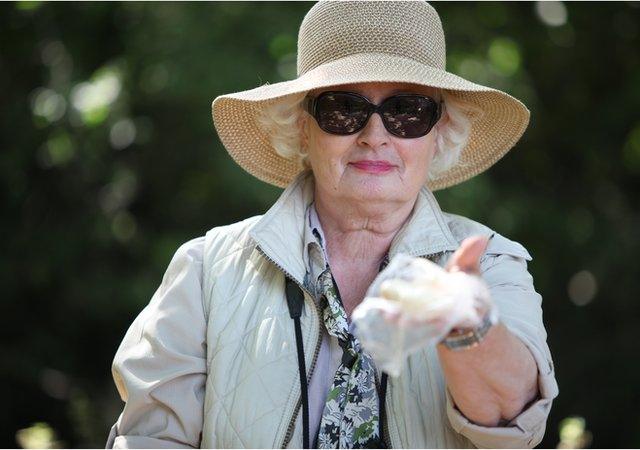

Trotting down one woodland path is 71-year-old Hazel Land, a dainty woman in a large straw hat and sunglasses. She's travelled some four hours from Devon in search of the Purple Emperor.

From her pocket she produces a lump of ripe Stinking Bishop cheese, lightly wrapped in cling film. "It really smells - want a whiff?" she offers. "It's my bait. I swear by it. And you can always have some for lunch."

Hazel Land and her butterfly bait - ripe cheese

She admits the Emperors seem to be off cheese that morning - but she passes on some intelligence about a female spotted on a bramble bush not far away.

Hulme, who now works for the charity Butterfly Conservation, has brought his own secret recipe - a foul-smelling Indonesian shrimp paste called Belachan, which he mixes with hot water and spreads on woodland paths. Sometimes he adds pickled mudfish.

People try "all sorts of ridiculous things" to bait Purple Emperors to the ground for a much coveted shot of its resplendent wings, he says. That includes roadkill, dog poo, rotting fish and even babies' nappies. It's thought the butterflies are attracted to the salts and minerals.

Rotting banana skins are traditionally draped around Bentley Wood in Hampshire

Specially-imported Indonesian fermented shrimp paste is one of Neil Hulme's secret bait ingredients

"My friend Matthew once hoisted a 15lb (7kg) salmon into the top of a tree," says Hulme.

"Urine-soaked fox scat [dung] is one of the most attractive baits there is to the Purple Emperor. I know of people who go out first thing and scoop them into a bucket.

"And there's a very good fish paste called Shito from Ghana - although I haven't managed to get hold of that for a couple of years now."

In Bentley Wood, Hampshire, people traditionally hang rotten banana skins - although Hulme is dubious about their effectiveness.

Rev John Woolmer's Purple-Emperor-themed stole

One clergyman, the Reverend Prebendary John Woolmer, who has a letter on the state of the Purple Emperor published annually in the Times, even calls on the power of prayer.

He conducts a woodland service at the beginning of each Purple Emperor season in Northamptonshire to bless the forest rides. His purple stole is embroidered with butterflies.

But while unusual, the tactics of these butterfly chasers are nothing new. The tradition of baiting Purple Emperors goes back at least 250 years.

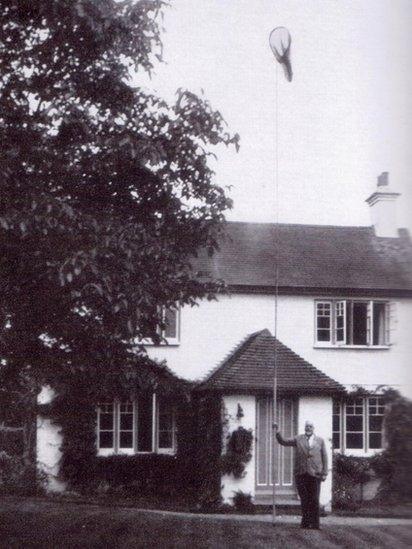

IRP Heslop and his 37ft butterfly net

In Victorian times, the heyday of butterfly collecting, gamekeepers would attract Purple Emperors down to their gibbets by hanging out rotting carcasses of crows and rabbits.

In the early 20th Century, expert lepidopterist and Purple Emperor obsessive IRP Heslop imported a trailer-load of pig manure for bait, and designed a 37ft (11m) net for scooping them from the tree tops.

More recently, people have tried cherry-picker cranes to access the canopy, or even floating purple helium balloons or hurling clods of mud into the air to provoke them into the open.

Hulme has ideas for sending up miniature kites or a drone - although the blades would have to be protected. "We wouldn't want to see one shredded."

Back in Knepp, another hunter, Paul Fosterjohn, is lying flat on his back - "the best Purple Emperor spotting position" - under a tall oak tree.

A 25-foot ladder is precariously secured with his belt to a mid-level branch that's oozing sap - a Purple Emperor delicacy. At the sight of one, Paul scampers up the ladder for a closer look and a photo, before diligently noting down every detail.

Paul Fosterjohn keeps a watchful eye on the treetops

He has spent much of the last two weeks in this manner. "I'm mostly interested in birds, particularly cuckoos, but there's something about the Purple Emperor. I don't know, it takes you back to being a child again."

Fosterjohn is still childlike in his captivation at every new sighting. At one point he spots a pair tumbling in a downwards spiral in the distance.

"It's a male-female rejection," he yells and begins leaping over brambles and ditches towards them.

Matthew Oates, who hoisted the salmon, author of In Pursuit of Butterflies, is the UK's leading Purple Emperor expert, and has dedicated 45 years to trying to understand them.

In previous years, he's held foul-smelling "butterfly banquets" on trestle tables in the woods, with plates of rotten shrimp and fermenting jellyfish slices to bait the insects.

Matthew Oates's "butterfly banquet"

He says only now are some of the mysteries surrounding this butterfly beginning to unravel. "A lot of knowledge about the Purple Emperor was assumption and mythology - there are huge areas about its ecology and other dimensions we don't know about," he says.

"For example, it was always thought they were dependent on ancient oak woodland. In fact the caterpillars feed on sallow - or pussy willow - thicket."

Sallow was traditionally seen by foresters as a weed, and rooted out.

Drunk on sap: A female Purple Emperor uses her long yellow proboscis to suck sap from an oak tree

The Purple Emperor spends weeks as a highly camouflaged pupa before emerging to spread its wings in July

But at Knepp, a "re-wilding" project by estate owner Charlie Burrell to allow parts of the land to return to its natural pre-agricultural state has allowed sallow habitat to develop over the last 15 years.

A boom in Purple Emperors has ensued, this year overtaking even famous hotspot Fermyn Woods in Northamptonshire for sightings. It could mark a huge step for conservation.

By August, the last of this year's Purple Emperors will die away. "You do feel sad when it's over for another year," says Hulme.

"Purple Emperors are this wonderful celebration of British summer. Matthew likes to say they just fly away into the sunset. It's nice to think about it like that."

'His Majesty'

The Purple Emperor was first defined as a species, Apatura iris, in 1758

It is one of the UK's largest butterflies, second only to the Swallowtail. It has a wing span of up to 8.4cm (3.3in)

The adult butterfly emerges in early July, with peaks in the second and third weeks of July. It is mostly found in woodland in central southern England

Its elusive nature makes it difficult to establish how many Purple Emperors there are in the UK, but it is considered a species of conservation concern

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published23 July 2015