Litvinenko: A deadly trail of polonium

- Published

Alexander Litvinenko in the intensive care unit

Newsnight's Richard Watson tells the inside story of a perplexing murder.

Wednesday, 1 November 2006 - a crisp, autumn day in London. The capital was heading for a beautiful weekend.

Security cameras captured Alexander Litvinenko on his way to meet two former colleagues from the murky world of Russian intelligence. The grainy black-and-white images show him walking out of frame as he entered the upmarket Millennium Hotel in Grosvenor Square in the heart of Mayfair.

He drank tea that day laced with a lethal dose of radioactive polonium.

Twenty-two days later, he was dead.

Who killed him and why? An intelligence source told the BBC he was murdered on the orders of the Russian state because he'd crossed two "red lines" by making direct allegations against President Vladimir Putin. The Kremlin has denied any involvement in the crime.

A public inquiry into the murder has been under way for five months. It's about to go into closed session to hear secret intelligence. A BBC team has had unparalleled access to key witnesses and has spoken to confidential sources close to the case.

Alexander Litvinenko was taken ill just hours after his meeting at the Millennium Hotel's Pine Bar with Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitry Kovtun, the two former Russian spies he counted as business contacts, even friends. He was admitted to his local hospital in north London on 3 November, vomiting and in great pain.

He told doctors he thought he had been poisoned. At first, local Metropolitan Police officers were involved. But soon word reached the then head of the Met's counter-terrorism command, Peter Clarke. "A colleague came into my office and explained that - in hospital in north London - was a man telling a quite an extraordinary story. He was saying that he was a former member of a Russian intelligence agency and that he believed he'd been poisoned by some of his former colleagues."

He was showing some signs of radiation poisoning. He was losing his hair. But when doctors passed a Geiger counter over his body the readings were negative. He was clearly severely ill, but no-one could work out why.

Two weeks after being admitted to hospital, Litvinenko was transferred by ambulance - with a police escort - to University College Hospital in central London for intensive, supportive care. His white cell blood count was catastrophically low. It looked as if his immune system was being destroyed.

He was showing signs of bone marrow failure. He was lined up for a transplant but he continued to get worse. His wife, Marina says: "When I came to see him it was exactly what you saw in the picture in the newspaper. After that he never came out from this bed. He was very, very weak already. He tried as hard as possible to give information to police."

Particle physicist Prof Ian Shipsey demonstrates how to test for polonium poisoning

The head of critical care at UCH, Dr John Goldstone, says the doctors had to deal with all kinds of unusual visitors. They were working closely with the police but there were other mysterious people too.

"The scene really was a mixture of individuals. A lot of people wearing suits. The police officers were there but there were some people who probably weren't police officers but were possibly members of the security services", Goldstone says.

The medics were told about some bizarre-sounding poisoning cases from the intelligence archives, allegedly involving the KGB. One story seemed to come straight from the pages of a spy thriller - an assassination target was killed by radiation after part of his desk was secretly replaced with a radioactive source. It was all very James Bond.

Prof Amit Nathwani, a blood consultant, was a key member of Alexander Litvinenko's medical team. "His vital organs were being destroyed in a sequential pattern. It started with his liver, and then was followed very rapidly by his kidneys and then his heart. We were in a race, trying to work out the cause before some of the other organs were picked-off."

After 18 days in hospital, his condition was still a mystery. "We knew that with organ failure and a failed bone marrow that we would struggle to save his life," Goldstone says.

Andrei Lugovoi, one of the men who met Litvinenko

As a last resort, it was decided to send small blood and urine samples to Britain's top-secret nuclear research site at Aldermaston in Berkshire.

Scientists at Aldermaston are more accustomed to working with nuclear weapons, but they used their expertise to search for radioactive poison. They first used a technique called gamma spectroscopy. This advanced analytical technique involves passing energy through the sample in a vacuum to search for radioactive elements emitting gamma rays. Each element has a unique signal at a particular energy level.

The results looked negative. However, they noticed a small spike in the read-out, barely above background levels, at an energy of 803 Kilo electron volts (KeV).

By pure chance another Aldermaston scientist, who'd worked on Britain's early atomic bomb programme decades ago, happened to overhear his colleagues discussing this small spike in the trace. He recognised it immediately as the small gamma ray signal from polonium-210. He knew this because polonium-210 was a vital component of early nuclear bombs.

Suddenly, everything made sense. It explained the failure to detect radiation poisoning in hospital. Polonium-210 emits vast amounts of energy as alpha radiation but it hardly emits any gamma radiation at all. This is why the hospital tests with Geiger counters were negative.

One of the world's most eminent particle physicists, Prof Ian Shipsey, who was part of the team that discovered the Higgs-boson particle, explains that polonium-210 is a very strong alpha particle emitter. It produces a lot of energy but in a confined space because alpha particles are easily blocked, for example by paper or skin. Hence it is harder to detect. "Polonium is deadly - 100%. If it's ingested in the body it destroys cells."

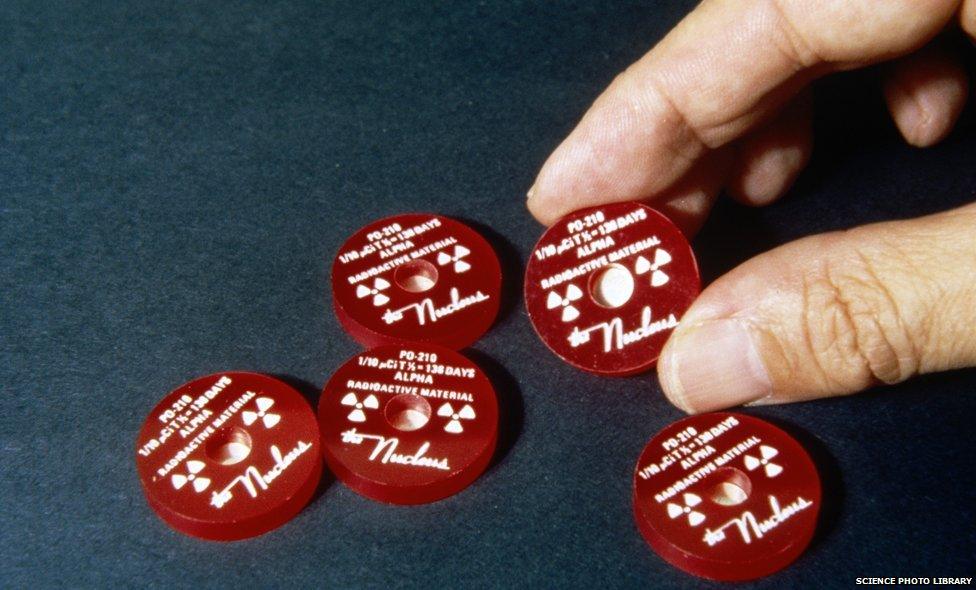

What is polonium-210?

Polonium discs

Naturally occurring radioactive material that emits highly hazardous alpha (positively charged) particles

First discovered by Marie Curie at the end of the 19th Century

There are very small amounts of polonium-210 in the soil and in the atmosphere, and everyone has a small amount of it in their body

At high doses, it damages tissues and organs

It cannot pass through the skin, and must be ingested or inhaled into the body to cause damage

Historically called radium F, is very hard for doctors to identify

Alexander Litvinenko had drunk contaminated tea at his meeting at the Millennium Hotel. He was being killed from the inside.

On that Wednesday night, 22 November, doctors at UCH were informed that the poison was probably polonium-210. Not that there was much they could do. Once Litvinenko had drunk the contaminated tea on 1 November, there was no going back. This was a death sentence.

The implications for public health were profound. This was in effect a radiological attack on the capital.

The government's Radiation Protection Division, based in Chilton, Oxfordshire, assembled a crisis team of 20 scientists. They worked through the night. How should they test for contamination? What about the doctors, nurses, his family, his house? And how about the hundreds of people he'd been in contact with over the past three weeks? A crisis was unfolding at alarming speed.

Back at Aldermaston, work was continuing to confirm the polonium-210 findings. Next, they tested a larger urine sample with a special kind of spectroscopy designed specifically to detect alpha radiation. By the morning of Thursday 23 November they had their result: Confirmed - polonium-210.

Alexander Litvinenko died the same day.

His wife Marina was allowed to say goodbye. "I was very pleased I was allowed to see Sasha for last time," she says with tears in her eyes.

Marina Litvinenko fought long and hard for a public inquiry into her husband's death

"This was a hideous attack on a British citizen and one that obviously he had no chance of surviving," says Nathwani. "I've been a consultant for over 20 years and I've never seen anything like this and I hope I never do again."

For the police, this had just turned into a murder investigation. At its height, the Met had more than 100 detectives on the case. If Litvinenko had died a week earlier, it would have been an "unexplained death". As it was, there was a trail of radioactivity to follow across the capital and beyond.

When the polonium was discovered, Marina Litvinenko was told it was not safe to stay at her home. "I lost everything. I had only 15-20 minutes to get some things with me, and be out of the house."

The government's civil contingencies committee, Cobra, met four times in the week after the attack. They were concerned about causing alarm by closing contaminated hotels.

A source told Newsnight that they even tested the London Underground - both trains and stations - and found traces of polonium. This remained secret at the time to avoid public panic.

"We were finding polonium in aircraft on which people involved in this inquiry had flown, in a football stadium, in restaurants, in hotels. And of course the public were very understandably very concerned," says Peter Clarke. More than 40 sites were contaminated.

The two men who'd met Alexander Litvinenko at the Millennium Hotel - Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitry Kovtun - became prime suspects.

The polonium trail started on 16 October 2006 when Litvinenko met Lugovoi and Kovtun in London. The sushi bar where they had lunch was contaminated. This is thought to be the day of a first murder attempt.

They spent the night at the Best Western Hotel in Shaftesbury Avenue. Heavy contamination was later found in both their rooms.

Lugovoi was back in London on 25 October. His room at the Sheraton, Park Lane, was contaminated.

Three days later he flew from Moscow to London. Polonium was found on his British Airways flight.

And Kovtun flew from Moscow to Hamburg on 1 November. Again polonium was found at locations he visited in the city.

This was the day when both Kovtun and Lugovoi met Litvinenko in the Pine Bar at the Millennium Hotel - the place with some of the most heavily contaminated locations of all.

Hotel security cameras captured Lugovoi, and then Kovtun, visiting the bathroom opposite the Business Centre before Litvinenko arrived. Lugovoi has his hand deeply buried in his pocket. Was he carrying the poison?

He says not, but sinks and a hand-dryer were later found to have been heavily contaminated with polonium-210, as was one toilet cubicle door.

When Lugovoi and Kovtun's movements were mapped against the sites of polonium contamination, there was an exact match. The evidence of guilt was strong. In May 2007, the then Director of Public Prosecutions Ken Macdonald announced that Andrei Lugovoi was to be charged with murder and his extradition would be sought from Russia. Kovtun was charged in 2010.

"This was not some random killing," says Lord Macdonald. "This was a killing with a very clear purpose and a killing with some state involvement."

So how strong is the evidence that the Russian state was involved?

The science around the choice of murder weapon - polonium-210 is strong. Prof Norman Dombey, a physicist who has a deep knowledge of Russian nuclear sites, gave evidence at the public inquiry.

Dombey says there is only one place where it can be produced in the quantities used in the murder - a military nuclear reactor at the Avangard plant in the closed city of Sarov. Sarov was where Russia produced its first nuclear bomb in the days of Joseph Stalin. This is a clear link to the Russian state.

But could organised criminals or rogue agents have got hold of polonium-210 in an unauthorised operation? Dombey says no. "Everything about polonium-210 is regulated by the state. Its transportation is regulated by the state and its use is regulated by the state."

But why would the Russian state want him dead? A look back through the Russian archives provides strong clues.

It is clear that Alexander Litvinenko had powerful enemies in Russia. Disturbing Russian TV footage from 1999 shows him in court facing charges of assault and stealing explosives. He said the charges were trumped-up.

Russian President Vladimir Putin

At the time, he was a lieutenant-colonel in the FSB, the successor organisation to the KGB. And Vladimir Putin headed the FSB at the time.

The court found him not guilty but in a chilling reminder of the power of the secret state, he was immediately re-arrested by Russian security forces and led away.

He spent almost a year in prison. On his release his friend, Yuri Felshtinsky, visited a Russian general to see if Litvinenko would be safe.

"He told me that Litvinenko committed treason and that in his organisation that is punishable by death," says Felshtinsky. "If he met him in a dark corner he would kill him with his own hands."

In 2000, Litvinenko fled to the UK with his family. He set himself up as a security consultant in London, advising businesses on investing in Russia. He did paid security work for the millionaire Boris Berezovsky, who was also a fierce critic of Vladimir Putin.

When Litvinenko worked for the FSB in Russia his job was to report on the Russian mafia. In exile, he used his old knowledge to help the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6. He used to meet his MI6 handler, "Martin", at a café in Waterstones bookshop in Piccadilly.

MI6 encouraged him to work with intelligence counterparts in Spain. In a rare interview, the Spanish anti-mafia prosecutor Jose Grinda explained why the Spanish wanted to work with Litvinenko.

Grinda, who once briefed the American government, in secret, that Russia was a virtual "mafia state", says: "We had targets in Spain that had been targeted before by Litvinenko. We needed him because he knew them, because he had fought against them, because he had investigated them."

A confidential document obtained by the BBC shows how the Spanish were closing in on the Russian mafia operating in Spain. The document contains the transcript of an interview with an alleged member of the mafia who seemed to be willing to act as an informant. The man claimed that the strength of the mafia would remain undiminished while Putin was in power. A short time after making this statement, he was killed in a mysterious car crash.

"We have confirmed links between Russian criminals and members of the Russian administration, of the Russian prosecutor's office, of the Russian army, and even members of the Russian government," Grinda says.

Front cover of the book Litvinenko co-authored

However, a very well-placed source with a close understanding of the thinking inside British intelligence says that this work for Western agencies did not get Litvinenko killed. MI6 assessed that he was murdered because he crossed two "red lines" when he made direct and highly controversial allegations against President Putin.

The first red line concerns a book he co-wrote called Blowing Up Russia about a terrorist attack in Moscow in September 1999. Chechen separatists were blamed.

Sensationally, Litvinenko claimed that Russia's own security services carried out the attack to give Putin the cover to launch a new Chechen war. Some 300 people had died.

His co-author, Felshtinsky, stands by their conclusions and says: "This [attack] helped Putin…the reaction of the population was we now have to have a strong leader."

The Kremlin has denied this completely in the past.

The second red line concerns an article Litvinenko published on the internet in July 2006, four months before he was murdered.

Litvinenko made some wild allegations. He claimed the Russian president was a paedophile, partly based on television footage of Putin kissing a boy's stomach. It was a scandalous claim. Putin claimed "there was nothing behind it". The Russian president told the BBC: "He was very sweet. I just wanted to cuddle him. Like a kitten. And it came out in this gesture."

Boris Berezovsky outside University College Hospital on the first anniversary of Litvinenko's death

Nevertheless these were dangerous allegations to make.

Marina Litvinenko has fought hard get the facts out into the open. She says: "I just promised to Sasha one day people will know truth about him."

In 2014, eight years after her husband's murder, she succeeded in her battle for a public inquiry. Ministers had refused in 2013. The inquiry chairman, Sir Robert Owen, has already said there is a prima facie case that the Russian state was responsible for the murder. He will report to the government on his findings by the end of the year.

Officially, Russia continues to deny any involvement in the murder. Andrei Lugovoi was made a member of Russia's parliament in 2007 - giving him immunity from prosecution - and just this year Putin awarded him a medal for services to the motherland. He now has his own TV show called Traitors. He organised a lie detector test in Russia to prove his innocence.

The other prime suspect, Dmitry Kovtun, is now a business consultant in Russia. He was due to give evidence to the public inquiry this week, but - at the last minute - pulled out. He said he had been unable to get permission from Russian authorities.

The inquiry will now hear secret evidence from intelligence agencies in special closed sessions.

It will report back at the end of the year and, until then, the mystery will rumble on.

The Newsnight report aired on Monday 27 July at 22:30 BST on BBC Two. Watch Richard Watson's full report here, external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.