Would Chinese-style education work on British kids?

- Published

The Chinese education system - with its long school days and tough discipline - tops global league tables. But how did British pupils cope when five Chinese teachers took over part of their Hampshire school?

For the BBC documentary Are Our Kids Tough Enough? Chinese School, an experiment was carried out at the Bohunt School in Liphook. Fifty children in year nine had to live under a completely different regime - one run by Chinese teachers.

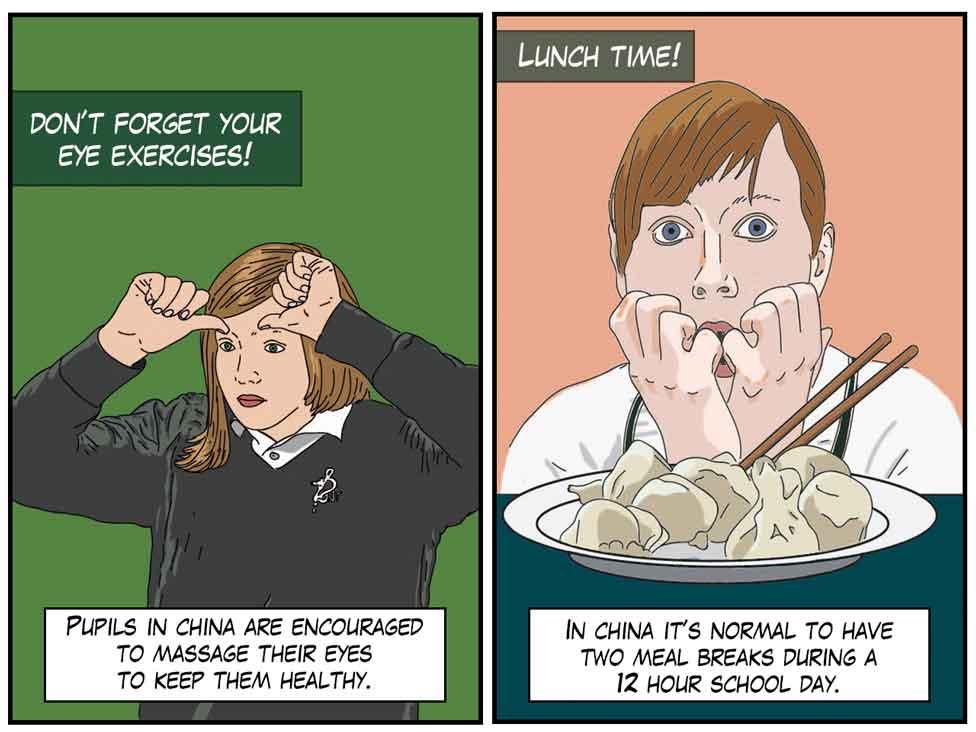

For four weeks, they wore a special uniform and started the school day at 07:00. Once a week there was a pledge to the flag. Lessons were focused on note-taking and repetition. Group exercise was undertaken. The pupils had to clean their own classrooms. There were two meal breaks in a 12-hour day.

Neil Strowger, headteacher, Bohunt School

In Shanghai last year, I had seen the incredible commitment of the students, enormous class sizes and immaculate behaviour. I had also witnessed PE lessons where the students stood in groups chatting, as PE was considered neither important nor a respite from the interminable monotony of the Chinese classroom.

In early spring, parts of my school were taken over. The Chinese flag was flying proudly over the sports field.

I had met the Chinese teachers at dinner shortly before the project began and was impressed by their determination.

But as early as the second day reports were coming in that the pupils were behaving badly - disengaged with the lessons, chatting and not listening to their teachers.

Chinese teaching methods were on a collision course with teenage British culture and values. Our pupils are used to being able to ask questions of the teacher - they expect their views to be considered with respect.

Furthermore, British pupils expect to have variety in their learning. They are not used to being incarcerated in a large group and in the same classroom studying a very narrow curriculum.

Headteacher Neil Strowger

As the weeks passed, thanks both to the support of Bohunt's pastoral staff and a slight shift towards a teaching approach more recognisable to our pupils, behaviour improved.

Perhaps as a result of the amount of time spent together, teacher-pupil relationships got better and some pupils began to express a preference for the Chinese style.

They liked having to copy "stuff" from the board as they thought this would help them remember it. Some more able pupils also liked the lecture style of the Chinese classroom.

What have I learned from the experiment? I believe that a longer school day would have value for our pupils and that teachers should not on occasion be afraid of delivering monologues in the classroom.

It is, however, abundantly clear to me that Chinese parents, culture and values are the real reasons that Shanghai Province tops the oft-cited Pisa tables rather than superior teaching practice.

No educational approach or policy is going to turn back the British cultural clock to the 1950s. Nor should it seek to.

Pupils are shown how to do eye exercises

Rosie Lunskey, 15, a pupil at Bohunt

I'm a normal teenager - I like my sleep and my freedom. But I traded it all in for more school than sleep each day, for four weeks with pushy teachers, all while wearing a completely atrocious tracksuit for almost 12 hours a day.

The project wasn't what I expected - I had envisioned something like normal school but maybe with a little more homework or a silent classroom.

That is most definitely not what I got. It felt like we had no say in our education and what the teachers said went.

Acting like robots was the right way to go. For me, it was something I found difficult to get used to. I'm used to speaking my mind in class, being bold, giving ideas, often working in groups to advance my skills and improve my knowledge.

But a lot of the time in the experiment, the only thing I felt I was learning was how to copy notes really fast and listen to the teacher lecture us.

One of the hardest things to deal with was different expectations of me as a student. It felt like we had to always be the best. That there was no longer any point in trying if you weren't going to be top of the class. Only the scores on tests mattered.

The classroom environment felt stressful and enclosed. When you have 50 other pupils in the room it's hard enough to concentrate without being made to feel as if you are competing against them all the time.

Science was particularly challenging. On one of the first days we were having the normal, slightly boring lectures from Ms Yang. Then we were given questions to answer on the subject and I understood nothing. I hadn't realised I would be this self-conscious, not being able to pick up a new topic at such speed and it got to me.

Pupils get ready to learn about fan dancing

I felt stressed out sitting in my lesson completely muddled. It was awful knowing I not only had my peers watching me, but the cameras too. I felt stupid and just utterly pulled under by the weight of everything. The Chinese teachers think the pupils in their classes are like bulletproof sponges, sucking in information yet conveniently ignoring the fact they are tired and very bored.

However there were definitely some good bits. I loved learning about fan dancing and Chinese cookery. These were certainly welcome distractions from dull lectures about Pythagoras's theorem and English grammar. I shall always remember trying out Chinese-style education - it was one of the most interesting months of my life.

Simon Zou, who taught maths and acted as form teacher

Simon Zou

I'm grateful that I could take part in the entire experimental project. It taught me a lot.

As a form teacher, I successfully introduced Chinese classroom management - where the class is a unit.

I established a class committee and routines for students on duty. Leaders were selected for each class activity. This allowed the students to bear responsibility, as well as to exercise their leadership, communication, cooperation and organisation skills.

I believe if we give students a stage to perform, they will surprise us.

Originally I was confident about my teaching method, but at Bohunt I encountered unexpected problems. Some of the students found it hard to adapt. When I first introduced Pythagoras's theorem, I decided to let the students find the proposition, prove and apply the theorem. That process is an important feature of maths teaching in China.

But a lot of students said they found it unnecessary to prove Pythagoras's theorem - knowing how to apply it was enough.

I became more familiar with the British students' learning habits but I insisted on my ways of teaching.

I introduced the Chinese Ring Puzzle to the students. I brought 70 puzzle pieces from China. I gave every student one puzzle to solve as an exercise, and I told them to keep it as a small gift from me. Unfortunately after the evening study session, some students left the ring puzzles on the desks, some even left them on the floor. The empty boxes were all over the floor. When I was doing the routine classroom inspection that evening, I felt very embarrassed.

Another thing I remember is that one afternoon in the third week, a boy named Joe fell down in the classroom and hurt his hand. He was crying. After the school doctor's examination, he was given some ice packs and advised to go to hospital.

When Joe's mother and younger brother were picking him up, one little thing impressed me in particular. Joe was carrying a heavy bag on his other side, but he didn't request us to help. Joe's mother did not offer to help him carry the bag, nor did Joe ask for help. Even when Joe's brother tried to help him carry his bag, Joe refused. I wonder if this is the result of the British education, that trains the children to become independent. This makes me think a lot.

Find out more

Take a look at an online comic of a day in the school that was taken over by Chinese teachers.

Are Our Kids Tough Enough?: Chinese School, is broadcast on Tuesday 4 August at 21:00 BST on BBC Two (not Scotland) or on 6 August at 20:00 in Scotland. The second series is broadcast on 11 August, or 13 August in Scotland. You can catch up via the BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.