Ferguson: The other young black lives laid to rest in Michael Brown's cemetery

- Published

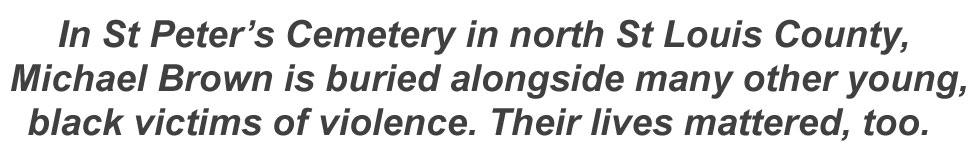

There is still no headstone in the place where 18-year-old Michael Brown Jr is buried.

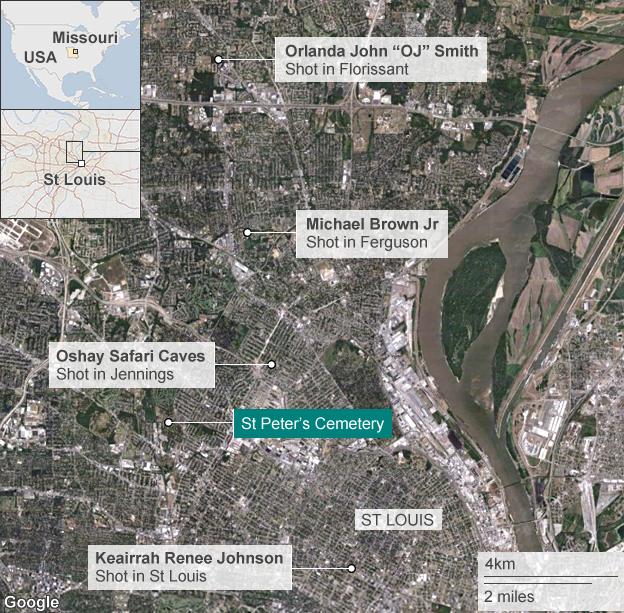

Those who wish to pay their respects have to ask for a map inside the office at St Peter's Cemetery, a verdant swatch surrounded by a low stone wall in the middle of urban north St Louis County. From the gates, visitors go straight, down a slight slope, make a right at the flower planter, pull over and walk a few short paces to section 10, block F, lot 12, grave number four, where the dirt has settled over the past 12 months and the grass is beginning to take root.

There's a cement base on the spot with the initials "MB" spray-painted on it in orange. The permanent monument is supposed to be installed any day now.

One year ago this August, former Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson shot Brown, who was unarmed, six times. His body lay in the street for four hours. In November, the St Louis County prosecutor announced there would be no charges for Wilson. In response, protesters hit the streets and vandals torched local businesses.

The movement that rose around Brown's death was held together by the idea that "black lives matter" - that the lives of African Americans should not be so easily snuffed out, and that their deaths should not go unpunished.

Directly across from Brown's grave is another that, according to the small stone marker, belongs to Jarris Brown. Michael and Jarris are not related. However, some quick arithmetic reveals that Jarris, like Michael, also died young, at just 16 years old.

The two boys are buried feet to feet, facing each other across their row. Jarris Brown's gravestone is embedded with a colour photograph of him - he's beaming, with a thin moustache and black hair to his shoulders.

"Loving son and brother," the inscription reads.

Photographs on monuments, either computer etched or pressed into ceramic, became a popular trend here about eight years ago, according to the superintendent of St Peter's.

If one walks in any direction away from grave number four, there are many more pictures of black men and women who died in their teens or early 20s. Some are grinning in school portraits, or giving the camera their most serious expression. Some stones include a baby picture, or a composite photo of the deceased with their children. One marker is etched with a photo of the young man's beloved truck.

Within a roughly 30-metre radius of Michael's grave there are at least 15 homicide victims. The youngest was a 15-year-old. Most of them were shot. There are also deaths by suicide, cancer, car accidents, but for those under the age of 30, the predominant cause of death is homicide.

Jarris Brown's death was an accident - a friend told police that he found a gun tossed in an alley, then playfully pointed it at the younger boy's head.

The friend went with him to hospital, and so his is one of the rare cases police closed. Most of the homicide victims lying here still have open files with St Louis' city or county police departments.

No-one has been charged. There's almost no information about what happened beyond a couple of lines in the local newspaper.

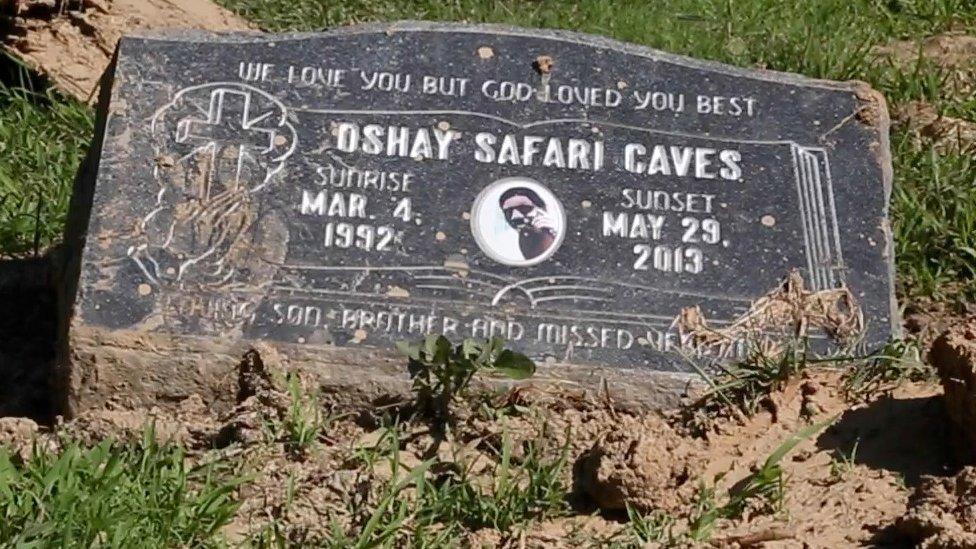

Oshay Safari Caves has one of those photos in his headstone - a black and white picture of him with dark eyes and thick brows, a slight afro puff, grinning with a mobile phone up to his ear.

Visiting Oshay at St Peter's Cemetery

His mother, Marie Ann, picked it because she says he loved to talk on the phone. He was only 21 when someone shot him in the head just a half a block from her house. His killers were never caught.

"I just wish justice would be served, because this right here is hurting me real bad," she says. "Every day I think about Oshay. It's hard for me to deal with. I go to the cemetery every chance I get."

Both Oshay Caves and Michael Brown were young, black men living in north St Louis County. They both dreamed of becoming famous rappers. And according to Marie Ann, Oshay also laid in the street for hours before an ambulance finally took his body away. She, too, remembers a trail of blood on the pavement.

In the early days after Brown's death, social media focused on the notion Brown had been trying to surrender, that he had had his hands up or been running away when the shots were fired. The injustice seemed clear, a young man, recklessly gunned down, his killer unpunished - on paid administrative leave, in fact.

As time went on, the idea of justice became more complicated.

Supporters of Wilson referenced the security footage of Brown pilfering some cigarillos at a convenience store and manhandling the clerk just prior to the incident. Opponents pointed out shoplifting is not an offence worthy of execution.

After two separate inquiries, the officer who shot Brown was found to be acting within the law. A St Louis grand jury declined to bring charges and a US justice department investigation, external concluded "Darren Wilson's actions do not constitute prosecutable violations". They cited "no credible evidence" that Brown had his hands up, and in fact found evidence of a struggle between the two.

But another justice department report, external found that Wilson was working within a system plagued by inequity and unfair practices. The citizens of Ferguson, where the average per capita income is $21,000 (£13,500), were routinely and repeatedly stopped and fined for minor transgressions that filled the city coffers - and though African Americans made up 67% of the population, they constituted 93% of the traffic stops.

The report was also filled with stories from black residents about how minor traffic tickets could turn into jail time for failure to pay, and about the police department's "pattern of unconstitutional stops". It painted a portrait of a city populace straining under the weight of racial bias and classism.

Michael Brown's death started a long conversation that's continued after the deaths of Tamir Rice and Walter Scott and Sandra Bland - about institutional racism, police brutality, respectability politics, body cameras, inherent dignity, militarised local law enforcement, school segregation and what justice looks like in the face of all those elements. The Black Lives Matter movement has grown and spread.

Recent protests have focused on deaths involving police, but for many of those buried in St Peter's Cemetery, their stories call back to the original idea that first drew people to the death of Michael Brown - young people, recklessly gunned down, their killers unpunished.

What happened to them goes to the heart of mistrust of police and communities shattered by tragedy, inequity and hopelessness.

Their families are left without justice, without a movement or a voice. Their children simply disappear.

"People out here are reckless," says Morgan Brionna Evans, Oshay Caves' sister. "They feel like they have nothing to live for."

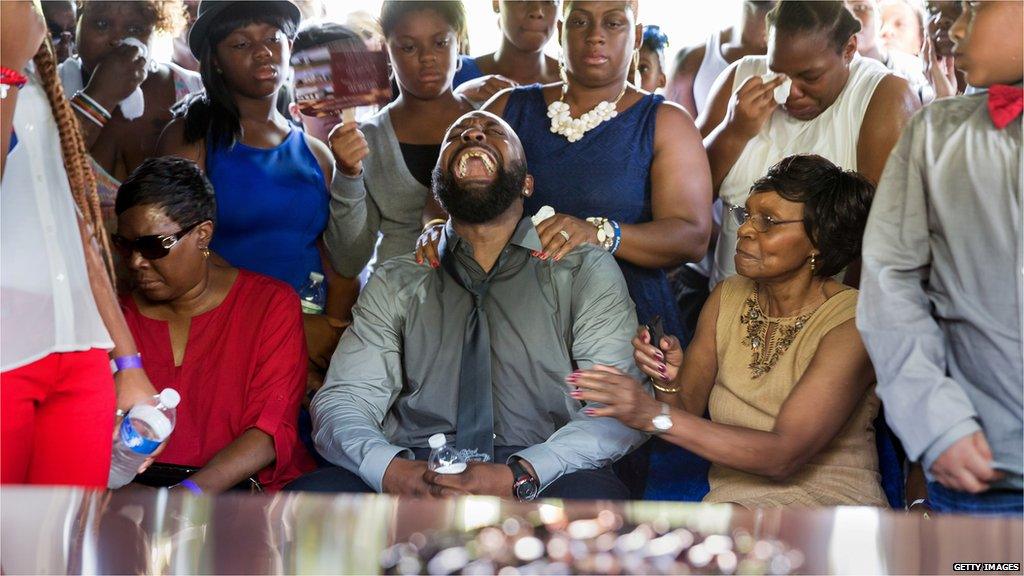

This is what he tells a group of about 10 teenagers in a community college classroom in St Louis in mid-July. His appearance has changed little over the last 12 months - his beard is longer, and the tense mask of grief has relaxed some. Even though he says people in the neighbourhood needle him about being "St Louis famous" and ask him why he doesn't wear rings and chains, his uniform is still a T-shirt and jeans. Today it's a black shirt covered with photos of black men and boys killed young - from Emmett Till to Trayvon Martin.

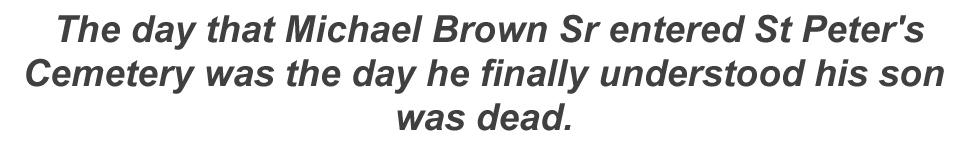

"I don't know if y'all seen that picture - at the burial, when they was lowering him and I yelled out," he says, referring to an iconic photo taken at the moment Michael Jr's casket began descending.

"That's actually when it became real to me. Everybody was like, 'He's not showing no emotions.' I was in a daze. But when I knew he was in there and this was dropping in that ground - I knew it was a done deal."

Brown Sr and his wife Cal turned up at this meeting of the Sweet Potato Project - a summer programme that teaches teenagers the basics of farming and entrepreneurship - for an impromptu, informal question and answer session just a few weeks before the anniversary of Brown Jr's death.

The teens ask him how hard it was to restrain himself the night St Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCulloch announced there would be no charges for Darren Wilson.

"I can't tell you what all was going on," he says. "It was that bad."

He tells them how angry he was when a Chicago artist recreated the scene of his son's death, complete with a life-size Michael Brown dummy lying face down on the gallery's shiny floor. He talks about how despite the advocacy he has become involved with after the death of his son - founding a non-profit called Chosen for Change, helping ex-offenders get record expungements and improving community-police relations - he is still filled with rage.

"The whole thing has me torn. I'm very mad, angry, pissed off," he says. "Sometimes I feel that it's built for us to fail, period."

Michael Brown Sr in 2015 (photo by Getty Images)

Brown Sr doesn't go into what "it" is that is built to ensure the failure of young African Americans in St Louis, but it's easy to guess. The region ranks high on the list of many indicators of racial inequality.

About 30% of blacks live in poverty, compared to 8.3% of whites. Blacks are almost three times as likely to be unemployed. The region is split geographically along racial lines, with most African Americans living in the northern parts of the city and county.

Those areas also have some of the region's highest rates for death from cancer and heart disease, for poverty and high school drop-outs. According to ProPublica, external, almost half of black children in the St Louis County area attend school districts that have been downgraded from full accreditation by the state, as opposed to one out of every 25 white students.

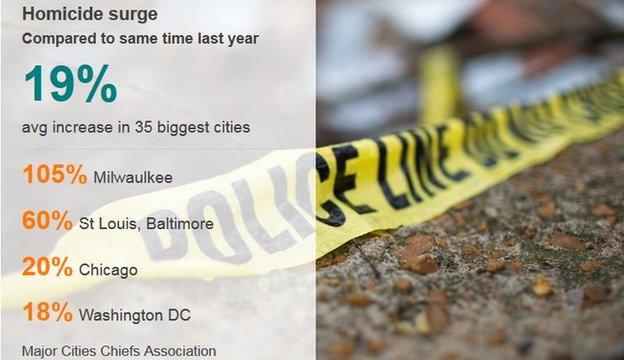

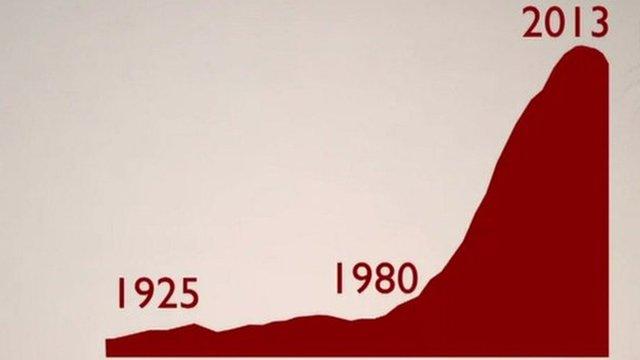

As homicide rates rise around the country, the vast majority of the victims are young black men. Blacks in St Louis are 12 times more likely to be murdered than whites. So far in 2015, there have been 116 homicides, which is at least 50% higher than it was at the same time of year in 2014.

The number of victims jumped from 120 murders in 2013 to 159 in 2014. While that may be new for the city, what has been true for years is that the state of Missouri has the worst rate of black homicide victimisation in the country - twice the national rate for black victims and seven times the overall national rate.

Brown Sr doesn't dive into all those numbers, still the students just nod as if it is a given that the odds are stacked against them. The discussion closes with Cal inviting the class to attend the events they're planning for the first anniversary of Michael's death.

"If any of you have loved ones that you've lost we're having a memory parade," she says. "You can honour your loved ones in joining us,"

"It's not just about Mike. You know, he opened everybody's eyes, but it's not just about him. We want to honour everybody who has been lost, whether it's to a police man or just senseless crime."

While those killed by police have captured the nation's attention, "senseless" homicides often merit little more than a line in the local crime blotter or a two-minute TV news bulletin. We know little about the victims - their names do not become hashtags.

"This is systemic. This idea that black people are 'less' - that it suffuses everything in our culture in America," says Jesamyn Ward, author of Men We Reaped, a memoir about the lives and deaths of five young black men she knew growing up in Mississippi - including her younger brother.

"Every time something like this happens I think about my brother and I think, 'These are somebody's sons. These are somebody's brothers.' In some cases these are people's fathers…They're human beings."

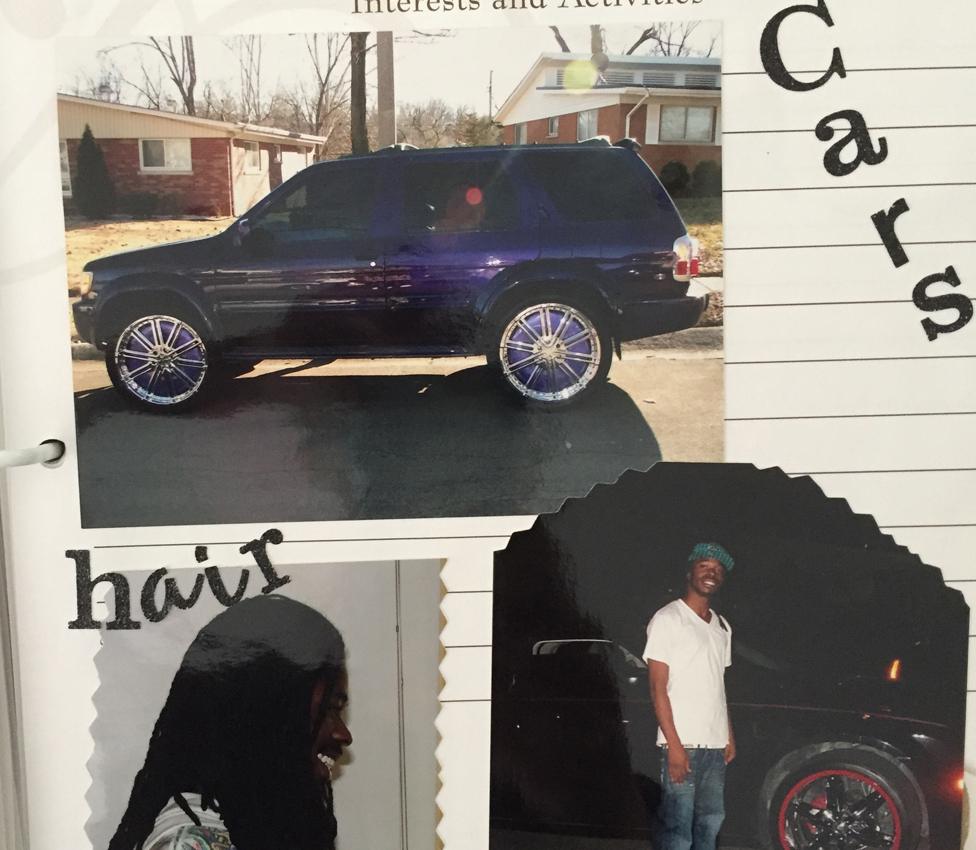

"Ma!" Orlanda "OJ" Smith called to his mother after pulling into the driveway of her tidy rambler on a quiet cul de sac in Florissant. "I got something to show you."

When Jennifer Smith walked outside, she saw her old Infiniti SUV - which was once beige - sitting in her driveway, now a gleaming candy purple with huge silver rims.

"He loved cars, he loved clothes, he loved to dress," she says. "Purple's my colour, so he liked purple, too."

Orlanda doted on his cars, a passion he inherited from his father and grandfather, even sacrificing a brand new pair of Gucci shorts in order to sew his own headrest covers. But he loved the truck in particular; so much so that his mother decided it should be on his headstone.

"He was just finding his way as an adult when all this happened," she sighs. "Everybody really loved him."

Jennifer met Orlanda's father in high school, but they didn't get together until after she'd returned from college and he got home from the Army. He was a bricklayer and Jennifer was a retail manager. OJ was their only son, an easygoing little boy who was riding a bike without training wheels at two years old and still in nappies.

After OJ was born, however, the marriage began to deteriorate. After the split, OJ was on his own most afternoons after school, checking in with his mom by pager. As a latchkey kid left to fend for himself at mealtimes, he became a pretty good cook.

His specialty, according to his friend Alicia Essary, was bacon mac and cheese, which he made by cooking the bacon slowly, on low heat until it was crispy enough to fold in paper towels and smash into little pieces with a meat tenderiser.

"It had to be real bacon. I brought Bacon Bits over there and he told me, 'No, no, no,'" she recalls.

Jennifer was dismayed when Orlanda announced the summer after his junior year that he wasn't going back to high school, but he got jobs working at Rally's, McDonald's, Steak 'n Shake. He was also selling marijuana, though friends say he wasn't involved in anything more serious than that, even though he ran with a rough crowd at times. He had no criminal record.

"Florissant is not the place to be," Essary says ruefully. "There's nothing in Florissant but drugs and jail."

Something began to shift for OJ as he entered his 20s. After years of chiding, Jennifer finally persuaded him to get his high school diploma online.

"He was so proud of that, he couldn't wait to show my mom," she recalls after he received his degree.

He accompanied Jennifer to a local vocational college (the same where Michael Brown was supposed to study, which has been criticised for misleading students, external), where she said he signed up for courses in plumbing. According to Essary, he'd completely stopped selling drugs.

"He was giving up the crazy life and trying to do the right thing," she says.

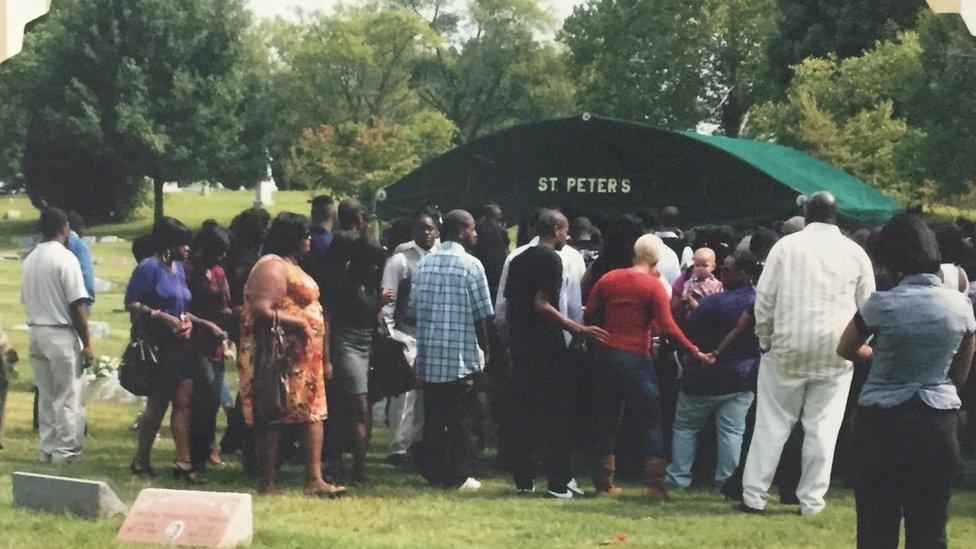

Mourners at OJ's funeral

In the weeks before his death, OJ asked to move back home. Jennifer welcomed him back to his room in her finished basement. He was supposed to start school the following month.

In the early morning hours of 16 September 2009, Jennifer opened her garage door and saw three masked men charging up the driveway towards her. When they demanded to know where OJ was, Jennifer feigned ignorance. But his distinctive car gave him away.

"Where is the money?" she remembers them screaming as they pushed her towards the basement door. When they threatened to kill her, OJ opened the door to his room and the basement exploded in gunfire.

"You can go call the mother------- ambulance," she says one of the men said, then turned and ran. But it was already too late.

"I never slept at that house again," she says.

St Louis County Police investigated OJ's murder, but after several years and several pushes in the local media for information with thousands of dollars in reward money available, no one has ever been caught. A letter from a tipster in jail led to nothing. OJ's case eventually got reassigned to a different detective and Jennifer stopped calling to check on the progress.

"I haven't given up. I feel like eventually something will come to light," she says.

Amid a rising in homicides, the number of cases "cleared" or in some way resolved whether it be through the death of a suspect or an actual arrest, is dropping. In St Louis, it's currently at about 40%, down from an average yearly rate of 58%.

In 2015, for example, the city police have cleared 38 homicides, issuing charges in 21. There were eight white homicide victims and 108 black victims.

By numbers alone, the police have cleared at least three times as many cases with black victims as with white. That still leaves the vast majority of the cases with black victims open, which has contributed to a perception in the community that the police care far more about white victims.

Homicide surge

Compared to same time last year

19%

avg increase in 35 biggest cities

-

105% Milwaulkee

-

60% St Louis, Baltimore

-

20% Chicago

-

18% Washington DC

Homicide detectives insist race has no influence on their investigations, and St Louis Metropolitan Police Chief Sam Dotson points to the same tapestry of socioeconomic ills as a source for the high murder rate, as well as the abundance of guns on the street.

"If this were a disease or an epidemic, then millions of dollars would be funnelling into research. If this was a cancer or something like that - we don't have the same sense of urgency around it," he says.

"It's poverty, lack of employment opportunities, lack of education opportunities. Jobs aren't a law enforcement issue, substance abuse isn't necessarily a law enforcement issue. Except law enforcement is the front line to address this."

Police Chief Sam Dotson (centre-right) speaks to reporters

Other factors that contribute to the lower solved rate are a common refrain - uncooperative or scared witnesses. Communities who would rather even the score than use the criminal justice system. Victims who are involved in criminal activity. These are the types of murders that seem to receive the least attention.

"The narrative in which someone's morality and stereotypical ideas around morality can be deployed to invalidate their humanity or right to equal treatment - we're very familiar with that," says Jelani Cobb, a staff writer for the New Yorker who has written extensively about these issues. "Don't be surprised if black people, too, don't think those dudes' lives matter who died in these types of ways."

OJ's headstone in St Peter's is one of the most elaborately decorated and carefully tended. It's always surrounded by bunches of purple flowers. On his birthday, Jennifer tied a Mylar balloon to a stake and wrote him a card she carefully placed in a Ziploc bag to guard it from the rain.

She's left pictures of a little boy named OJ Jr there too - when Orlanda died, his girlfriend was two months pregnant. Orlanda Jr is now a precocious five year old whose favourite toy is a bright purple SUV.

"I lost a son, but I gained a daughter," Jennifer says of her relationship with the mother of OJ's son. "I thank God for that. I don't know how it would be if I didn't have him."

Keairrah Johnson may have been a "busy and bossy" workaholic in her parents' eyes and a "party girl" to her friends, but they all remember her laugh - a loud, high pitched giggle.

"Who laughs and thinks it's funny when your car stops on the bridge because you ran out of gas?" says her friend Whitney Tyler. "The gas meter was broke so Keairrah didn't know when to put gas in it. This particular time she misjudged it, the car started getting real sluggish on the ramp then it just stopped. She just fell out laughing."

A teacher's pet since grade school, Keairrah had an associate's degree from St Louis Community College and worked multiple jobs, hoping to eventually study law. By the age of 22, she owned a duplex in north St Louis city which she rented out to tenants. She could wire a house and fix the plumbing.

She also had a mischievous streak - she had a fake ID and loved to go clubbing well before she was 21. She was also a bit secretive about her personal life.

"Her mentality was that of a man. You're not really going to catch on to her feelings," Tyler recalls.

That all seemed to change when she met her boyfriend, 27-year-old Marquis.

"Everyone knew it was different. They had more of a friendship that ended up turning into a relationship," says Tyler. "Keairrah had found somebody who was on the same level as she was mentally and it just worked."

On 3 February 2010 Keairrah needed to get her property whipped into shape for some new tenants. So she recruited a group of people, including her father Arthur and his wife, her brother Laron, and Marquis to help her. The days were short then, and by the time they finished it was already getting dark.

Arthur and his wife left the property first, but within minutes, he got a frantic call from Keairrah's brother. He'd been riding in a car behind Keairrah and Marquis when another car pulled up beside them and opened fire. Police would later describe the weapon used as an AK-47. The assailants sprayed the car with bullets, and took off.

Arthur made it to the scene before the police, pulled Keairrah out and began administering CPR.

"He's her daddy," he remembers Laron yelling as the police pulled Arthur off Keairrah and pushed him into a police car.

The stretch of MLK Drive in St Louis where Keairrah was killed

Both Keairrah and Marquis died that day. They're buried next to each other in St Peter's. The general consensus seems to be that someone was targeting Marquis and Keairrah got caught in the middle. No-one has been arrested. It's been over five years, but in her mother's darkened living room the pain is fresh.

"It's a cold case murder. That's all it is. They haven't been doing no further investigation, they just threw my daughter's case on the back burner," says Sonya Davis, her voice a mixture of sorrow and anger. "She was just as important as Megan Boken."

Boken was - like Keairrah - an innocent victim, shot and killed in a brazen daylight robbery in 2012. She too was known for her academic drive, her laugh and her sense of humour.

But Boken was white - a blond-haired and blue-eyed beauty - and the former St Louis University student has become a symbol of unequal justice for the African-American community.

The investigation into her death was aggressive, resulting in multiple arrests related to the death of Boken and other crimes that occurred around the same time.

One man eventually pleaded guilty to her murder and is currently serving a life sentence. Another man produced an airtight alibi for the time of the murder, but became ensnared in the criminal justice system for years on separate charges until the state's case against him fell apart.

"They solved her case like, bam," says Arthur in a low voice.

"We investigate every crime with as much effort as we can, regardless of the background of the victim," says Captain Michael Sack, the head of the St Louis police's crimes against persons division.

"We're accustomed to criticism, but we want to be able to say we've done the best we can."

Davis used to attend a candlelight vigil held every year to remember the city's homicide victims. She no longer sees the point. All she cares about is the case being solved.

"I hope someday that I can lay eyes on the person who took my child away from me," she says. "She had a lot to live for."

For Tyler, her friend Keairrah's unsolved murder illustrates something she already learned first-hand while clerking at the St Louis city courthouse.

"Only 40% percent of the people get caught who killed somebody. You don't get your hopes up," she says. "OK, it's just somebody else that's just dead. You hate to look at it l like that, but that's the reality of it."

"That's where the lack of communication comes in terms of not wanting to talk to the police. It's not, 'I'm not going to snitch'. They just don't feel like the justice system is going to prevail. That's why a lot of people think they need to go out and take care of it themselves."

Marie Ann Caves flips slowly through a stack of photos of her son Oshay when he was younger, a toothy, round-headed kid with big dark eyes.

"This is Oshay when he was in grade school," she says, pointing. "He loved to clean and asked the teacher for a broom so he could sweep the classroom. He was very neat."

To her left is a shelf stacked with photos of her six kids and their high school diplomas from Jennings Senior High School. Oshay was never an A student - he was diagnosed with various learning disabilities at a young age - but Marie Ann says whenever he was failing he knew how to ask for help, and managed to pull up his grades to about a C-average.

Who was Oshay Caves?

"Oshay was just the love of my heart. He said when he got big into the rap game he wanted to take care of my family," recalls Marie Ann. "He loved everything 2 Chainz. I said, 'OK, Oshay, you're going to be the next 2 Chainz.'"

Like Orlanda Smith, Oshay smoked weed and hung out with friends who were involved in gangs. But even though his mother says they had issues with the Jennings police writing her kids tickets at every opportunity, he had no criminal record.

His family says he showed an affinity for homeless people, saving up his old clothes to give away, and using his disability check money to buy bags of burgers to hand out to anyone he saw roaming the street.

Oshay's sister Morgan Brionna Evans remembers when he started getting threatening phone calls from someone he once considered a friend. Her understanding today is that it was an argument over money.

On 29 May 2013, Oshay was staying with his girlfriend in downtown St Louis when he started getting calls from someone saying they were lurking outside his mother's house. Oshay took off in his car and as he neared his mother's home, someone opened fire. He was killed instantly.

The Caves told investigators exactly who they believed did it. Suspects were interviewed, but nothing stuck.

Visiting where Oshay was killed

Marie Ann says she has no idea who the lead detective on the case is. Meanwhile, Oshay's siblings move in the same social circles as those they believe are responsible. When Evans sees them in the same nightclub, she leaves. She can see what they're up to on Facebook.

Marie Ann and Morgan left the house in Jennings after it was repeatedly shot at, the bullet holes pocking the bricks with black marks. Recently, they took a ride to visit the old house and the spot where Oshay died.

"Oh my god," exclaims Morgan from the back seat. She is reading a post from her Facebook feed.

"According to Facebook, 22 minutes ago he was just killed. It don't state how and why and when… the person who was apparently involved in my brother's shooting."

A bullet hole near the site of Oshay's death

At the same time, Marie Ann receives a call with the same news, from her sister. The rumour - and that's all it is - is that the person the family strongly suspects was the gunman in Oshay's death was just shot and killed.

"Wow," Evans says. "Now his family is going through what we just went through."

Street justice, as it's sometimes called, is just one of the reasons that gun violence continues rolling through the same neighbourhoods with increasing momentum. According to Captain Sack, St Louis is not a city of organised gangs battling for turf or drug territory.

"It's, 'This guy owes me money.' Or 'He fronted me in front of these other guys, now I've lost face,'" he says.

The problem with street justice, as Orlanda Smith's friend Alicia Essary points out, is that it leaves the victim's family without any resolution. Violence begets violence.

"If the police don't take care of it, the streets will," she says. "Somebody knows who did it and they'll take care of it. But none of us will ever know."

Evans and Marie Ann Caves meet some of Oshay's brothers at St Peter's. There is no jubilation in news that Oshay's suspected killer may just have died. Morgan finds the man's Facebook page - the last image posted is him with his young daughter.

"I don't know how to feel," Morgan shrugs.

Chevis Caves, the eldest brother, remembers well the day Michael Brown Jr was buried. He came to visit Oshay's grave and noticed a freshly dug plot just a couple rows away. Mourners began pouring in from the front gates, heading towards him.

"This whole thing was packed, there were police everywhere, horses everywhere. This whole thing was surrounded," he says.

Chevis says along with several family members, he knows about seven or eight people his own age buried in St Peter's.

"Most of them got murdered," he says.

Oshay's family

Michael Brown Sr says he's still fighting for justice - now in the form of a wrongful death lawsuit against Ferguson, its former police chief and Wilson. But his son's death has opened a broader conversation about death in the black community.

It's a conversation that the country was not having a year ago, and it remains to be seen whether real societal change will follow, targeting and addressing the many factors that contribute to shootings happening with increased frequency in neighbourhoods like the ones in North St Louis.

"When people were saying, 'black lives matter', one of the things that made that appealing is the fact it was ambiguous. It could be related to police brutality, but it could also relate to the callous indifference with which we regard the abysmal homicide numbers," says the New Yorker's Cobb.

Standing around Oshay's resting spot in the punishing July heat, Marie Ann points to a stone she notices nearby with yet another picture of a young black man in the middle. She doesn't know it, but the marker belongs to another homicide victim, this one also shot to death in his car in 2013.

"That's a young guy," she murmurs.

Videos by Anna Bressanin

Production by Taylor Kate Brown

- Published14 March 2012

- Published14 July 2015

- Published25 November 2014

- Published26 November 2014