America's iconic war machine

- Published

The Memphis Belle IV with full payload on show at Barksdale - the plane took part in the first Iraq War

The most feared bomber plane of the 20th Century is still going strong after 60 years in service in the US military - from Vietnam to Afghanistan. And she will keep on flying until 2044. How does this 1950s behemoth survive in the era of drones and stealth aircraft?

We are sweltering in the Louisiana summer. The baking hot tarmac of Barksdale runway feels like burning coals.

A huddle of young mechanics - exhausted, perspiring - take shelter under the shady belly of a hulking, battered-looking bomber.

Its guts hang open. The battle-worn paint under the wings is peeling away to expose yellow primer underneath.

Her name is "Cajun Fear" - painted on her nose with a snarling alligator.

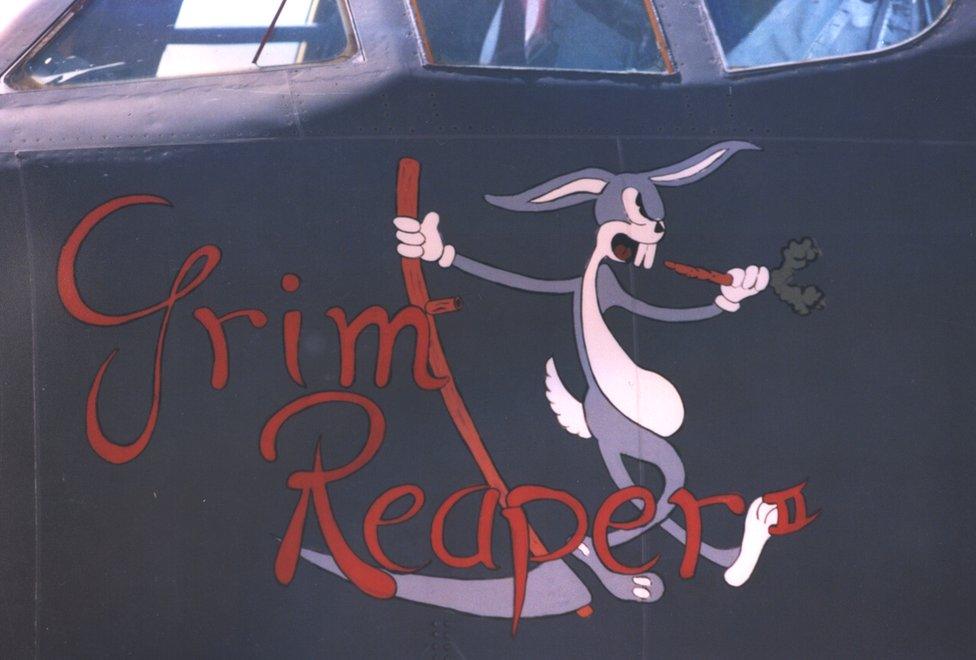

Parked alongside her: the Grim Reaper, Apocalypse, Global Warrior, and the Devil's Own, the pride of the 96th bomb squadron - the "Red Devils".

They call it "the Buff" - an acronym whose first three words are "Big Ugly Fat".

This bomber was built in 1960 - the year JFK won the US presidential election, Hitchcock's thriller Psycho was released in cinemas and the USSR successfully sent two dogs into space.

Two years later, in 1962, at a factory in Wichita, the last ever B-52 nuclear bomber rolled off the assembly line, fired up its eight engines, and took off to play its role in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Lasers, the moon landing and personal computers - all younger than the B-52

Today, more than half a century later - after Vietnam, two Iraq Wars and Afghanistan - the ol' granddaddy of the US Air Force is showing its battle scars.

The pilots joke that if you flew upside down "chicken bones from Saigon would fall out."

But these senior citizens still proudly patrol the skies for the United States. When the US wants to deliver a message, it sends a B-52.

In November, to Beijing's fury, two B-52 bomber planes flew near disputed islands in the South China Sea.

"It is a symbol of American might," says Capt Erin McCabe. "Wherever we go in the world, people take notice."

The US puts such faith in these historic machines that they will keep on patrolling the skies until 2044 - well into their 80s.

In the era of drones, stealth aircraft, and cyberwarfare, a chunky old behemoth sketched out on a napkin, external three years after the end of World War Two still strikes fear into the enemy.

"This plane is the iconic war machine for the United States Air Force," says Col Keith Schultz, 2nd Bomb wing vice-commander, who has piloted B-52s for more than 30 years.

"When we load these weapons, the world takes heed. It's always the first aircraft in there in a conflict. We knock down the door - and let all the other aircraft in to do their job."

"It's like a dump truck - nothing else has that type of range and capacity"

"Knocking down doors" in an aircraft this size - 159ft (48.5m) long, and with a wingspan of 185ft (56.4m) - is a team sport, performed by a crew of five.

Sitting downstairs in the dark, with no windows, targeting and releasing the bombs, is Capt Ryan Allen, a weapons systems officer ("wizzo").

"Think about the amount of political power this aircraft has," he says. "When an F-16 shows up in your country - big deal. But when a B-52 shows up… they start singing a different tune."

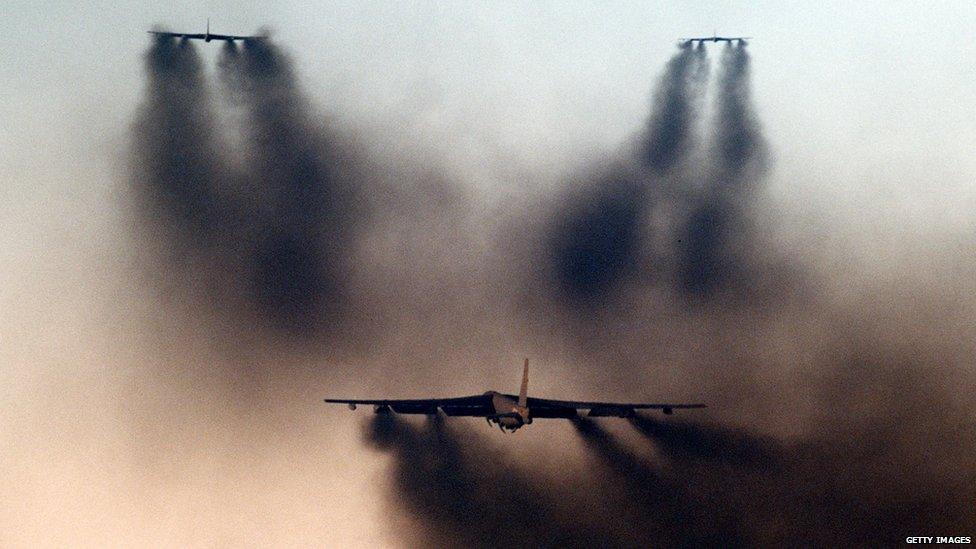

We hear a roar and look up. A dark bird is looming heavily over us, blocking out the sunlight.

Plumes of smoke from eight engines fill the sky and eardrums vibrate to a distinctive sound. Not just a rumble but almost a scream from the turbofans. "The sound of freedom" as Schultz likes to say.

Cruising at 650 mph at up to 50,000 feet (commercial airliners fly around 35,000 feet) the colossal bomber's 70,000lb payload includes hundreds of conventional bombs and 32 nuclear cruise missiles.

It can refuel in mid-air - giving it a potentially unlimited strike range. This created a "nuclear umbrella" for the United States during the Cold War, back in the era of Mutually Assured Destruction.

B-52 refuelling mid-air

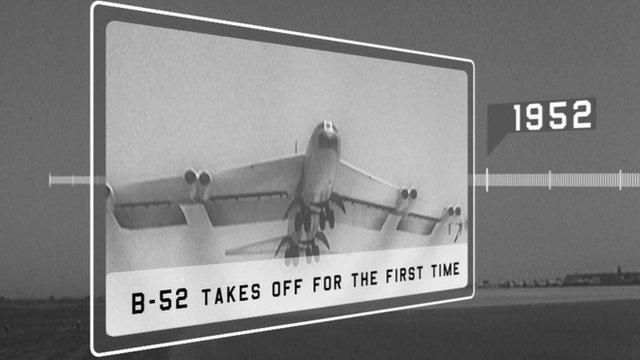

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

First flight: 1952. In military service since 1955. Planned to remain active until 2044.

A total of 744 B-52s were built with the last, a B-52H, delivered in October 1962.

85 planes currently active.

Designed to carry nuclear weapons but has never launched one in war.

Crew: five - aircraft commander, pilot, radar navigator, navigator and electronic warfare officer.

Wingspan: 185 feet (56.4m); length: 159 feet (48.5m); height: 40 feet (12.4 meters); weight: 185,000 pounds (83,000kg).

Range without refuelling: 8,800 miles (14,000 km).

"Those engineers who drew it on a napkin in Ohio that first night, I think they knew they had a sweet, successful architecture that was gonna last the duration," says Schultz.

"And in that era you're not talking computers - you're talking slide rules.

"They built in a lot of durability to withstand a lot of take-offs, turbulence. It's over-engineered - and that's its staying power."

Col Warren Ward, a veteran pilot of Operation Desert Storm, also admires the Buff's sturdiness.

"It's gonna bring you home," he says. "It's ugly but it gets the job done. Other aircraft have come along that were supposed to replace it. The B-1 was gonna replace it... didn't happen. Then the B-2… that didn't happen either."

The exterior of the aircraft has changed little since the 1950s.

But internally, over the years it has been refitted with computers and GPS/INS (Inertial Navigation System), external.

It may have been designed with just one thing in mind - to rain bombs from a great height - but over the years the Buff has been adapted to carry almost any weapon in the US inventory, including laser-guided cruise missiles, and to conduct low-level bombing raids in Afghanistan.

As enemy technology has advanced, so too have the defence and disguise tools employed by the electronic warfare officer.

Sitting upstairs, facing backwards with no windows, he or she uses radar jammers and false target generators to help the B-52 dodge anti-aircraft missiles and fighter jets.

"We're as big as a barn on the radar. We're not going to hide from anybody. So what I do is very important," says McCabe.

The pointy tip of the spear

Captain Erin McCabe, electronic warfare officer:

I first heard about the B-52 on the History Channel. Because it is historic. It's older than my parents.

Usually the first question I get - "Is that thing still flying?"

But that's the beauty - it's so old and the enemy is thinking about the new thing - not the old B-52 any more. So all our tricks are still viable. It's just as lethal as when it was first made.

Versatility is our strength - we can carry almost any weapon in the US inventory.

My favourite is flying low-level and feeling the percussions of the weapons.

It burbles the aircraft, and you can feel how fast they hit - boom, boom, boom - the loud noises.

I want to be part of the pointy tip on the spear - the first person out there to knock on the door.

But as enormous as the B-52 is on the outside, once you fold down the hatch and clamber up the ladder into the dark interior, it is anything but spacious. The crew rub up against each other with little room for privacy.

"The airplane was not designed for people. It was designed for bombs," says Ward.

He should know, having once made a flight that lasted 47.2 hours.

"We took off here at Barksdale, flew east… and landed at Barksdale again - all the way around the world."

And of course there are no creature comforts.

"You can't even stand upright, except on the ladder if you want to stretch your back. Though if you're creative you can sling up a hammock, he says.

The ejection seats are "like sitting on a concrete sidewalk".

And as for the odour… "It does not have a new-car smell," says Ward.

"You get in and it's hot and you're pouring sweat into your seat cushion.

"But then when you climb to altitude it's freezing, and your clothes are still all wet, and you shiver…"

To get an uncensored flavour of what it smells like to steer a 100-tonne hulk of 1950s design, it's worth reading the blogs of a former pilot, alias Major Kong, external, named after the bomb-riding B-52 commander in Stanley Kubrick's 1964 classic Dr Strangelove.

"Every B-52 I flew in smelled like stale sweat, piss and engine oil," he writes.

The "facilities" for the crew consist of a can with a lid on it, which sometimes leaks.

"And if you have to go the other way, it's the 'honey bucket'," laughs Ward.

"But he who uses that is banished forever. On that round-the-world flight we had a bet going - whoever breaks first buys the beers.

"We made it all the way to the Aleutian Islands before our co-pilot broke out in a sweat and bolted up.

"A voice came over the intercom: 'We have a winner!" Then everybody went full oxygen..."

So it's uncomfortable to fly in. Maybe it's a joy to manoeuvre?

You can forget that idea, says Ward.

"It is a pig to fly. It's a dump truck. I equate it to herding buffalo.

"You turn the yoke… nothing happens. Turn it again… nothing happens. You turn it the third time, and the first instruction is kicking in.

"It's not nimble. But you come to respect it."

From this sleepy corner of Louisiana, Ward took part in one of the longest and most devastating bombing raids of the 20th Century.

One night in December 1991, he was woken in the middle of the night and called urgently to the briefing room.

He and 56 other crew entered seven bombers - his was the Grim Reaper, with a painting of Bugs Bunny carrying a sickle on its nose - and flew 14,000 miles to Baghdad to drop a wave of cruise missiles, which obliterated Saddam Hussein's air defences.

A day-and-a-half later (35 hours) they landed again, without their wheels having touched the ground.

"Better Duck" - Col Keith Schultz with the bomber he flew to Iraq in Desert Storm

The global strike range of the B-52 also created a new phenomenon in warfare - a new kind of psychological experience.

"It's very unique, to fight a war thousands of miles away and return home to a normal lifestyle," says Schultz.

"And at 35,000 feet you don't hear the battle cries. You don't hear the 200lb bomb going off. If you sneezed you'd miss it."

Ward agrees: "I could wake up here in my own home, take off and fly to a war half-way across the world, come home and sleep in my own bed. That's a pretty strange concept in the whole history of war.

"I can reach out and touch my family, which is a beautiful thing. But you're conflicted because you can't tell them anything. You can't decompress."

Instead the pilots rely on their comrades for support.

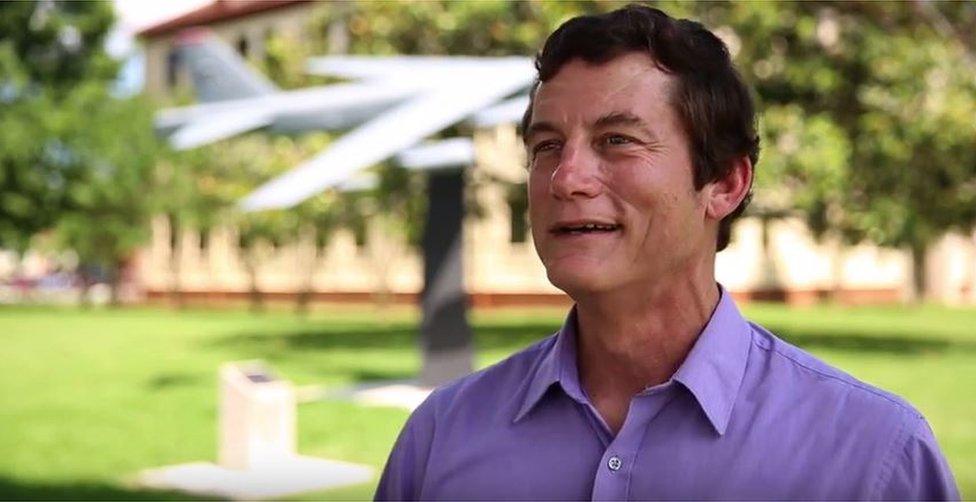

Capt Ryan Allen

"It's not like a fighter pilot mentality where you're invincible and you do everything on your own," says Allen.

"It forces you to co-operate. I wouldn't trade that camaraderie for anything else in the world.

"When we're dropping bombs on the training range there's always cheering.

"Usually we have a contest to see who gets the closest bomb. The loser buys the beers.

"It's awesome. It's a rush. We thump our chests a little bit."

This pride and affection for the beloved Buff transcends all ranks at Barksdale.

The engineers for instance have a tradition of "patting the aircraft as she goes", says maintenance crew chief Jacob Dunn.

"All our planes are 'shes'. It's just a superstition we have."

And what about the bombs - does he ever hug them, like Major Kong?

"Of course! Who doesn't wanna hug a bomb?" he grins.

He is joking… at least, I think he is. Crude gags and devilish humour are the oil that holds these crews together.

But don't let that fool you into thinking they are relaxed about their duties. They scrutinise and inspect every last bearing. "Is that a crack up there? No, just dirt. OK, phew!"

In this age of "smart" new devices which break and cannot be repaired, the remarkable endurance of a mechanical 1950s bomber - and the Air Force's "don't discard, reuse" mentality - feels almost heartwarming.

That is, until you remember the destruction it has wrought. Seen from the ground, 60 years of the B-52 is a very different story.

A child stands in front of the remains of US aircraft, including part of a B-52, shot down over Vietnam

Its future will include an improved weapons system, better data links for communications, and the re-engining of the aircraft to reduce fuel consumption.

But for the crews who fly it, it will still and always be the Buff. No technology can replace what makes it special, as Allen explains.

"I'm sitting in a jet that probably went to downtown Hanoi in the 60s, or shot cruise missiles into Iraq in the 90s.

"I'm sitting in an aircraft that's survived the ages and adapted to all kinds of mission sets… and it's still looking to go to 2040 and beyond.

"My kids and even my grandkids could fly it.

"That's awesome. That's huge."

That's a B-52.

Operation Secret Squirrel

Col Warren Ward (ret), deputy director of programming, USAF Global Strike Command:

I got into B-52s in 1988. Back then we had the Soviet menace, before the Berlin Wall came down. From my perspective, we just thought we were in a flying club.

I thought great - the government's paying me to fly and I'm never going to have to use it! There's no big Armageddon war coming.

Then all of a sudden Iraq rolls into Kuwait and the reality started sinking in... Oh my God what are we doing?

The squadron I was in - 596 Bomb Squadron - we got put on a mission called Senior Surprise. But that was classified so we had to call it something else. We called it Secret Squirrel.

We had a new cruise missile that was a variant of a nuclear missile.

While the rest went out into the field we stayed back in Barksdale. Our families asked, "Why are you staying back?" We couldn't tell them anything.

On the night of 15 January, we stayed up late watching the news, waiting. I remember going to bed at midnight, tired, and at 3am the loudspeaker comes on for all the Secret Squirrel crew to get into the briefing room.

I was tired, I don't wanna get up. The colonel is there - all the weather report, enemy warnings, where the bad guys are.

We took off at 6.30 in the morning. Seven jets taxiing out of the airport. I was in number three jet.

We fly non-stop from Barksdale to the Middle East. We never landed... 35.4 hours.

I'm not gonna stand here and act cocky. I was scared. I didn't know what I was getting into. It was the first time I'd dropped live ordnance against anybody.

We launched them cruise missiles from the airplane and when they go you think, "Somebody's gonna have a bad day."

The longest combat mission prior to that was the RAF flying Vulcans. We beat their record.

After 17 hours over there I was able to dial into the BBC on shortwave radio and find out what we did.

We asked you to share you thoughts - here are some of your emails:

David Meigh, Jakarta: I spent five years building irrigation systems in Vietnam for peasant farmers whose one million relatives were killed by these weapons of terror - old people, women and children. I have stood in craters made by them near Dau Tieng whilst our project had to clear vast quantities of unexploded bombs to build canals.

John McDonald, Nottingham, UK: About a million dead people have shared the B52 experience. They can't speak for themselves.

Dave Volker, Minnesota: I flew B-52s during the early 1970s. Stateside we stood ready to defend the US with nuclear capability. In South East Asia we flew combat missions over Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam while stationed in Thailand and on Guam. I accumulated 42 combat missions as co-pilot and pilot in command. I am proud to say that I flew these aircraft as a volunteer; I chose this aircraft and to fly it to defend the US. We faced down the Russian Bear and won the Cold War. We in the Strategic Air Command prevented a global apocalypse with one of the finest war machines ever made. Sometimes it takes a large and imposing sword to keep the peace.

Wayne, Wigan, UK: I was fortunate enough to maintain B-52G aircraft in Guam from 1988 to 1990. It was pretty mind blowing to later talk to my dad back home and to realise that some of the airframes that I worked on were the very same ones that he had maintained in the early 60s in Michigan. No surprise to me that they are scheduled to continue their mission for another 30 years.

Artem, London: Millions of people [have experienced B-52s] - these raids destroyed their countries infrastructures, killed their families and maimed them for life, something you clearly fail to make notice of.

Anonymous, Decan, Kosovo: I was blessed to live in the era of B52 and Nato who stopped ethnic cleansing of Albanians from Kosovo.

Alan, Essex, UK: In January 1991, at the start of the first Gulf War, I lived in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. We were woken in the early hours to the sound of B-52s flying over the house very low, on a long slow approach to land at the airport. The noise was unbelievable, but the impression of power was awesome. We knew then that the war had started. Over the next few days, I watched further streams of bombers on approach intermixed with Hercules C-130s and KC135 and KC10 tankers, using any one of the airport's three runways. After the uncertainty following the invasion of Kuwait we realised that the kingdom had massive support.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published13 June 2014

- Published13 June 2014

- Published24 December 2012

- Published9 December 2015

- Published9 December 2015

- Published27 November 2013