Dolphin Square: The UK's most notorious address?

- Published

Dolphin Square has long been a home to MPs, spies and other notables. It has been at the epicentre of a slew of scandals over the decades, writes Hannah Sander.

Two Union Jacks guard the entrance to a vast block of flats in central London. At the front, the giant 10-storey block looks out over the River Thames.

At the back, the redbrick flats overlook some artificial football pitches. This is Dolphin Square in Pimlico, south-west London, one of Britain's most extraordinary addresses for nearly 80 years.

In July, the bright interior of a Dolphin Square flat was the setting for leaked tapes that appeared to show Lord Sewel snorting cocaine with two prostitutes.

For long-term residents of the square, the consequent parade of journalists marching before their windows was a familiar sight.

Dolphin Square has had an unusually colourful history. During World War Two, "blackshirt" leader Oswald Mosley was arrested in his Dolphin Square flat and driven to prison. MI5's Maxwell Knight recruited Ian Fleming to the Secret Service from a flat a few doors down.

Charles de Gaulle based his Free France government in the square during the war. Two decades later the Soviet spy John Vassall was living in the square when he was arrested for treason.

Famous faces around the square: Ian Fleming; Princess Anne; Harold Wilson

Winston Churchill's daughter Sarah was evicted from the square for hurling gin bottles out of her window. Princess Anne spent several highly publicised months living there with her new husband.

Conservative MP Iain Mills died of alcohol poisoning in his flat, with the result that John Major's government lost its parliamentary majority.

A string of other MPs have lived there, as well as businessmen and other powerful figures.

The Metropolitan Police recently appealed for information about alleged child abuse taking place in the square. Allegations of a paedophile ring involving senior military, law enforcement and political figures in the 1970s and 1980s are being investigated. The allegations include three murders.

Operation Midland is looking at whether abuse took place at Dolphin Square and other locations in London. The operation stems from allegations made by a man referred to as "Nick", who says he was taken by car to "parties" where he was abused, at a flat in the square.

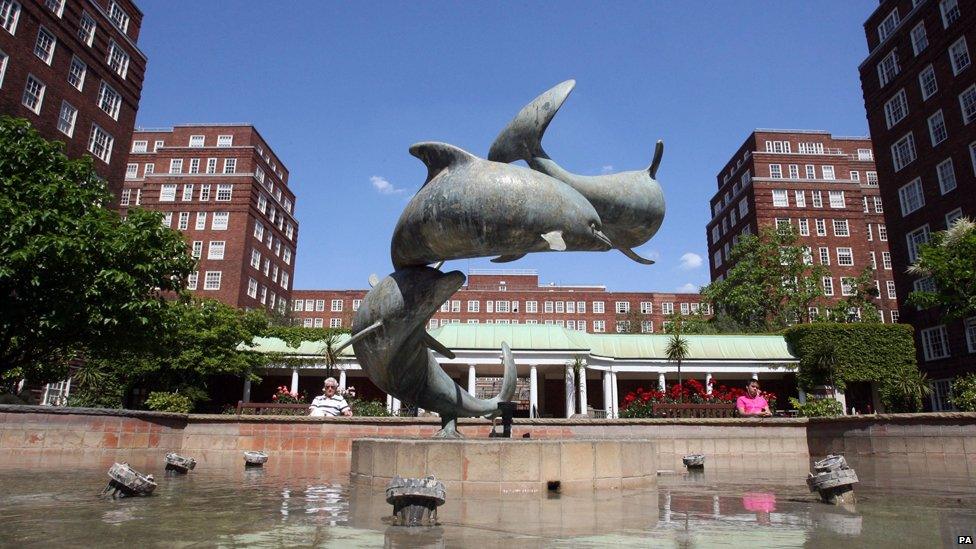

On a sunny weekday morning in August, the square bustles with activity. The 1,200 flats are set around a garden courtyard, and have views of the trees and a dolphin-shaped fountain. Residents carry shopping back from nearby supermarkets, before heading down to the private swimming pool, or setting off for the 20-minute walk to the House of Commons.

At one point more than 100 MPs and Lords rented flats in the square, with William Hague, Sir Menzies Campbell, former Liberal leader David Steel and Prime Minister Harold Wilson just some of the politicians who have used the square as their London base.

This very British address was the dream of American investors pioneering a new, socially inclusive style of living. The company behind the block insisted that it was enabling "waterside residence at Westminster for persons of very moderate income".

"Dolphin Square is rather a unique place," explains Dr Terry Gourvish, visiting fellow at the London School of Economics and author of the official history of Dolphin Square. "When it was built it was the largest block of flats in Europe. It wasn't just a place for the rich - it was a kind of experiment to allow middle and lower class people to rent in central London."

In 1937 when the square opened, the waiting list prioritised professionals based in the borough. But the residents included taxi drivers, junior clerks, West End performers, household-name comedians, military personnel, and those working anti-social hours.

Oswald Mosley was arrested in his Dolphin Square flat and taken to Holloway Prison

Aristocrat Oswald Mosley and his wife, the Mitford sister Lady Diana Mosley, were among the first to move in. "There was a healthy mix of social classes," Gourvish says. "And the square was particularly attractive to women living alone, which in 1937 was still unusual." Each section of flats had its own porter, a service that continued until 2005.

Gisela Stuart, MP for Birmingham's Bartley Green, Edgbaston, Harborne and Quinton seat, moved into Dolphin Square in 1997. To qualify for a flat, the German-born politician had to prove that this would be her second home and that she would be working as a professional in the city.

"All I needed," she explains, "was a bed and a shower. I wanted somewhere within a reasonable distance from Parliament. When I first started as an MP we still had all-night sittings."

Stuart was one of many new Labour MPs who moved into the square following the 1997 General Election, after word got around that defeated Conservative MPs were giving up their tenancies. "I remember seeing William Hague in the lift," Stuart says, "and joking with him that, never mind a General Election, you could bring down the government just by poisoning the water supply at Dolphin Square!"

By 2005, the number of MPs living in the square had dropped to 45, which is only a tiny fraction of the number of residents, which Gourvish estimates to be up to 4,000.

Jan Prebble has lived in Dolphin Square for 44 years. A former Daily Mail journalist, the 87-year-old finds it frustrating that the square has achieved notoriety. "It's a wonderful place in which to live," she says. "There is an active tenant's association, which puts on plays like Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew in the gardens. Those less fortunate in the square are well looked after. There is a Christmas lunch priced at whatever the tenant can afford."

This history of social inclusion dates back to the 1930s when Dolphin Square was built, decades before the first council blocks appeared in Britain. At that time, apartment buildings in Britain were sufficiently unusual that some people referred to them as "French flats".

And whereas previous city housing blocks had been built for the very rich (vast Kensington apartments with seven or eight rooms apiece) or the very poor (charitable blocks like the Peabody estates that replaced Victorian slums), Dolphin Square was part of a new phenomenon.

"The design and the size - small with only one or two bedrooms - shows that these are for the professional classes," says Prof Chris Hamnett from King's College, London. "I think they always had MPs in mind. These are 'service flats'."

In the inter-war years, housing standards in central London were poor. Most people had to share bathrooms, if they had one at all. Many also shared kitchens with their neighbours. Electricity, refrigerators and other amenities were extremely rare. Adverts for the first Dolphin Square tenancies boast of "London's Largest and Best Equipped flats".

The block cost a hefty £1,500,000 to build - around £91m in today's money. "These flats were a real innovation at the time," Hamnett explains. "They represented cutting-edge cleanliness and modernity. For the richer residents, a Dolphin Square flat could be a pied a terre to live in during the week, before going back to their country places at the weekend." No wonder that Agatha Christie's finicky detective Hercule Poirot inhabits a 1930s mansion flat.

Dolphin Square has its own strange connection with the world of detection. The block is conveniently located near to MI5. In the 1930s and 40s, English spymaster Maxwell Knight based himself in Dolphin Square. Knight - who is believed to be the inspiration for Ian Fleming's M - recruited a number of spies, and infiltrated communist and fascist groups.

But in the early years of WW2, Knight's job included spying on his neighbour, the fascist leader Oswald Mosley, who lived only a few doors down. In 1940, Knight had Mosley arrested and taken straight from Dolphin Square to Holloway Prison.

Dr Stephen Dorrill from the University of Huddersfield, an expert on the British intelligence services, calls it "a bizarre relationship". "Presumably they saw each other regularly in the lifts and corridors," he says. "When they met after the war, they got on quite well."

British civil servant and Soviet spy John Vassall shortly after his release from prison in 1972

In 1962 the naming of Admiralty clerk John Vassall as a Soviet spy became one of the first modern tabloid scandals. Newspapers gleefully printed descriptions of Vassall's Dolphin Square flat - the low-paid clerk's lush carpets and expensive antique furniture were used as evidence in court that he had been receiving money from the Soviet Union in exchange for Admiralty secrets.

"When Vassall was finally arrested," Dorrill says, "there was a big media expose. Journalists staked out Dolphin House, trying to work out who Vassall was seeing." The press believed that Vassall had been involved in a circle of illegal homosexual activity, including meetings with prominent Conservative politicians. "In the media's eyes, Dolphin Square had become a sort of 'den of iniquity'. It was a big embarrassment for MI5. We now know that many of the published pieces were simply made up."

By the time the model and showgirl Christine Keeler moved to the square, "it was becoming a bit of a louche place," Dorrill explains. Part of the original appeal of the 1930s "service flats" had been that they allowed residents to get by without servants.

Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies, both at the heart of the Profumo scandal, lived in Dolphin Square

In the 1960s this meant that a number of wealthy businessmen, politicians and figures from the arts industry were living alone in the square. There were also several prostitutes living there, Dorrill suggests.

Chris Hamnett sees a different change taking place in London's 1930s housing blocks. "The price of the flats in these blocks has soared astronomically. Many of the flats in Kensington are now commanding prices of £2m, £3m, even £4m." The "service flats" designed for the professional middle-class are now occupied by the rich.

At Dolphin Square, successive owners have sought to subsidise rents using money brought in from the Square's hotel and spa, and there are rumours that MPs pay a reduced rate.

The towering redbrick building may no longer have taxi drivers living alongside film stars as in the early years, but one look at the variety of cars parked outside shows that Dolphin Square has not become a base for the super-rich.

"The MPs are very friendly," says Jan Prebble. "They have arranged tours around the House of Commons for us. We have far more younger people than we had before. It is a very good place to live if you are on your own. The changing population makes it harder to foster a sense of community… but there still is one."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.