Why do wrestlers so often die young?

- Published

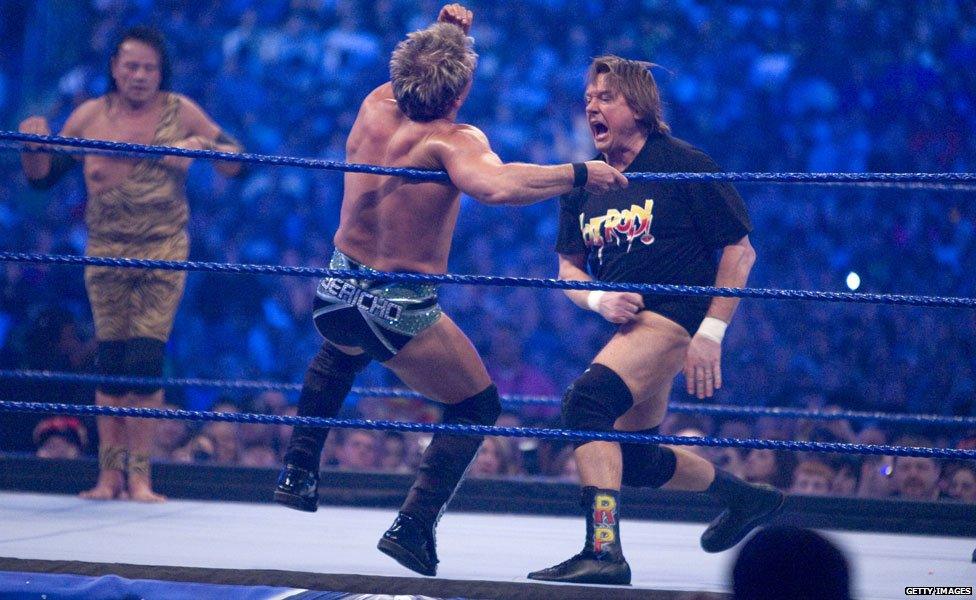

Rowdy Roddy Piper (right) in action with Chris Jericho (centre) in 2009

Mr Perfect, The Ultimate Warrior and "Rowdy" Roddy Piper may sound like names from a comic book, but the cognoscenti will recognise them as former superstars of the world of professional wrestling. All of them also died unexpectedly and at a relatively young age.

Mr Perfect died in 2003 of acute cocaine intoxication at the age of 44. The Ultimate Warrior died last year of a heart attack, aged 54. Most recent to go was "Rowdy" Roddy Piper who died suddenly on 31 July of a heart attack. He was 61.

So do former wrestlers die younger than athletes who take part in other sports?

"Yes the statistical evidence is quite strong when we look at the mortality rate for wrestlers compared to other sports and the general population," says John Moriarty of Manchester University.

Researchers like Moriarty face some difficulties getting hold of data, as no official body collects statistics about the deaths of those who have spent a career in the ring.

His approach has been to aggregate the findings of others who have studied the problem.

He points to research by academics at the University of Eastern Michigan, external who studied a group of 557 former wrestlers.

Of the 62 wrestlers in this group who died between 1985 and 2011, 49 died before the age of 50. Furthermore, 24 of the 49 died before the age of 40, and two even died before the age of 30.

Mortality rates for wrestlers aged between 45 and 54 were 2.9 times greater than the rate for men in the wider US population, the study found.

Cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death.

But how does this compare with other American sports?

In 2014 Benjamin Morris investigated this for the statistical blog FiveThirtyEight, external, looking at a group of wrestlers whose careers had ended in 1998 or earlier.

He found that 20% of those who in 2010 would have been aged between 50 and 55 had died, compared with just 4% of former American footballers of a similar age.

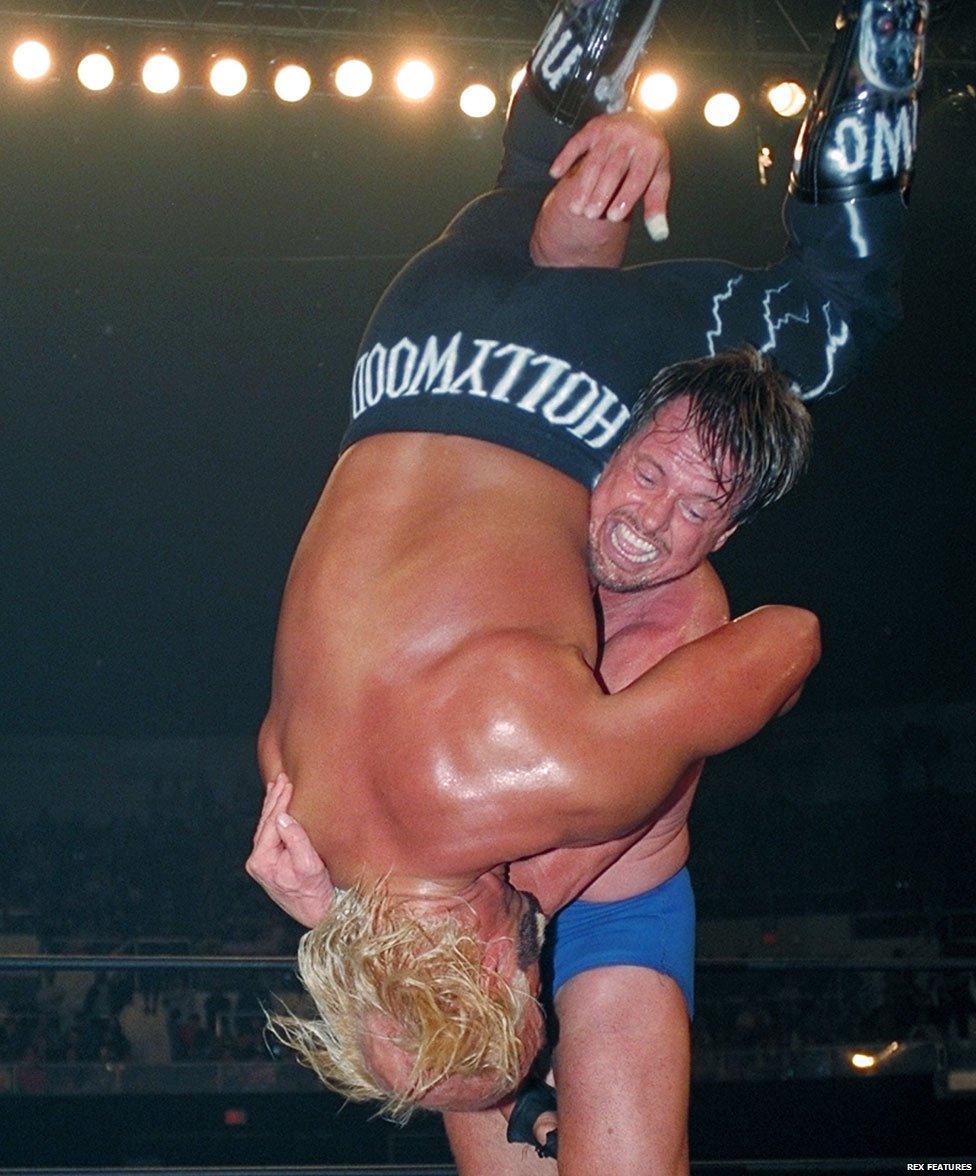

Rowdy Roddy Piper prepares to throw Hulk Hogan to the ground

Why might this be?

Both activities involve their competitors exposing themselves to physical harm, and the training regimes for both wrestling and American football are punishing.

But New York-based wrestling journalist Eric Cohen points to two important differences.

"There is no off season in pro-wrestling. American footballers play, what, 16 a games a season? And then get half a year off. Wrestlers can be in the ring five to six times a week," he says.

The other difference concerns the activities outside the ring and off the field.

"Wrestlers who competed in the 1970s and 80s were also living and partying like rock stars," Cohen says. "In the past the business has had a lot of issues with its stars abusing steroids and recreational drugs."

Piper admitted taking steroids and cocaine, and drinking heavily while competing as a wrestler.

The WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment Inc.) accepts that the culture of some of its former employees contributed to the problems they experienced in later life.

"Unfortunately, some past performers were part of a generation of wrestlers who made unhealthy and poor personal lifestyle choices, which in some cases continued beyond their years in the ring," a spokesman said in a statement.

"Today's athletes take great pride and personal responsibility for their overall health and well-being.

"Notwithstanding, WWE talent are subject to random drug testing and expected to live healthy lifestyles, reinforced through our Talent Wellness Program, which was instituted in 2006."

Cohen believes things are broadly are getting better.

"Thankfully we don't have nearly as many wrestlers in their 20s or 30s dying any more," he says.

"But as crazy as this may sound there was an incident in Mexico recently where a wrestler died in the ring, external."

The hope among wrestling fans is that today's crop of superstars will live longer than their predecessors.

But the deaths of Roddy Piper and others serve as dark reminders of the journey that professional wrestling has been on.

More or Less is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.