The Japanese women who married the enemy

- Published

American GIs were told not to fraternise with Japanese women, but they did

Seventy years ago many Japanese people in occupied Tokyo after World War Two saw US troops as the enemy. But tens of thousands of young Japanese women married GIs nonetheless - and then faced a big struggle to find their place in the US.

For 21-year-old Hiroko Tolbert, meeting her husband's parents for the first time after she had travelled to America in 1951 was a chance to make a good impression.

She picked her favourite kimono for the train journey to upstate New York, where she had heard everyone had beautiful clothes and beautiful homes.

But rather than being impressed, the family was horrified.

"My in-laws wanted me to change. They wanted me in Western clothes. So did my husband. So I went upstairs and put on something else, and the kimono was put away for many years," she says.

Hiroko enjoyed wearing traditional Japanese clothes

It was the first of many lessons that American life was not what she had imagined it to be.

"I realised I was going to live on a chicken farm, with chicken coops and manure everywhere. Nobody removed their shoes in the house. In Japanese homes we didn't wear shoes, everything was very clean - I was devastated to live in these conditions," she says.

"They also gave me a new name - Susie."

Like many Japanese war brides, Hiroko had come from a fairly wealthy family, but could not see a future in a flattened Tokyo.

"Everything was crumbled as a result of the US bombing. You couldn't find streets, or stores, it was a nightmare. We were struggling for food and lodging.

"I didn't know very much about Bill, his background or family, but I took a chance when he asked me to marry him. I couldn't live there, I had to get out to survive," she says.

Hiroko's decision to marry American GI Samuel "Bill" Tolbert didn't go down well with her relatives.

Images of the devastation in Tokyo after they were bombed by the US in World War Two.

"My mother and brother were devastated I was marrying an American. My mother was the only one that came to see me when I left. I thought, 'That's it, I'm not going to see Japan again,'" she says.

Her husband's family also warned her that people would treat her differently in the US because Japan was the former enemy.

More than 110,000 Japanese-Americans on the US West Coast had been put into internment camps in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attacks in 1941 - when more than 2,400 Americans were killed in one day.

It was the largest official forced relocation in US history, prompted by the fear that members of the community might act as spies or collaborators and help the Japanese launch further attacks.

US soldier posts a Civilian Exclusion Order for Japanese-Americans

The camps were closed in 1945, but emotions still ran high in the decade that followed.

"The war had been a war without mercy, with incredible hatred and fear on both sides. The discourse was also heavily racialised - and America was a pretty racist place at that time, with a lot of prejudice against inter-race relationships," says Prof Paul Spickard, an expert in history and Asian-American studies at the University of California.

Luckily, Hiroko found the community around her new family's rural farm in the Elmira area of New York welcoming.

Some Japanese wives attended bride schools to learn the American way of life and customs.

"One of my husband's aunts told me I would find it difficult to get anyone to deliver my baby, but she was wrong. The doctor told me he was honoured to take care of me. His wife and I became good friends - she took me over to their house to see my first Christmas tree," she says.

But other Japanese war brides found it harder to fit in to segregated America.

"I remember getting on a bus in Louisiana that was divided into two sections - black and white," recalls Atsuko Craft, who moved to the US at the age of 22 in 1952.

"I didn't know where to sit, so I sat in the middle."

Like Hiroko, Atsuko had been well-educated, but thought marrying an American would provide a better life than staying in devastated post-war Tokyo.

She says her "generous" husband - whom she met through a language exchange programme - agreed to pay for further education in the US.

Atsuko (second left) married Arnold (second right) and moved to the US in 1952

But despite graduating in microbiology and getting a good job at a hospital, she says she still faced discrimination.

"I'd go to look at a home or apartment, and when they saw me, they'd say it was already taken. They thought I would lower the real estate value. It was like blockbusting to make sure blacks wouldn't move into a neighbourhood, and it was hurtful," she says.

The Japanese wives also often faced rejection from the existing Japanese-American community, according to Prof Spickard.

"They thought they were loose women, which seems not to have been the case - most of the women [in Toyko] were running cash registers, stocking shelves, or working in jobs related to the US occupation," he says.

About 30,000 to 35,000 Japanese women migrated to the US during the 1950s, according to Spickard.

At first, the US military had ordered soldiers not to fraternise with local women and blocked requests to marry.

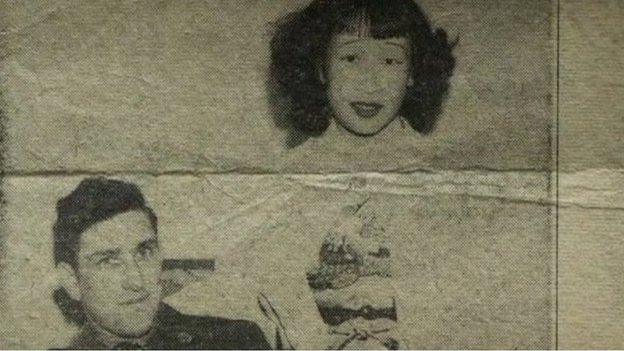

Hiroko married American GI Samuel 'Bill' Tolbert in Japan, and moved to the US in 1951

The War Brides Act of 1945 allowed American servicemen who married abroad to bring their wives home, but it took the Immigration Act of 1952 to enable Asians to come to America in large numbers.

When the women did move to the US, some attended Japanese bride schools at military bases to learn how to do things like bake cakes the American way, or walk in heels rather than the flat shoes to which they were accustomed.

But many were totally unprepared.

Generally speaking, the Japanese women that married black Americans settled more easily, Spickard says.

Some Japanese wives went to bride schools to learn how to live the American way

"Black families knew what it was like to be on the losing side. They were welcomed by the sisterhood of black women. But in small white communities in places like Ohio and Florida, their isolation was often extreme."

Atsuko, now 85, says she noticed a big difference between life in Louisiana and Maryland, near Washington DC, where she raised her two children and still lives with her husband.

And she says times have changed, and she does not experience any prejudice now.

"America is more worldly and sophisticated. I feel like a Japanese American, and I'm happy with that," she says.

Two Japanese war brides, who married US serviceman after the end of World War Two, recall the struggle to find their place in the US.

Hiroko agrees that things are different. But the 84-year-old, who divorced Samuel in 1989 and has since remarried, thinks she has changed as much as America.

"I learned to be less strict with my four children - the Japanese are disciplined and schooling is very important, it was always study, study, study. I saved money and became a successful store owner. I finally have a nice life, a beautiful home.

"I have chosen the right direction for my life - I am very much an American," she says.

But there is no Susie any more. Only Hiroko.

The full documentary Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight will air on BBC World News this weekend. Click to see the schedule.

- Published18 February 2012