Risking death at sea to escape boredom

- Published

Many people trying to start a new life in Europe want to escape war or extreme poverty, but large numbers of young Algerians are willing to risk death crossing the Mediterranean because they are bored and fed up with the lack of opportunities at home.

I crawl under a wire and nearly trip on a sleeping dog. "This way, quick!" hisses Rachid. It is pitch black so I gingerly follow the greenish glow from his mobile phone up four flights of stairs in a half-built apartment block.

We're up here because Rachid prefers to speak away from the prying eyes of the police or the twitching ears of informers. The warm wind is sweeping across from the sea. We are overlooking Sidi Salem, a rundown suburb of the Algerian port of Annaba. To our left a former French colonial army barracks has been turned into a shanty town.

"Even though I'm free, my life here is like a prison," Rachid says. "As soon as I get a call about a boat, I'll be off again to try to reach Sardinia."

Rachid is a harraga. The word means "path burner" in Arabic, a runaway who flees his or her country for a better life elsewhere. It also describes the practice of setting fire to identity papers to avoid being traced and repatriated.

Over the past decade, Sidi Salem has become a famous launch pad for illegal migrants. The Italian island of Sardinia can be reached in just 12 hours with the right weather conditions.

The harragas often use boats like these to try to get to Sardinia

Under cover of darkness, the migrants set out across the open sea, usually 10 or 12 to a boat, with jerrycans of petrol, food, blankets, an outboard motor and a GPS tracking device.

In 2009 the Algerian government made clandestine emigration a crime, punishable by fines and two to six months in prison. Equipped with new boats and helicopters, the coastguard has also stepped up night-time patrols along the country's 1,200km shoreline.

The Algerian Ministry of Religious Affairs issued a Fatwa against those who try to cross the border illegally - 14,000 mosques were instructed to preach against leaving.

But the harragas keep trying to go.

Rachid has attempted to escape three times already. Twice he made it across the Mediterranean, to Sardinia. On one occasion he managed to stay away for eight months and got into France, where he worked in a halal butcher's shop, before being caught by French police and sent home.

The second time he was sent back from Italy after 55 days. "The carabinieri told us that our President Bouteflika had paid 4,500 euros (£3,175) for each of us to be returned and put us on a plane home," says Rachid. "I felt so depressed."

He admits his situation is far from desperate. He has a job, albeit a low paid one, as a security guard and a roof over his head. He does not fear for his life on a daily basis as many Algerians did during the brutal civil war of the 1990s, the period known as "the black decade".

Find out more

The Harragas of Algeria is broadcast on Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4 at 11:00 on Thursday 20 August. It's also on Assignment on BBC World Service on the same day or you can catch up later online.

Since then Africa's biggest country has been largely peaceful. Thanks to vast reserves of oil and gas, there are plenty of imported goods in the shops. Healthcare and education are free for the country's 35 million citizens.

Young people make up more than two thirds of the population but the ruling elite consists mainly of men over the age of 70 - the ailing President, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, is in now his fourth term and many feel there is no prospect for change.

Rachid, aged 33, feels life is passing him by. "What kind of future can I have here in Algeria," he says bitterly. "There's nothing for me here."

On his last attempt to get to Europe he hid inside a cargo ship in the port of Annaba but was spotted and promptly arrested. He was fortunate. The prosecutor came from his neighbourhood and released him.

But in practice few would be migrants spend long behind bars, says Kourceila Zerguine, a lawyer in Annaba.

"Our prisons can't accommodate all the hundreds of harragas who are arrested each year," he says. "This law was imposed by the authorities under pressure from Europe. Algeria has become a guard dog for 'Fortress Europe'."

There are no official figures to show how many harragas try to leave - and many of them never reach the promised land.

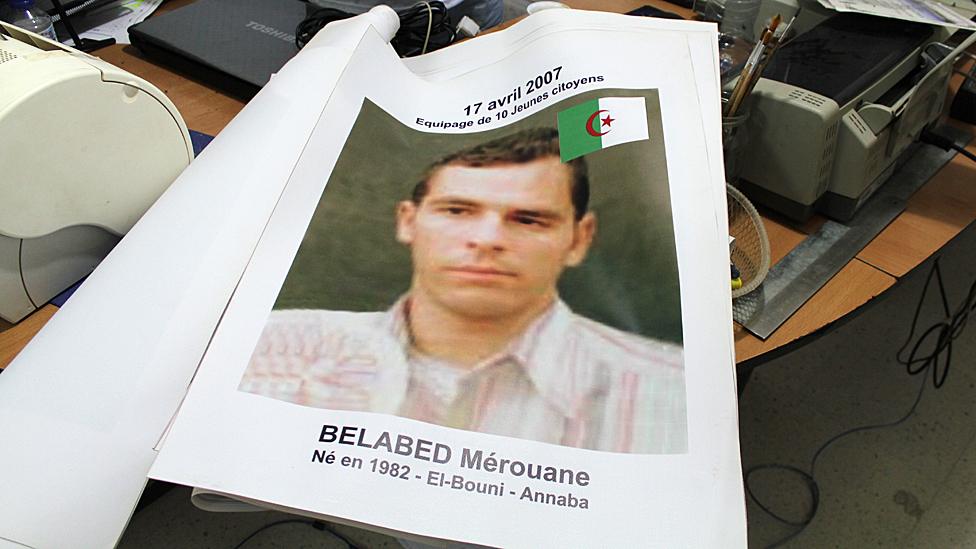

Twenty-six-year-old Merouane Belabed disappeared one April night in 2007.

He worked in his father's graphic design company. The family has a comfortable home but Merouane wanted to visit his cousins in Europe. He applied for a visa five times but was always turned down.

The night before he left he told his father, Kamel, that he was going to spend a few days in Tunisia on the beach with friends.

"He said, 'Don't worry Dad, I'm not asking for money or to borrow the car and I'll be back within 48 hours - three days at the most.' "

But the family never heard from him again. He joined a long list of Algerians missing at sea which includes doctors, engineers and even the grandson of the country's former president, Chadli Bendjedid.

The harragas have become something of a national obsession in the Algerian media, cinema and popular music.

Azzedine Nebil, better known as Azzou - one of Algeria's leading hip hop artists - has campaigned against clandestine crossings. His song Harraga tells the story of a journey to Sardinia which nearly ends in tragedy.

The lyrics describe towering waves, a boat full of water and a group of terrified young men "looking death in the face". They are rescued in the nick of time but not all harragas are so lucky.

"When I perform this song at concerts, so many people are in tears," says Azzou. "I have a friend, a boy I grew up with, who disappeared at sea, presumed drowned but they never found his body.

"What is the point of making it to Paris if you are going to live a miserable hand-to-mouth existence selling contraband cigarettes on the street? You can create your own dream here, in your own village. You just need to think differently."

But despite all the subsidies for cooking oil, sugar, petrol and text books, hope is a commodity in short supply in Algeria. An Islamist opposition leader once described Algerian youth as having a choice "between death at sea and a slow, gradual death at home" given the lack of opportunities in a stagnant economy dominated by nepotism and corruption.

President Bouteflika has blamed satellite TV for spreading propaganda about "a pseudo overseas prosperity". And the internet may also have helped to give Algerian youth a chronic, collective case of FOMO - Fear of Missing Out as the diaspora relay tales of social, religious and sexual freedoms and a lively nightlife as well as better job prospects abroad.

The government has urged young people to stay put to help build their own nation. Since the uprising in neighbouring Tunisia, which began in 2010, the Algerian authorities have extended youth employment schemes and given young people interest free loans to set up their own businesses.

Mourad Zemali who heads ANSEJ, the agency which funds entrepreneurs, says so far 340,000 projects have been financed which have created more than 800,000 jobs. At a time of plummeting oil prices, he tells me the state is well aware of the need to diversify the economy into areas such as digital technology and tourism.

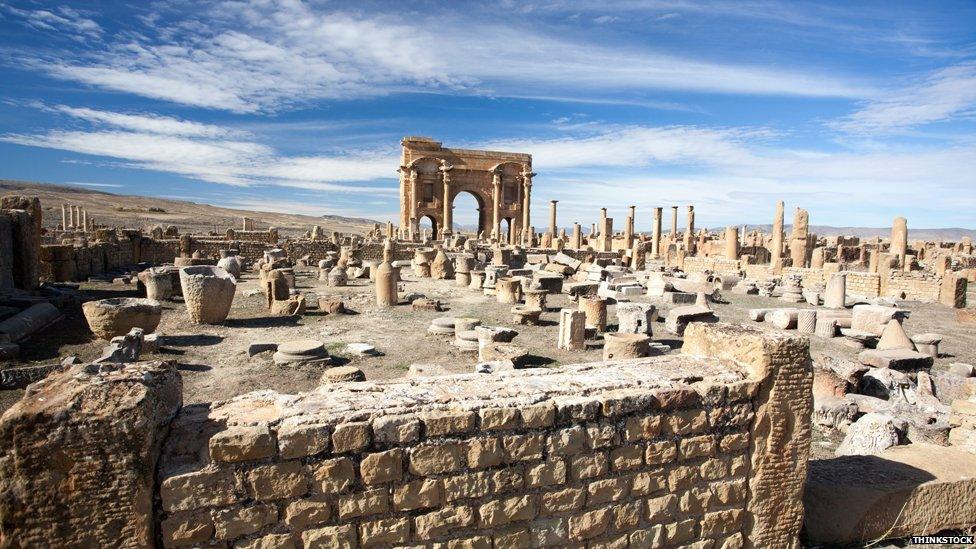

The Roman ruins of Timgad in north-east Algeria

Despite stunning scenery and a wealth of cultural treasures - including well preserved Roman cities - incidents such as the murder of a French tourist last year and the hostage crisis following an attack on a gas plant in 2013 have discouraged visitors.

And in a country where the state sector provides about 60% of jobs the service culture is sluggish, possibly a legacy of Soviet style centralised economy in the decades after Algerian independence.

"We are helping to provoke changes in mentality," says Mr Zemali. "As well as financial help, we are trying to give young people values, get them to take responsibility for themselves. So we're creating a new generation which takes initiative, which is dynamic."

He admits that some of the companies funded by ANSEJ have gone bust but argues that bankruptcy for some start-ups is inevitable. "The fact that they have tried to create a business employing other people in itself counts as a success," he says.

Yet some are sceptical. Yousef Othomani, who went to catering school in Switzerland, worked in London and has just opened a restaurant in Algiers, suspects the fund is yet another way to mask the lack of real change in Algeria.

Yousef Othomani's restaurant Bad Buns - he calls it "New York without a visa"

He says many young people got loans to set up car rental companies but in practice they just bought fancy new cars for their personal use.

"That is very common and the government doesn't run after you to pay back the money," he adds. "I don't think it encourages entrepreneurship - they don't ask you for a proper business plan. I see it more as a way of buying the youth. If you guys vote for us and keep us in government, this is what you get."

However Kamel Daoud, one of the country's best known writers, says it's not the economy but sheer boredom that's driving many young Algerians away.

"Our harragas don't leave the country because they are poor or jobless…. even if that's what they say," he wrote in Le Quotidien d'Oran, the daily paper from Algeria's second largest city. "They leave because here, in this country, their lives are pointless, there's no room to dream, and worst of all, there's no fun, no laughter, no kissing, and no colour."

And life in Algeria's villages is one where "the boredom is unrelenting, unbelievable, unbearable and inhuman," he said.

Young people say they are sick of being treated with contempt - and too often their response is, "Al harga wala hogra" - better to burn than be humiliated.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.