How many national anthems are plagiarised?

- Published

Several of the world's national anthems are shockingly similar to other compositions. Is this because composers pilfer other people's tunes - or does it tell us more about the difficulties of writing an original melody, asks Alex Marshall, author of a new book on the history of national anthems.

Dusan Sestic is arguably the world's unluckiest composer. Back in 1998, he found himself short of money so decided to enter the contest for a new Bosnian national anthem, one meant to help heal the country's bitter ethnic divides following its civil war. He didn't really want to win - he was more nostalgic for Yugoslavia than patriotic for the new country - so entered a gently stirring song, external that he felt good enough to come second or third, pocket some prize money and move on.

But he won, and his life changed dramatically overnight.

Fellow Serbs, some of whom opposed the very existence of Bosnia, started labelling him a traitor. Many Bosniaks and Croats were equally annoyed that an ethnic Serb had written the tune that would symbolise their country. He struggled to get work.

Ten years later, he won a second competition for words to the anthem, but ethnically motivated politicians refused to approve them. He's still owed 15,000 euros (£11,000) for that effort.

Then in 2009, as if that wasn't enough, someone made a discovery. It turned out that Dusan's anthem was remarkably similar to the music that opens National Lampoon's Animal House, external - the 1978 film about a debauched university fraternity.

Immediately some called for Dusan's anthem to be dropped and he was accused of plagiarism. A newspaper even apparently tracked down the Animal House composer's family and tried to get them to sue. Dusan had to go on TV to defend himself.

"I was hurt by the headlines," he told me earlier this year in the largely Serb city of Banja Luka.

"I didn't know the name of the movie, but I listened to it and I was really, really surprised. I thought about it, and perhaps as a young man, I'd seen the movie or heard the song and it stuck in my brain somehow, this musical code. It's definitely possible - but I cannot say this is plagiarism."

He pointed out some differences between the two melodies. "Not everyone in this country is a thief or corrupt," he added. "If I was, I would be a politician and be doing far better in life."

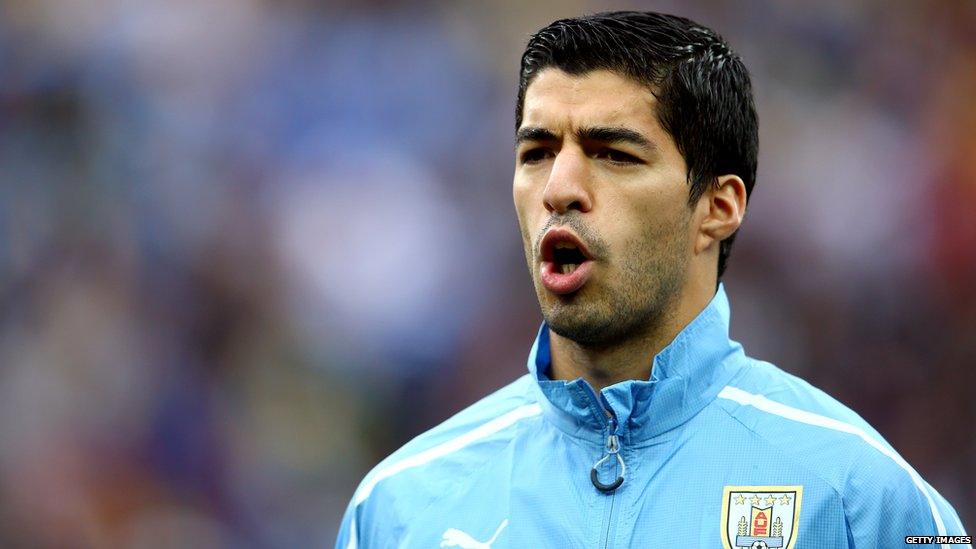

Strangely enough, Dusan's is far from the only anthem tainted by accusations of plagiarism. Take Uruguay's, external - written in 1846 by Francisco Jose Debali. It's one of the most exciting anthems there is - more like a mini-opera than anything else - but its main theme is exactly the same as a fragment of Donizetti's opera, Lucrezia Borgia.

Donizetti's opera Lucrezia Borgia: Did it provide Uruguay with its national anthem?

There is evidence Debali could have heard the opera a few years before putting ink to paper - parts of it were performed in Montevideo in 1841, and he may even have heard it in Italy before moving to the country.

The anthem and the opera share a run of nine exact notes. But Debali supporters point out it is only nine notes and they occur a quarter of the way through a two-hour opera. Perhaps it's just coincidence.

The issue wasn't raised in Debali's lifetime, so he never had to face the accusations Dusan has had to put up with.

The rambunctious introduction to Argentina's anthem, external has also been accused of similarities to a piece by Clementi, external, while Enoch Sontonga, the man behind South Africa's graceful Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika, external, is often said to have taken his melody from Aberystwyth, external, by the the Welsh composer Joseph Parry - although both of those examples seem rather far-fetched.

A mourner sings the South African national anthem after Nelson Mandela's death in 2013

It could actually be said that there is a tradition of borrowing, when it comes to national anthems. The first anthem, as we'd recognise the concept today, was Britain's God Save the King. It was a traditional song revived in 1745 during Bonnie Prince Charlie's invasion to restore the Stuart throne. It didn't take long for the invasion to be defeated, but God Save the King kept being sung for decades afterwards to the point that other monarchs started thinking they needed an anthem like it. Soon its melody was in use in Denmark, most of the German states, Russia too. It even ended up as an anthem for the Kingdom of Hawaii. People simply took the music and put different words over on top.

Eventually most of those countries decided it was important to have a melody of their own. But there is still one country outside the Commonwealth that stubbornly refuses to budge: Liechtenstein. If you go there, you can hear people happily sing Oben am Jungen Rhein, external (Over the young Rhine) without a moment's thought for the fact that a British person present could join in, with different words.

All Liechtensteiners know, of course, that they share Britain's tune, but they actually seem rather proud of it. "It's been so popular here, there's never been an idea to change it," the country's ruling prince, Hans-Adam II, told me. "And we're in good company with the UK. Great company I would say."

In a similar vein, Estonia and Finland share the same melody, external for their anthem - which meant Estonians could still hear their anthem under Soviet rule by tuning into Finnish radio stations. The tune, written by German composer Fredrik Pacius, is said by some to be based on a German drinking song.

Many anthems, meanwhile, use folk tunes for their anthems. Samuel Cohen, who composed Israel's wrenching Hatikvah, external (The Hope) in 1888 said he took its melody from a traditional Romanian tune, external - although some claim he actually stole it from a piece by the Czech composer Bedrich Smetana, external. (Either way, the melody was first heard in 17th Century Italy.)

Shared anthem tunes

The UK and Lichtenstein

Estonia and Finland

South Africa, Zambia and Tanzania

Similarly, South Korea and the Maldives once used the tune of Auld Lang Syne for their anthems. South Korea inherited it from Scottish missionaries. The poet behind the Maldives' anthem, for his part, chose the music after hearing it chiming out of an uncle's novelty clock.

Even the Star-Spangled Banner isn't original, sung to the tune of an old British drinking society song, To Anacreon in Heaven. When politicians were debating whether to adopt it as the country's official anthem, many objected, arguing that a unique American melody was needed - and definitely not one people used to get drunk to.

South Korean schoolchildren stand to attention during their national anthem

What does all this borrowing show? That anthems are exempt from the laws of plagiarism? That people care so little about these songs they don't notice they're unoriginal?

Perhaps, but what I actually think it shows is just how difficult it is to be original. If you write an anthem today, you need to come up with a melody so simple it can be whistled in the street and bellowed at football matches - but one that's also dignified and stirring. The chances of doing that while composing something that's not reminiscent of an existing composition are remarkably slim.

In Bosnia, the song many would like to be the country's anthem instead of Dusan's is Jedna si Jedina, external (You Are the One and Only) - some Bosniaks even sing it over Dusan's anthem at sports events. Dino Merlin, one of the country's most popular musicians, wrote the song during the siege of Sarajevo. Only the words, though. The music he took straight from a folk song.

Alex Marshall's book, Republic or Death! Travels in Search of National Anthems is published on 27 August. He discusses Bosnia's anthem, external, God Save the Queen, external and the anthems of South America, external on his blog.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.