Viewpoint: Why don't people talk about their dreams?

- Published

Once books about dreams were massively popular. Now few people look for answers in their slumbers, writes Shane McCorristine.

I had the same dream again a few weeks ago.

In the dream I awake in the middle of the night and a sense of panic overcomes me. "Have I remembered to lock the front door?" I am driven by an unstoppable impulse to leave my bed and walk slowly down the pitch-black stairs towards the door.

The dread is unbearable because I already know what will happen. I touch the handle and begin to sense the utter darkness outside. I wonder: "Why am I doing this? There are things out there that will come in!"

I push down the handle, because I need to check if the door is locked, and it opens. Waves of fear wash over me and my heartbeat races because at that very moment a giant, elongated arm reaches in, from the night, and starts to claw at me. I push back the door as hard as I can, but the pressure is too great, and I know in any case that it is too late. Whatever it is that is outside will get into my home, and, unbelievably, it is I who have let it in.

I have always been fascinated by dreams, by the images, visions, and feelings that seem to autonomously pass through our minds while we sleep.

The average person spends about six years of their life dreaming in so-called "rapid eye movement" sleep, and this doesn't even take account of all the non-REM dreams and dreamlike states we experience.

Dreams have had such emotional force in my nocturnal life that I have often wondered where they come from, what function they serve, and what they really mean. I even kept a dream journal as a teenager and mentioned particularly chilling nightmares to friends and family. In this I was participating in a ritual that has taken place in each and every human society from time immemorial.

Nightly dreaming is a feature of the normatively-functioning brain - it is therefore part of our biological inheritance, and we probably adapted it to prepare ourselves for moments of danger. While other mammals also dream, talking, writing, and reflecting on dreams are practices that define us as a highly social species. We need to talk about dreams because dreams make us who we are.

From the dream-books of ancient Greece to Sigmund Freud's couch in the 20th Century, the history of dreams is the history of communication, of people sharing their dreams with others, writing them down, painting them, or indeed, repressing and ignoring them.

For most of our evolutionary history dreams have been seen as messages sent from beings outside us to offer advice, guidance, or warnings about particular futures and it is hard to overestimate the role that dream-revelations have played in the development of the world's major myths, religions, literatures, and scientific discoveries.

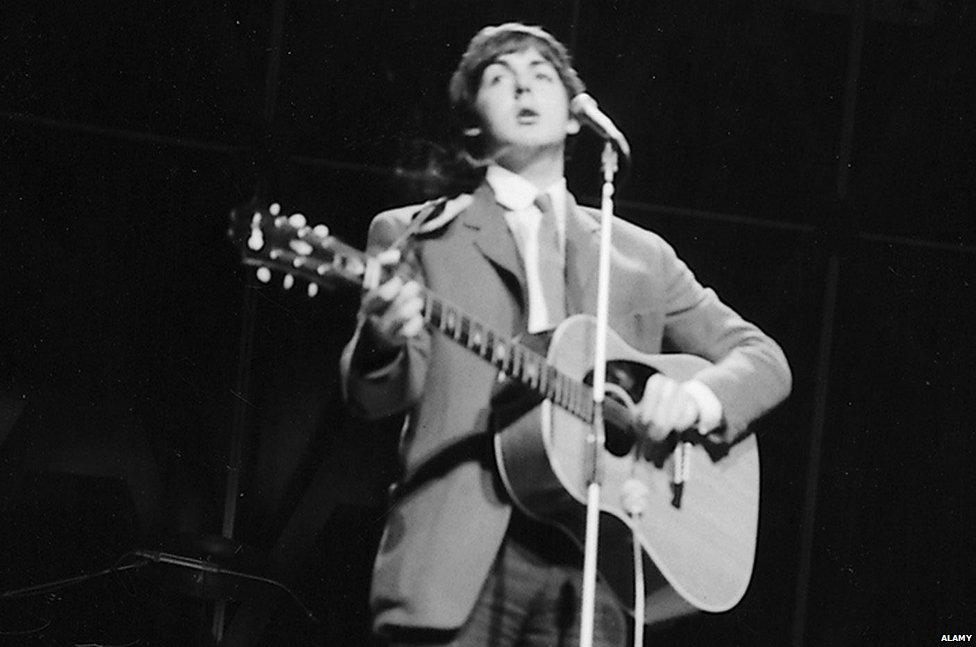

Paul McCartney has spoken about how the melody for Yesterday came to him in a dream

The iconic dreams we are all familiar with, from Jacob's dream at Bethel in the Bible to Paul McCartney's dream-composition of Yesterday in 1964, have one thing in common - they were shared with others, just as I shared my dream with you. But things have suddenly changed.

Now that neurologists and psychologists see dreams as internal creations of the brain and mind, rather than external messages directed to the soul, people, especially in Western, affluent societies, no longer grant dreams the authority their ancestors once did. I sense that the sharing of dreams is declining because, on the one hand, sleep science explains them away as bizarre narratives caused by brain activities, while psychoanalysts see them as disguising repressed sexual content. Many people therefore either think nothing of them, or are embarrassed by them.

I want to suggest that in not talking about our dreams anymore we are at risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. As dream-interpretation is outsourced to specialist experts, we are losing a vernacular that humans have always spoken together, regardless of rank, race, creed, or gender. This collapse in the democratic dream-archive may well have implications for the historians of the future, who will have little access to the most amazing stories of our innermost fears and desires.

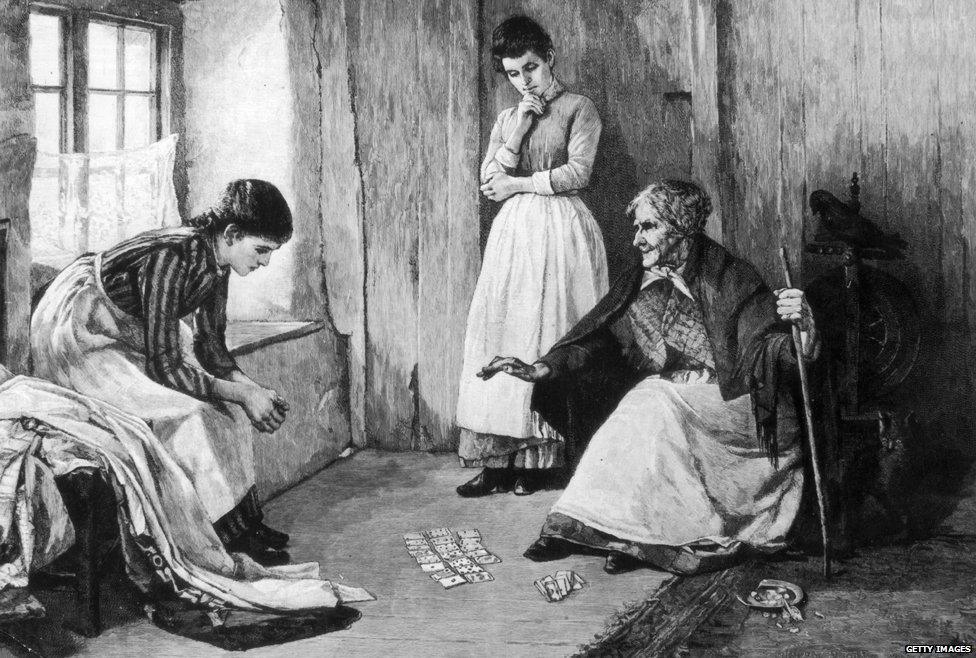

'Consulting the Wise Woman' - engraving by Henry M Rheam, 1892

This shift is all the more odd because it was only 100 years ago that ordinary people in Britain still discussed their dreams with friends, family, and co-workers with little sense of embarrassment.

Dream-books and popular almanacs were bestsellers in 19th Century Britain, guiding people's understanding of their dream content and shaping their everyday behaviours.

Typically these guides operated according to the logic of reversal - so for example, a dream about a marriage meant that a death would soon occur, while a dream about vomiting blood was a sure sign that one would come into money. Fortune tellers, talismans, and dream-interpreters were as much a feature of industrial cities, like Birmingham, Manchester, and London as were factories and department stores.

In middle-class culture meanwhile, the Society for Psychical Research, founded in Cambridge in 1882, collected hundreds of detailed dreams from people all over the Empire. The psychical researchers were particularly interested in dreams that were coincident with the death of a loved one. Indeed, they received so many accounts of death-dreams that they had to devise new statistical methods to deal with the data and invented the concept of telepathy in the process.

Because the public was so willing to share their dreams and visions, the society was able to conduct a groundbreaking census in the 1890s which estimated that around 10% of the population had experienced a hallucination.

As a historian working in this field, I am incredibly lucky that these dreams and visions were all recorded, shared, and preserved, because any culture's attitude to dreams is almost as interesting as the dreams themselves.

In my new research project I have turned dream-collector and found over 300 cases where people all over Britain were willing to tell the police, coroners, or journalists about strange dreams they had. For instance, in Hartlepool in 1866 a Mrs Clinton dreamt that a local labourer had stolen two watches worth £15 - she told her daughter and then the police, who tracked down the thief to Manchester.

In Wigan in 1878, an inquest heard that a mother warned her son not to go into work on the railways as she dreamed he would be killed - he ignored this advice and died after being knocked down by a train. In 1896, a miner named William Walters spent the day in the pub after a dream which correctly informed him there would be a fatal accident at the colliery where he worked in south Wales.

In almost all of the cases I've found, the dreams seemed to provide a warning about the sudden death of oneself or a loved one, or informed the dreamer about the location of stolen property or the body of a missing person.

Not only were people sharing these pragmatic dreams, but coroners were recording them without embarrassment at inquests involving suicides, mining disasters, car crashes, murders, and shipwrecks. This archive is incredibly valuable because it provides evidence that, for working-class people, dreams were part of a strategy of pragmatic risk management.

For risky occupations and lifestyles such as mining and deep-sea fishing, dreaming of death appears to have been one way of controlling the future and managing loss, especially among women who depended on male wage-earners. These hundreds of dreams then, both their content and their sharing, give us an insight into how people managed to think and talk about an uncertain future of loss, death, or widowhood.

Dreams mattered to people, and far from being flim-flam, they related to lives and livelihoods. These seemingly prophetic dreams continue to be reported and discussed at coroners' courts up until the 1920s, when they gradually stopped. So why was this and why do we no longer tell the police our dreams?

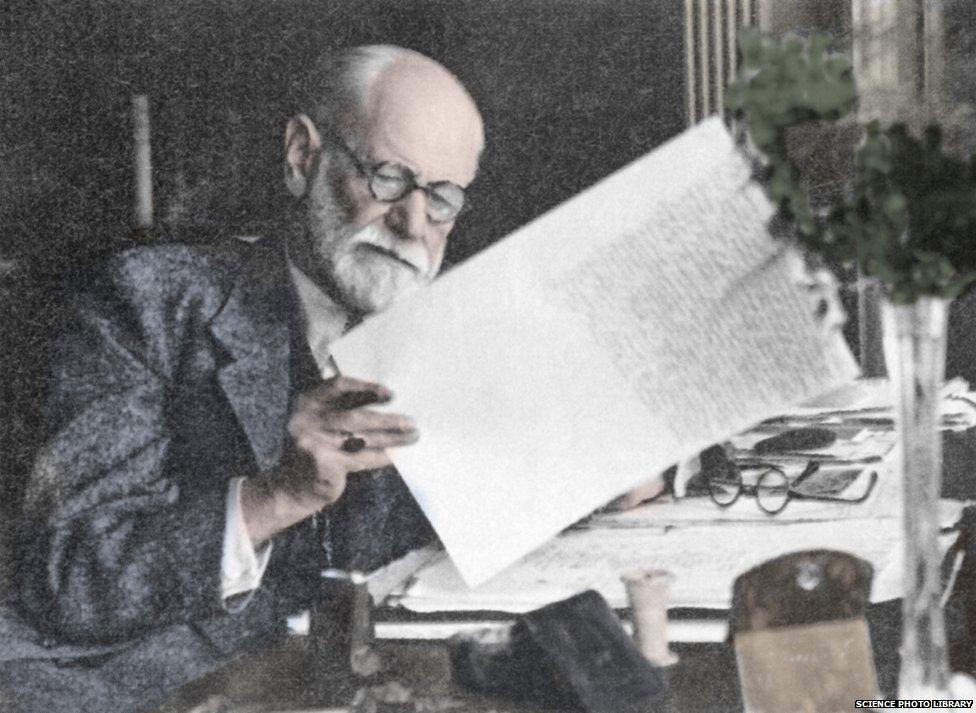

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud asked patients to share their dreams as part of their therapy

I think people largely ceded their sovereignty over dreams to the emerging disciplines of neurology and psychology. In line with the spread of secularism and a growing intolerance for so-called "popular superstitions", dreams as external messages no longer made commonsense by the mid-20th Century.

The ubiquity of the Freudian model of dreams as repressed wish-fulfilments - which looked to the past of the individual, and not the future - played a key role in making people think that dreams were internal, private matters, and not the kind of thing you discussed with others.

People still had dreams that they considered prophetic, but it was no longer considered appropriate to share them with public authorities because the dream vernacular was no longer spoken at large. Indeed, in a shocking case from Chicago in 1980, a Bible student named Steven Linscott was wrongfully convicted of the rape and murder of a neighbour after he told police that he had had a dream about a similar murder on the very same night. State prosecutors took this dream to be a confession and Linscott served three years of a 40-year sentence before a retrial and eventual exoneration.

The other reason why people don't talk about dreams so much any more relates to the incremental loss of the night and darkness.

As "9 to 5" and "24/7" lifestyles developed in the 20th Century, our nocturnal environments became almost permanently illuminated by artificial light, indoors and outdoors.

Work patterns suddenly changed as night-shifts became an essential component of capitalist modernity and this has had dramatic effects on our biological clocks and the clocks of animals and insects around us.

Where in the past dusk and dawn signalled the time to sleep and the time to wake, it seems that now the light and the half-light of the day has conquered the night. Most of us are getting by with a sleep deficit and sleep deprivation is already a major public health issue.

The economic transformation of Britain has led to an astonishing loss of the night sky through light pollution, just as it has led to the loss of a whole range of social customs associated with the dark, not least storytelling. We now rely on radio, television, and cinema to tell us stories at night, and indeed several of the great directors of the 20th Century have consciously thought of themselves as dream-weavers.

And so at midnight, when we finally put down our glowing phones and tablets and try to fall into a caffeine-haunted, alarm-clock monitored sleep, dreaming and discussing our dreams is probably the last thing on our minds.

The blue light emitted from smartphones and tablets has been linked to disrupted sleep

And yet, we continue to dream, from the womb until we die. Although we may not have time to remember dreams, our body always makes the time to dream them for us.

We are all lifetime citizens of the Revolutionary Republic of Dreams, and after we die, the people we knew and loved will dream about us. There are of course neurological, physiological, and evolutionary reasons for why we dream, and these come across in the classic and universal dream themes of sex, death, flying, being chased, and being unprepared for a major event.

But there is a consensus among scientists that, outside the laboratory, dreams are forms of self-expression and they are informed by our social lives. Dreams need not be thought of as solely private things disconnected from our relations with others.

I think we need to think more about dreams and become our own archivists. We can start by writing them down if we remember them, perhaps even sharing some with our loved ones, just as humans have been doing for tens of thousands of years.

People share all kinds of personal information at the watercooler these days and mindfulness is all the rage - why continue to ignore such an important life experience? As a historian I worry that unless we resist this forgetting of dreams, the archives of the future will be impoverished.

The Magazine on dreaming

"Lucid dreaming" technically refers to any occasion when the sleeper is aware they are dreaming. But it is also used to describe the idea of being able to control those dreams.

This is based on an edited transcript of BBC Radio 4's Four Thought on 2 September at 20:45 BST, or via the iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.