Witnessing Japan's surrender in China

- Published

In September 1945, China's long and bloody war with Japan finally came to an end - millions had died and thousands of foreigners were held in internment camps. As Japan surrendered, my great-uncle was sent to Shanghai to find out what had happened to British citizens trapped during World War Two.

By 1945, China had been fighting for eight years, longer than any other Allied power. It had lost perhaps 14 million people, second only to the Soviet Union.

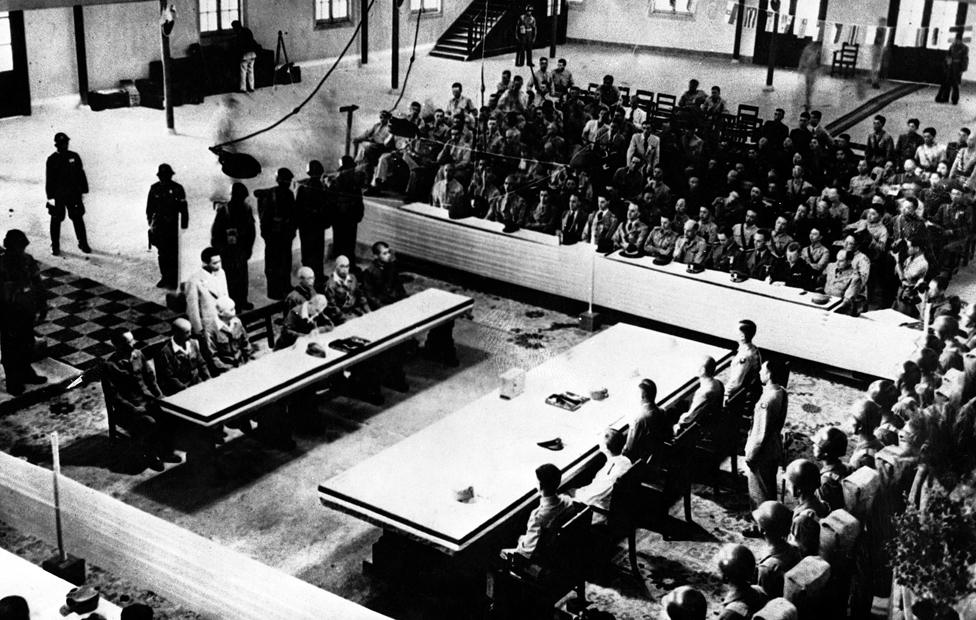

On 9 September, inside an assembly hall at the military academy in Nanjing, the Chinese Chief of Staff Ho Ying Qin waited for the arrival of Japanese general Yasutsugu Okamura. At two long tables the victors and vanquished sat facing each other. A few feet away a small group of foreigners sat watching. In the middle, in the uniform of a British major-general, sat my great-uncle, Eric Hayes.

Gen Hayes had started his career fighting in another forgotten war - the 1915 invasion of Mesopotamia. In 1919 he was sent to Siberia to fight with the Whites against the Bolsheviks. He spent two years in Bolshevik prisons, becoming fluent in Russian.

In late 1944 he was sent on another obscure mission, to be commander of British forces in China. Britain didn't really have any forces in China, but Chiang Kai-shek's nationalist regime was now an ally in the war against Japan.

In 1938, as the Japanese swept across eastern China, Chiang's nationalist regime had taken refuge in Chongqing, deep in the mountains of western China, clinging to the banks of the Yangtze River. Mao Zedong and his communist guerrilla army were far to the north in the caves of Yanan on the high Loess plateau of Shaanxi.

My great-uncle took up residence at Number 17 Guo Fu Road, a few hundred metres from Generalissimo Chiang's headquarters.

For years the people of Chongqing had been terrorised by Japanese aerial bombing. Japan wanted China out of the war and was trying to force Chiang Kai-shek to negotiate a truce.

"When the Japanese planes first arrived we had no idea about bombing," says Su Yuankui, a small, energetic-83-year old. "We went out into the streets to look at them. But then we heard the explosions and saw houses burning."

Su's family lived in an old three-storey house but soon the whole population of the city was digging tunnels to use as bomb shelters. But there were never enough of them, and in June 1941 it led to a terrible disaster.

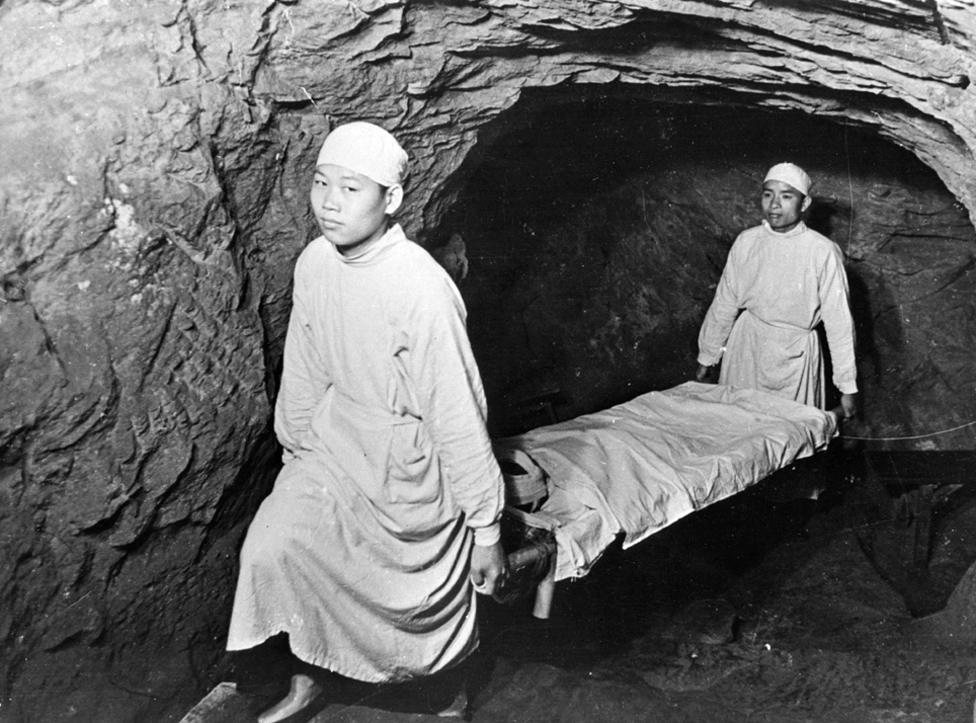

Stretcher bearers at work in the shelters below Chongqing, 1938

"Just after dinner we heard the siren and ran to the shelter," Su tells me. "People kept coming in behind us - more and more. My father said, 'It's no good, the air is getting bad, we should get out.' But people were still flooding in. People began fighting, pulling their hair and their clothes, even biting. They couldn't breathe."

Su crouched down in a corner trying to find air. He blacked out.

"The next morning there were dead people on top of me. Rescuers were pulling them off. They shook me and I woke up. They were shocked. 'Look this little one is alive!' they shouted."

Outside on the street hundreds of bodies were laid out. It's not clear exactly how many died that day, perhaps 3,000. Among them were Su Yuankui's two older sisters.

Su Yuankui in one of the underground tunnels which still exist today

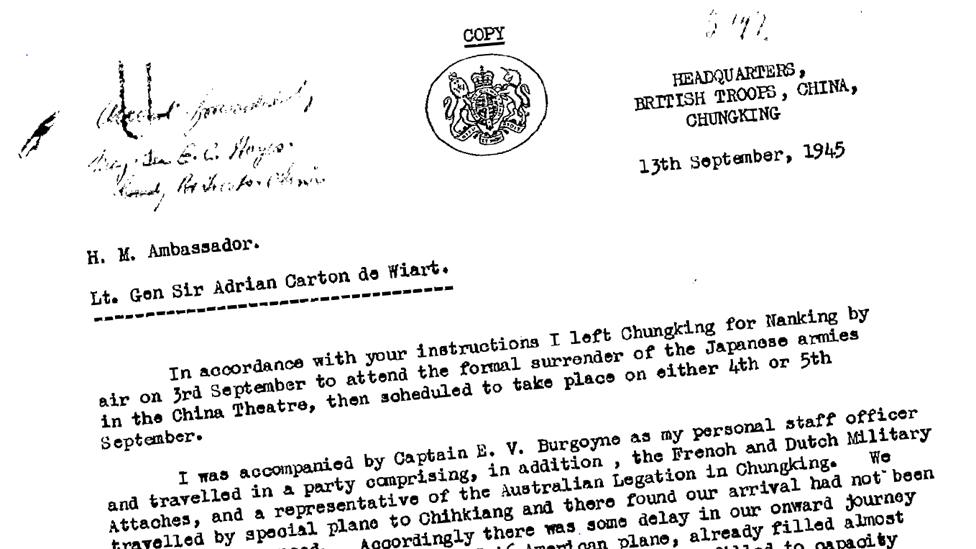

On 15 August 1945 China's long nightmare came to an end. Two weeks later, in Tokyo Bay, Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender. On the same day in Chongqing, Gen Hayes received orders to get to the Chinese capital, Nanjing, as soon as possible. He hitched a ride aboard an American C46 transport, already filled with war correspondents.

"The plane was also filled to capacity with petrol, and as a result, we waddled off the ground with some difficulty at the last moment and with further difficulty cleared the surrounding hills," he wrote.

Arriving in Nanjing on 3 September, he found what he described as a "fantastic situation".

"We found that we were only the sixth Allied plane to land at Nanking airfield, which was still entirely under Japanese protection, if not control. At that time in Nanking there were only some fifty Americans and 200-300 Chinese Commando troops, against 70,000 Japanese quartered in the city."

The Japanese empire in China had collapsed over night. It was clear to my great-uncle that the Japanese army in Nanjing was not happy with its orders.

"The Japanese army gave me the impression of being extremely tough and dangerous as indeed it had proved itself in battle," he wrote. "There is clearly no realisation of the extent of the disaster Japan has suffered. It regards itself, with some reason, as an undefeated army which, to its regret, has been ordered by the emperor to lay down its arms."

The signing of the document in Nanjing that formally ended the war in China

The surrender ceremony, scheduled for 5 September, was delayed for four days, and so Gen Hayes decided to travel on to Shanghai. His orders were to find out what had happened to the city's large British community.

There were no planes, and the train service was still completely under Japanese control. At Nanjing railway station the trains were crammed with Japanese troops. The first-class compartment was occupied by a Japanese general and his mistress, who were not about to make way for a British general.

"I appeared to be faced with one of two unpleasant alternatives, either to beat a retreat with what dignity I could muster and so lose a great deal of face, or to attempt to have a compartment cleared of Japanese and so risk an unfortunate incident," he wrote.

In the end a third option was found. The Japanese ejected a group of Chinese from another carriage.

"Let us hope the ejected Chinese were puppets!" my great-uncle wrote. Puppets was the term used for those who had collaborated with the Japanese occupation.

Even in victory the Chinese were still being humiliated by foreigners.

Once in Shanghai, Gen Hayes found that most of the British community was still living in Japanese internment camps.

One 13-year-old girl, Betty Barr, was interned with her family a the Lunghua camp, along with JG Ballard and his family (of Empire of the Sun fame). Lunghua was the largest internment camp in Shanghai with around 1,600 Britons.

Now 83, Betty still lives in Shanghai with her Chinese husband, George. Today the Lunghua camp is an elite Chinese boarding school, but many of the buildings from the 1940s are still there. As we walk around the leafy campus Betty points to where the Japanese camp commandant, Tomohiko Hayashi, had his office; the assembly hall where they would put on amateur dramatics; and the pond where they got water to flush the toilets.

For two-and-a-half years they were virtually cut off from the world, not knowing who was winning or when it might all be over.

"We had nothing except for rumours that must have come from secret radios," Betty says. "And then in May 1945 we saw American planes in the sky over here writing V - V - V in the sky for VE day… so we knew that Germany had been defeated."

A scene from the film Empire of the Sun, based on JG Ballard's time in Lunghua

Life in the camp was monotonous and the internees were hungry, but the Chinese in Shanghai were suffering much more. Betty's future husband, George, was living in a tiny attic with his mother and seven siblings. His father had been sent to work in a coal mine in Manchuria, in the north-east of the country, where he died. The children were slowly starving.

"My mother, she had to sell my younger sister to get money," he says. "That morning she brought pancakes. We were so happy! We hadn't eaten them for several months. Suddenly I saw my mother was sad and not eating. I asked her why are you not eating? She said, you are eating your younger sister's flesh!"

In Lunghua camp Betty's American mother kept a meticulous diary. On 14 August 1945 she wrote: "Allies have accepted Japanese surrender, but no confirming message coming from Japanese. Fears that Japanese army in China will fight on. People greatly depressed wondering why no news."

But a day later the mood had changed completely:

"Confirmed that the war is over. Great jubilation! Thanksgiving service at 3pm out of doors. Six flags unfurled on top of F block. Entertainment on both roofs until midnight, clear sky, bright moon. Perfect."

Betty reads from her mother's diary

But the end of the war brought more uncertainty. Shanghai was in chaos, no-one knew who was in charge. So Betty's family stayed put at Lunghua.

Finally, nearly three weeks later on 6 September, her mother wrote: "Gen Hayes British General in charge in China came here today, with some others. Went to Nanking for treaty signing. Says we repatriates will be sent to Manila to be sorted."

Residents of Shanghai celebrate the end of the war

With him, Gen Hayes brought some very unwelcome news. The allies had agreed that after the war the Shanghai International Settlement would be abolished. Nearly a century earlier the British had forced Imperial China to hand over a large chunk of Shanghai to British rule. Other countries had followed suit. Inside these so-called "concessions" foreigners had their own town councils, police forces, laws and courts.

"I found a remarkable lack of realisation of the implications of the abolition of extra-territoriality and of the fact that from now on Shanghai will be essentially a Chinese city," Gen Hayes wrote.

It was the end of an era. Many foreigners wanted to stay. But within four years they would all be gone. As Mao's communist forces swept south in the summer of 1949 the foreign community fled. For the next 30 years Europe and America turned away from China - and forgot the part it had played in the bloodiest war in history.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.