Palladio: The architect who inspired our love of columns

- Published

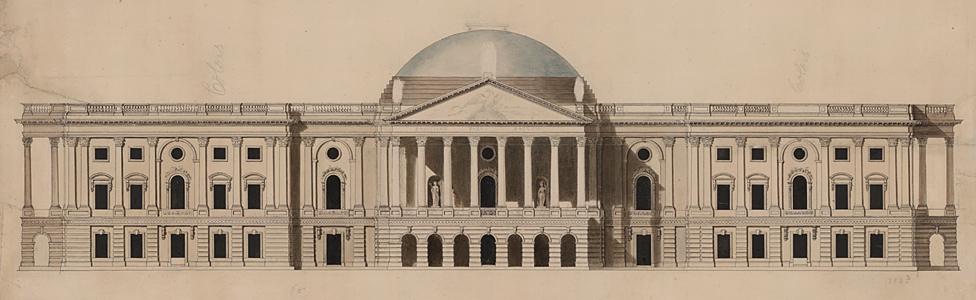

Design for US Capitol, Washington DC - by William Thornton, 1793-1800

Andrea Palladio - an Italian who lived 500 years ago - is the only architect whose style is recognised with a suffix in English. As a new exhibition opens in London, we explore the enduring popularity of "Palladianism".

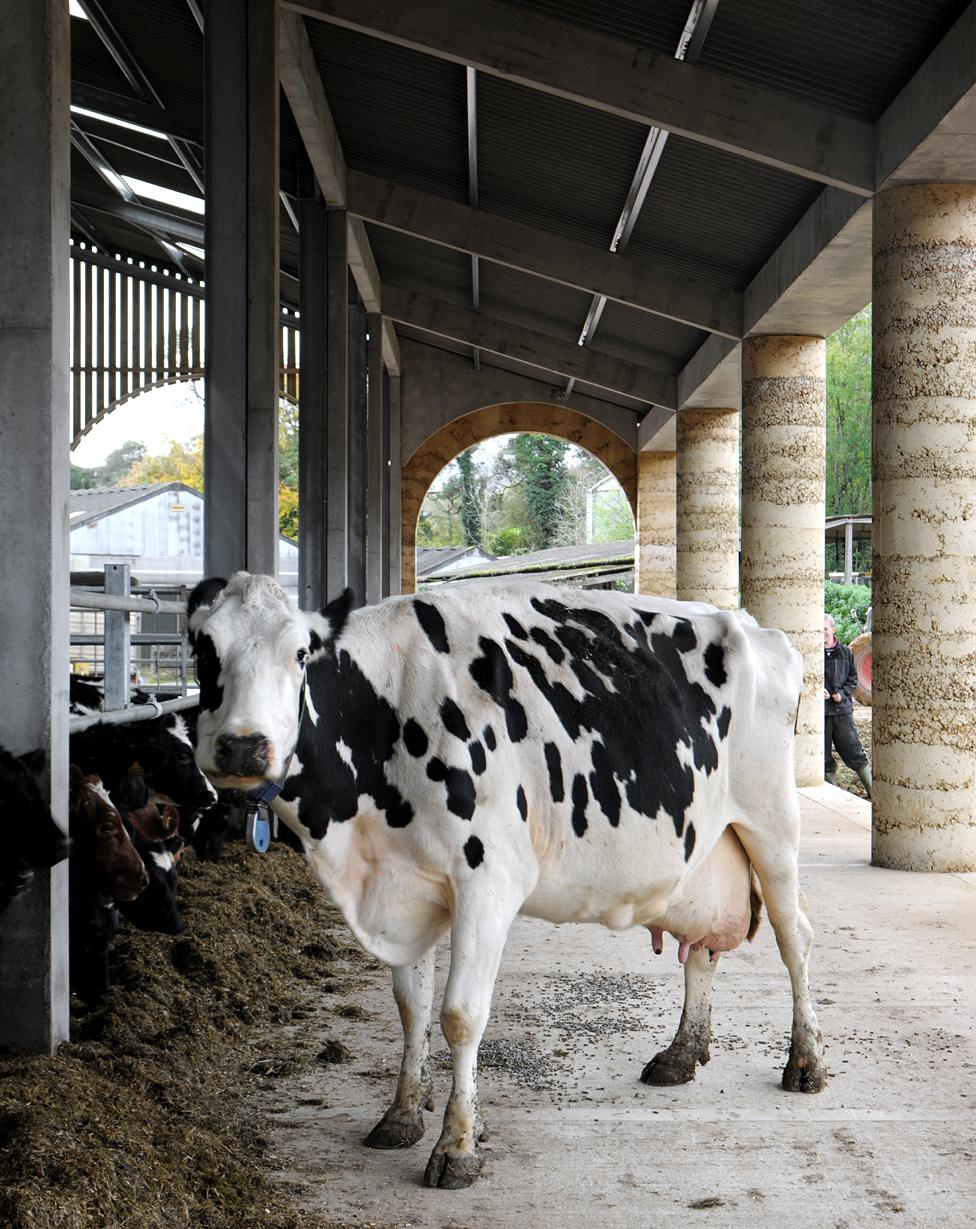

City Hall of Borgoricco, Italy - by Aldo Rossi, 1983

A world without Andrea Palladio's legacy would be a "very depressing one", says Charles Hind, chief curator of collections at the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Hind has co-curated Palladian Design: The Good, The Bad and The Unexpected, external, which runs at Riba in London until January.

Palladio reinterpreted the architecture of ancient Rome for his own time, says Hind. He believed his flexible design principles could be applied to any type of building. From the grandest to the most humble. From an imposing seat of government, to a country cowshed.

Cowshed in Somerset, UK - by Stephen Taylor, 2012

"Palladio introduced the concept that Roman architecture could be adapted to benefit all social classes," says Hind, "and that's one reason why his influence has remained more potent than any other architect."

Cowshed in Somerset, UK - by Stephen Taylor, 2012

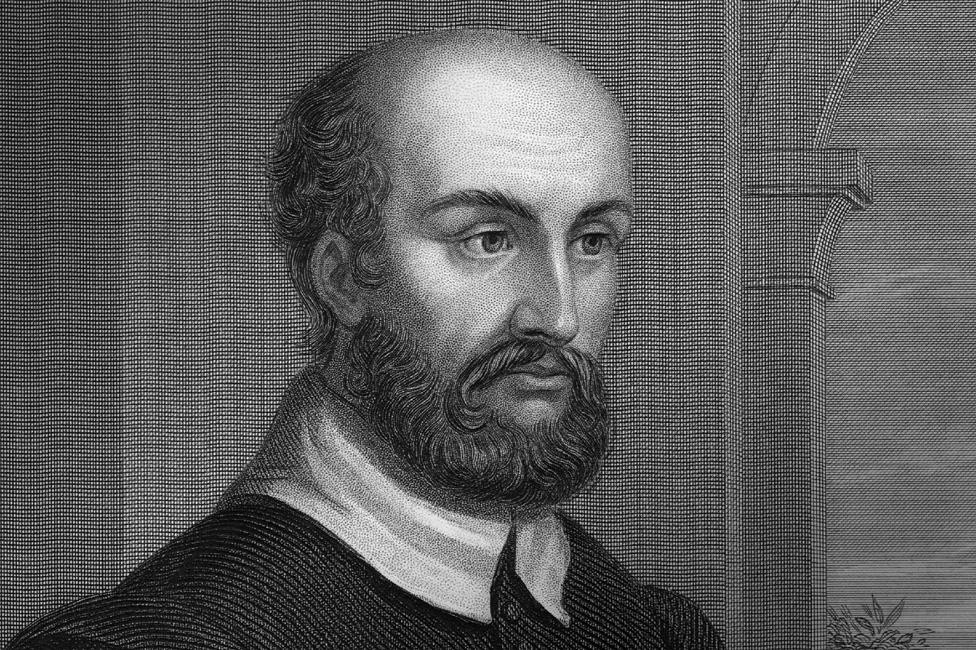

Born in 1508 in Padua in northern Italy, Andrea Palladio spent most of his adult life in the nearby city of Vicenza.

He trained as a stonemason initially, but his life was transformed when he worked for the humanist poet and scholar, Gian Giorgio Trissino, from 1538 to 1539. He was taken to Rome - which gave him the chance to study ancient ruins.

Andrea Palladio

During the Renaissance period, says Hind, very little was known about domestic architecture from the Roman Empire - much of it was yet to be discovered.

Palladio looked instead at ruins of the larger public buildings which were on show, and used this classical inspiration in his designs.

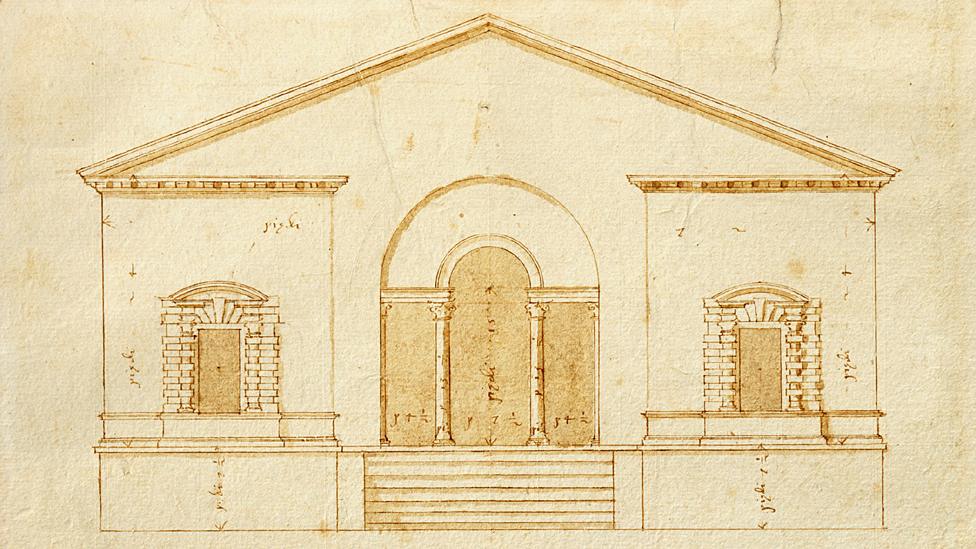

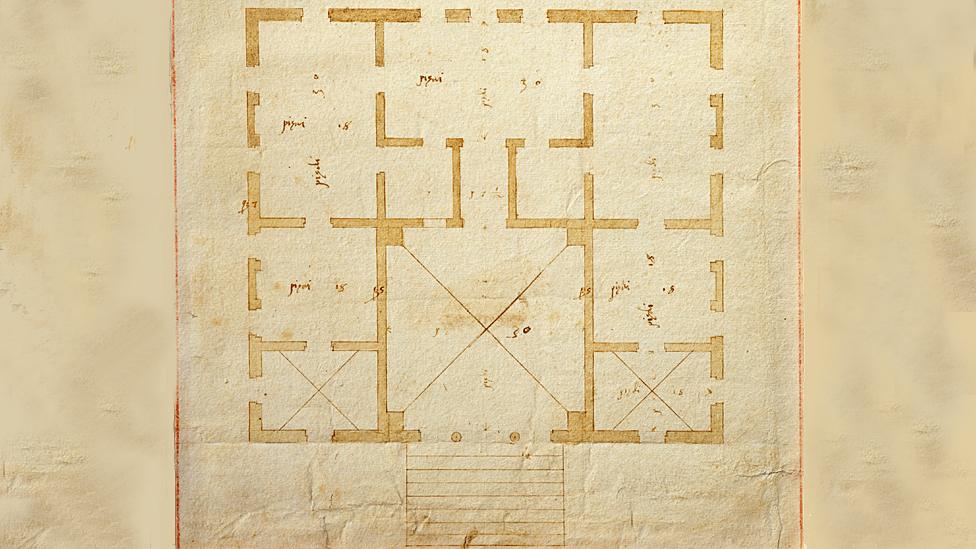

Design for Villa Valmarana, Vigardolo - by Andrea Palladio, circa 1560

Palladio became known for designing bespoke villas and country houses for aristocrats in north-east Italy - with simplicity and symmetry at the heart of each creation. His designs would have a central hall - with suites of rooms arranged around them.

He was also the first architect to integrate classical porticos - covered columned porches - into domestic housebuilding. Until then they had really only been used on religious buildings.

"Palladio reinvented the architecture of antiquity for contemporary use," Hind says.

Design for Villa Valmarana, Vigardolo - by Andrea Palladio, circa 1560

"He was enormously successful, extremely quickly."

His first solo villa was built in 1540-1, but by 1545 there were documents showing demand for people wanting villas "alla Palladiana" - in the Palladian style.

More drawings survive from Palladio's hand than all the other Italian Renaissance architects put together, thanks to two English collectors.

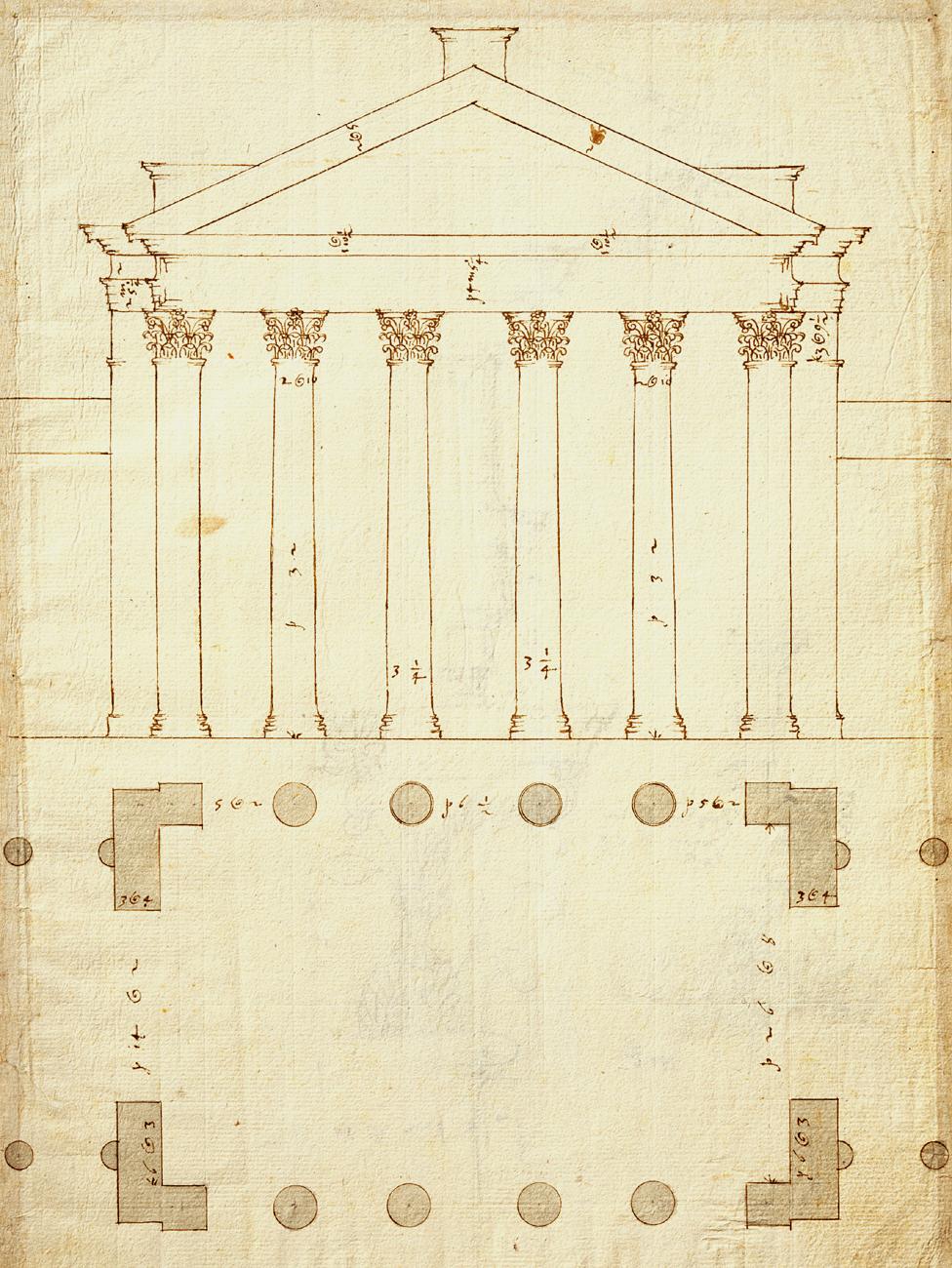

Conjectural reconstruction of the Portico of Octavia, Rome - by Andrea Palladio, circa 1560s

Inigo Jones and Lord Burlington transported them in two batches at the start of the 17th and 18th Centuries.

And it is the presence of these drawings in England, argues Hind - plus Palladio's book, The Four Books of Architecture - that were key to his long-term global influence.

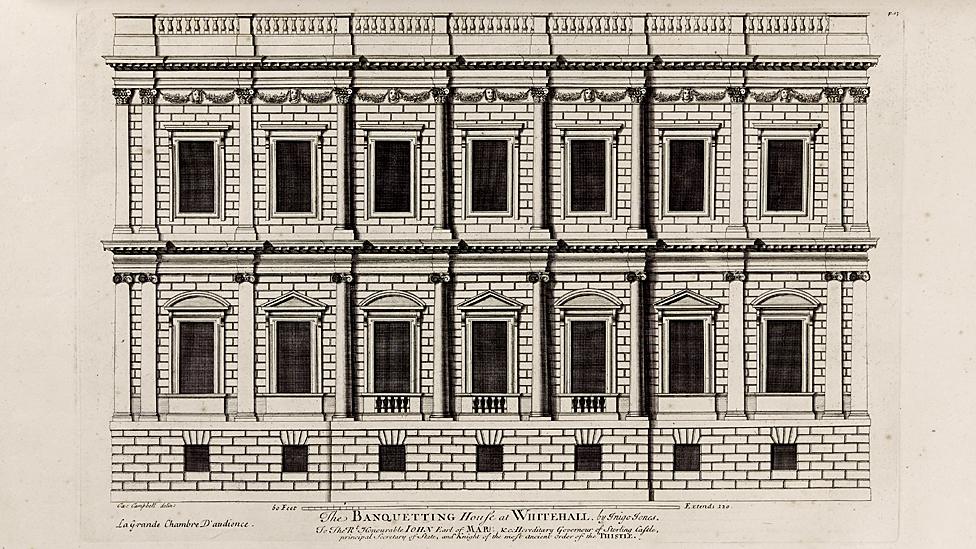

This is Inigo Jones' design for the Banqueting House on Whitehall, today one of the most visible 17th Century Palladian buildings in London.

Banqueting House, London (from Vitruvius Britannicus) - by Colen Campbell, 1715

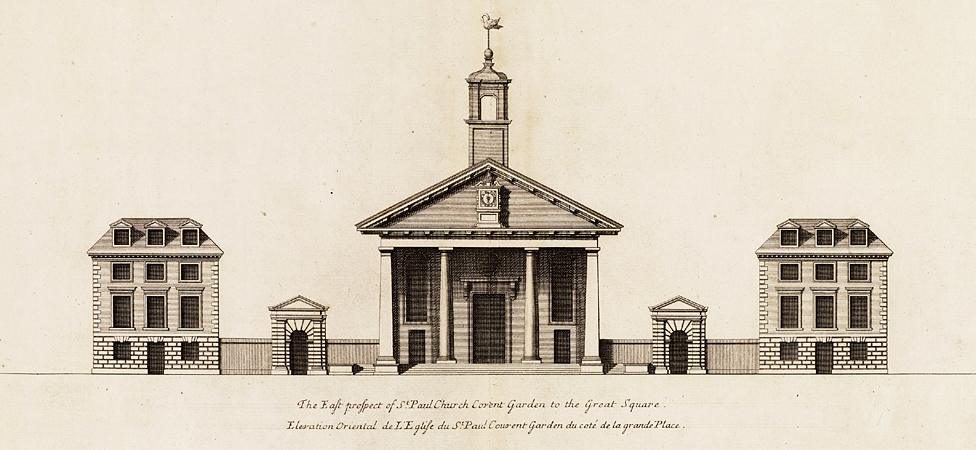

And it was Inigo Jones's adoption of Palladian principles that sparked a revolution in religious architecture. He designed St Paul's in London's Covent Garden, the first classical church in the UK. It was completed in 1633.

Front of St Paul's Church in Covent Garden, London

It resembles a Roman temple - with columns and a portico.

In the image below, crowds have gathered for election hustings. Today, it is known as the Actors' Church and provides a backdrop for street entertainers.

St Paul's Church in Covent Garden, London - depicted during election hustings in the piazza

Nearly 100 years after St Paul's was built, architect James Gibbs also embraced the Palladian style to create one of London's most prominent churches - St Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square.

Like Inigo Jones he kept the Roman temple concept, but moved the tower from the far end of the building to behind the portico at the front.

St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square, London - 1896

The style has been reproduced many hundreds of times across the world - and is still popular today.

This image, from the US in the 1930s, shows the Palladian concept at a simple level - but it is still an echo of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

Church in South Carolina, USA - 1936

In the early 18th Century, the second big collector of Palladio's drawings - Richard Boyle the 3rd Earl of Burlington - was asked to design a townhouse in London for General Wade.

Lord Burlington turned to one of Palladio's original designs - for a palace in Vicenza.

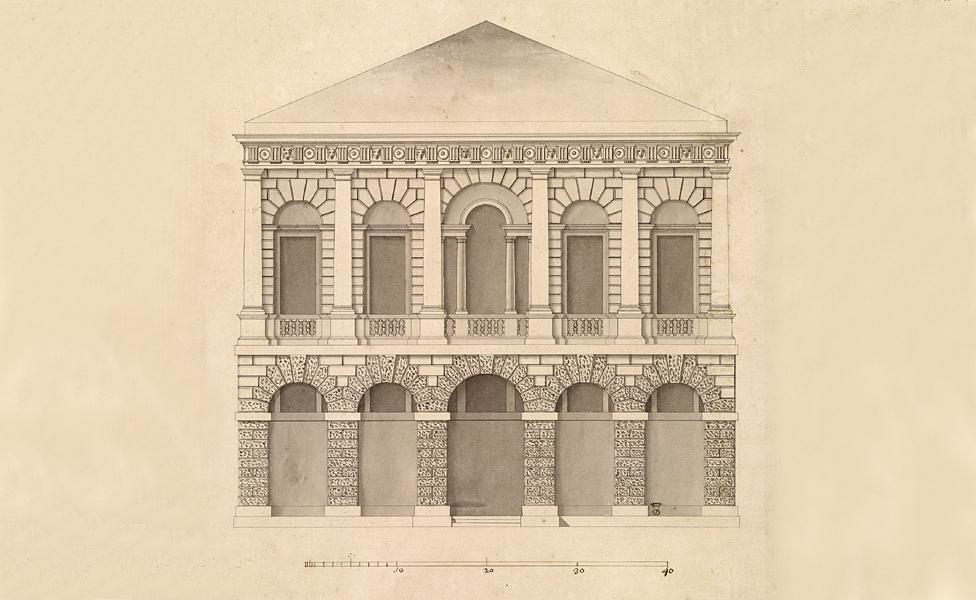

Design for a palace - by Andrea Palladio, circa 1540s

He recreated it in London - keeping strictly to Palladio's guidelines. But despite its handsome frontage, it was not a practical place to live - a mistake which, says Hind, "Andrea Palladio would not have made".

At the time, Lord Chesterfield commented that General Wade "would have been better to rent a house across the street so he could look at his house".

The building was demolished in the 1930s.

Design for Old Burlington Street, London - by Lord Burlington, 1720

Hind says that sticking strictly to Palladio's original designs did not necessarily work well for 17th Century builders in northern Europe - where the climate was cooler.

And so in time, a synthetic style developed - mostly Palladian, but blended with other elements.

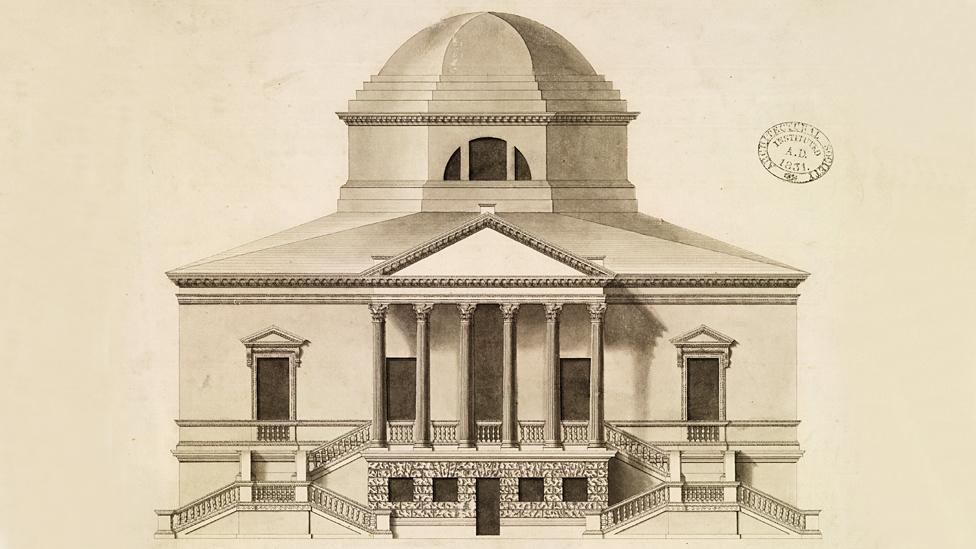

When Lord Burlington designed Chiswick House in London, it is easy to see how his inspiration came from Palladio's Villa Rotonda.

Palladio's Villa Rotonda, Vicenza, Italy

But in fact Chiswick House - which was built to store Lord Burlington's collections rather than as somewhere to live - is more of a mix of styles, with Palladian symmetry, portico and pediment, the most significant.

Chiswick House, London - by Lord Burlington, 1729

Palladian features soon became part of the standard repertoire of fashionable architecture of the time - now referred to as "Anglo-Palladianism".

The theme spread west too. In the United States it was the main building style in the 40 years leading up to the American War of Independence.

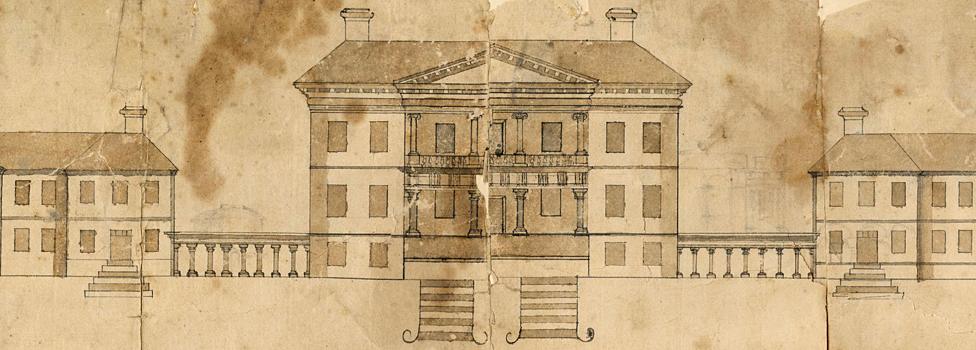

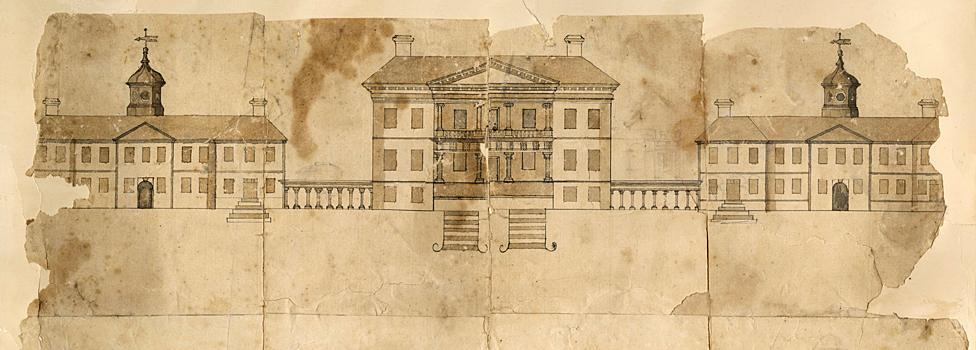

The first house to be designed in the US with a Palladian portico - a columned porch - was in South Carolina. It was the creation of plantation owner John Drayton.

It had a central block, with covered arcades stretching out to pavilions.

Design for Drayton Hall, South Carolina, USA - circa 1740

The warm climate of South Carolina is similar to northern Italy - and so well-suited to Palladian architecture in its purest form.

Double porticos - with one covered porch on top of another - were particularly popular in the southern states.

By having a raised first floor seating area, residents could enjoy a breeze - and escape gnats and other insects which rarely fly more than 15ft off the ground.

Design for Drayton Hall, South Carolina, USA - circa 1740

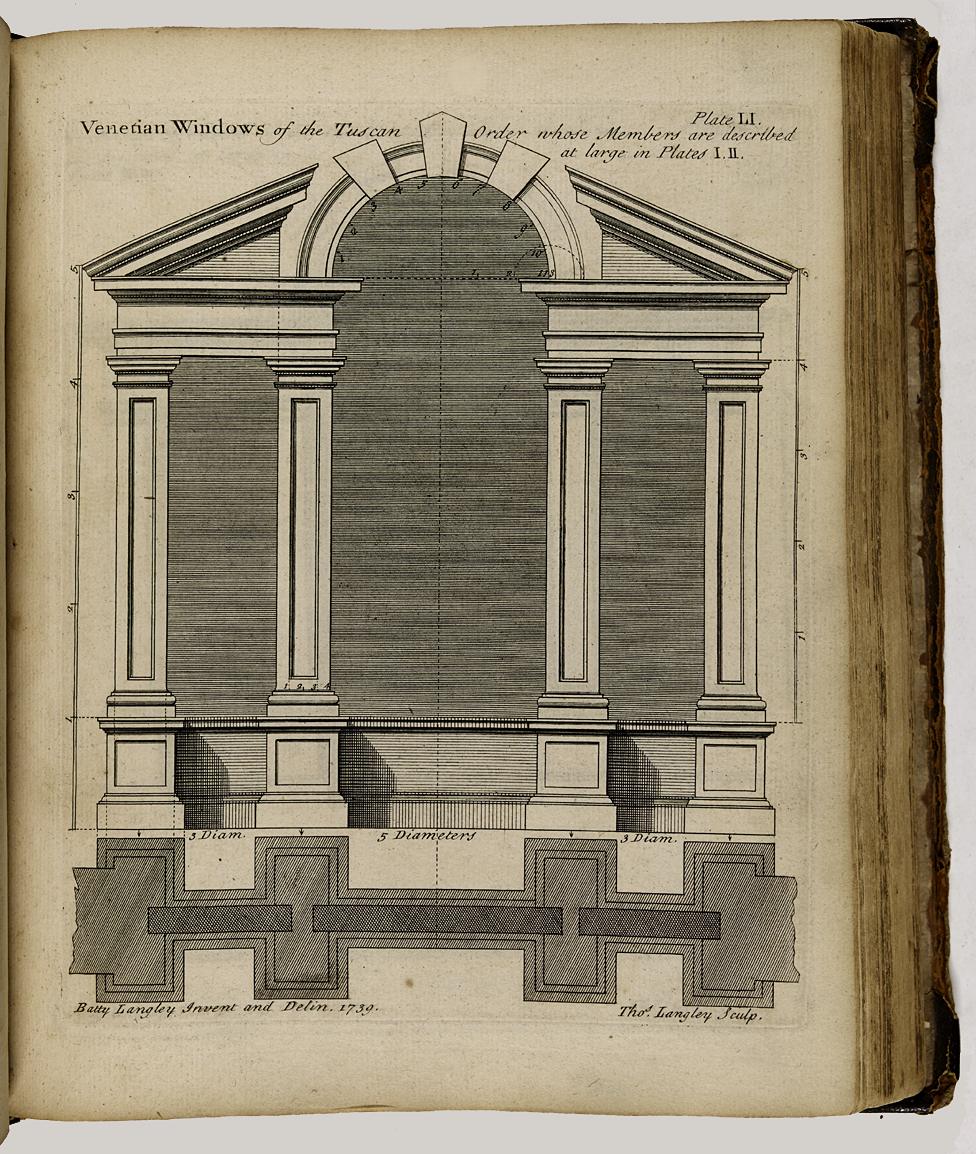

Hundreds of architectural pattern books were published from the 1720s onwards.

Hind says many of them "stretched the definition of Palladianism - almost to breaking point". It meant people could mix and match on their own homes.

A country cottage or classical vicarage could have the same elements as US President George Washington's house at Mount Vernon in Virginia.

Detail of Mount Vernon window, Virginia, USA - building completed 1778

The window above, at Mount Vernon in the United States - is identical to one which features below, in an English pattern book from 1740.

From The City and Country Builder's, and Workman's Treasury of Designs - 1740

But, as ever with fashions, Palladian popularity in the UK and Ireland was not to last. Victorians preferred more elaborate Gothic and classical Greek styles.

It took until the start of the 20th Century, into the Edwardian era, before there was a full-blown renaissance of Andrea Palladio's symmetrical concepts.

Artwork of Stormont, Belfast, Northern Ireland, by architect Arnold Thornely - 1932

In Belfast, the Stormont parliament building - which was built from the late 1920s after the partition of Ireland - has strong Palladian elements, with its symmetrical front, central portico and pediment.

"Palladianism breathes permanence, deliberation and an Olympian calm," says Hind. It suggests "we're going to stay here".

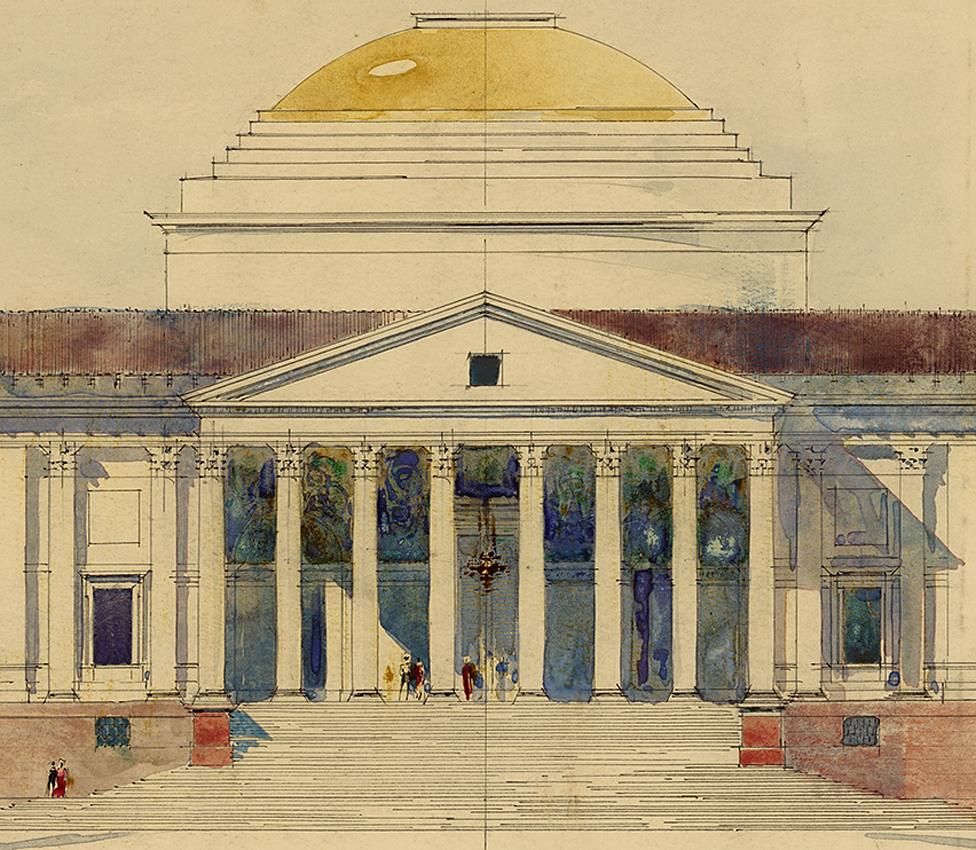

More symmetry permeates this 1912 proposed design for the Viceroy's House in New Delhi, India.

Design for the Viceroy's House, New Delhi - by Edwin Lutyens - 1912

Edwin Lutyens' initial plan was for a very grand Palladian country house.

Design for the Viceroy's House, New Delhi - by Edwin Lutyens - 1912

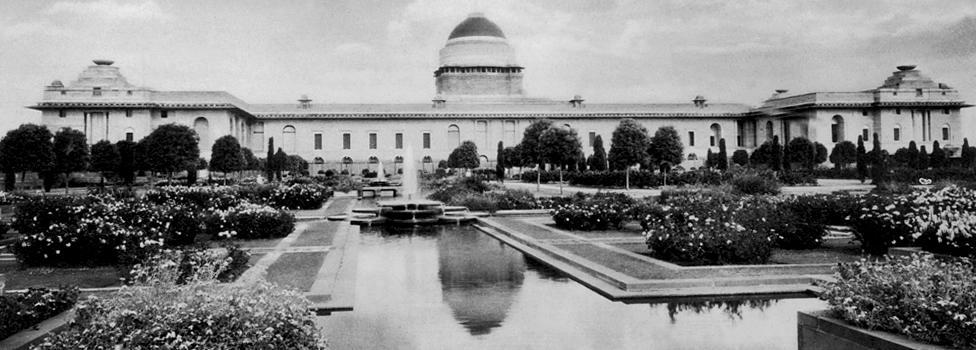

But the design was eventually changed to include more Indian elements. It was completed in 1929.

Viceroy's House, Delhi - 1930

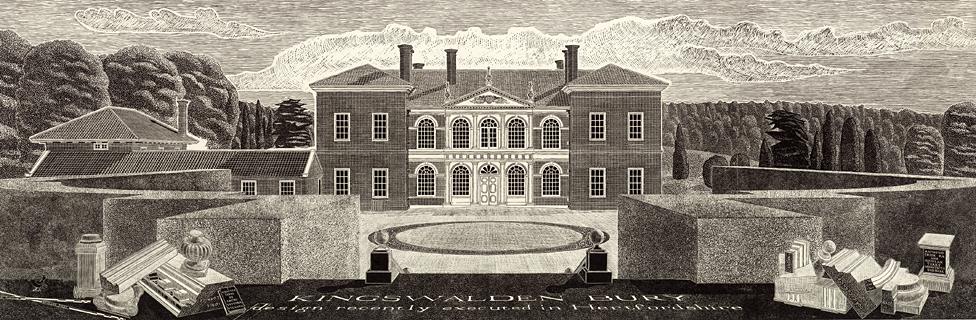

The Palladian revival continued through the 20th Century. In the UK it offered a way of keeping a sense of grandeur, even when landowners were downsizing from a larger property.

Kings Walden Bury in Essex was built in the late 1960s.

Hind says the clients demolished a large unwieldy Victorian house, but wanted to keep their chandeliers which needed specific ceiling heights. Hence they settled on Palladianism.

Kings Walden Bury, by Erith and Terry - completed 1971

Across the Atlantic, the USA has never really stopped using Palladianism as an architectural style.

"It gives people a sense of creating history," says Hind.

Palladio incorporated elements of the Venetian local style into his architecture 500 years ago - and in the 21st Century, Chadsworth Cottage in North Carolina does the same.

Built on a coast prone to hurricanes - where homes must be built on stilts so that storm water can rush underneath - the stairs and wooden slats which hide the stilts supporting this house resemble the base of a temple or grand house.

Chadsworth Cottage, Figure Eight Island, North Carolina, USA - by Christine Franck, 2005

While perhaps not obvious at first glance, Palladian rules have been used in more modern architectural styles over the past 100 years.

Palladian elements of symmetry, pediment and the arrangement of windows can be seen in this 1919 design for the Lister County Court House in Sweden.

Lister Court House, by Erik Asplund - 1919

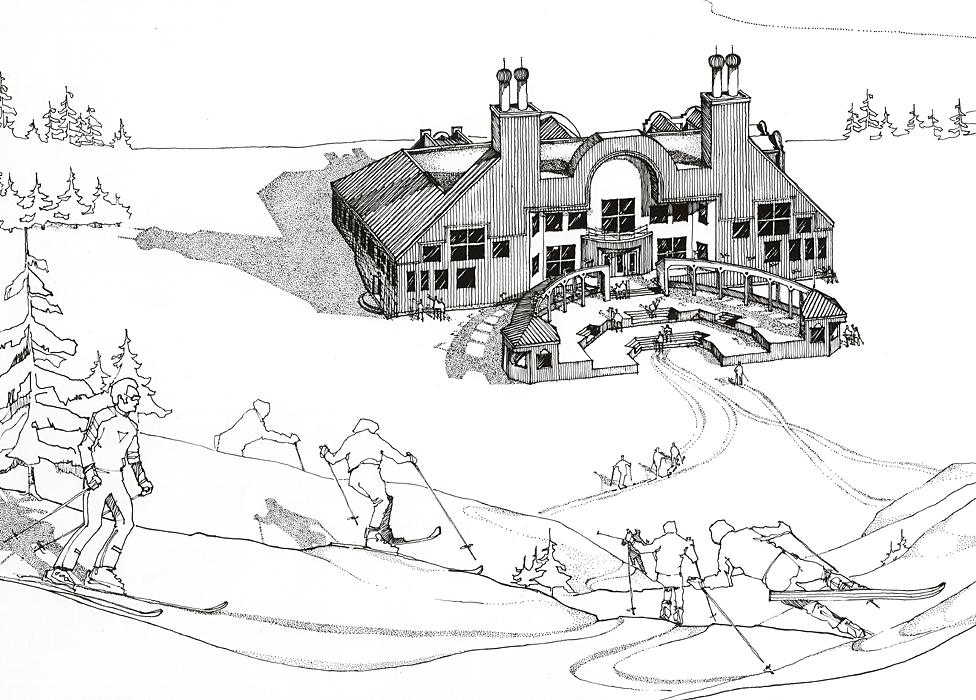

And this ski lodge in Canada, designed and built in the 1970s, purports to have classical Palladian elements - the symmetrical front and curved arcades.

But behind that "it's all a facade, a joke", says Hind. "The space behind it bears no relationship to what's in front."

Pavillion Soixante-Dix, St Sauveur, Canada, by P Rose/P Lanken/J Righter - completed 1977

The last section of the Riba exhibition looks at what it calls "abstract Palladianism" - where modern architects claim to have still been influenced by Palladio.

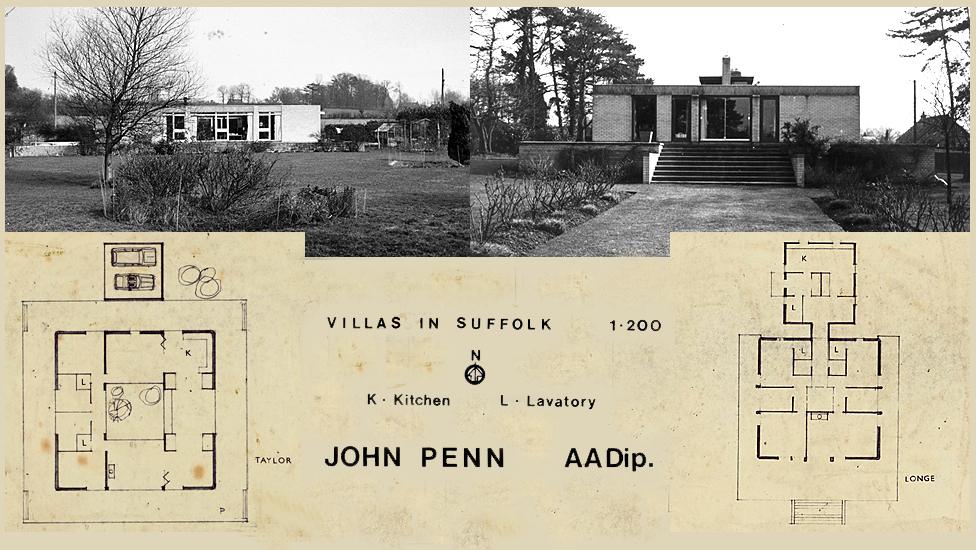

In the 1960s, John Penn created these bungalows in eastern England. On raised platforms, the room layouts follow Palladian principles, with a central space and rooms laid out around.

Villas in Suffolk, UK, by John Penn - constructed between 1962-69

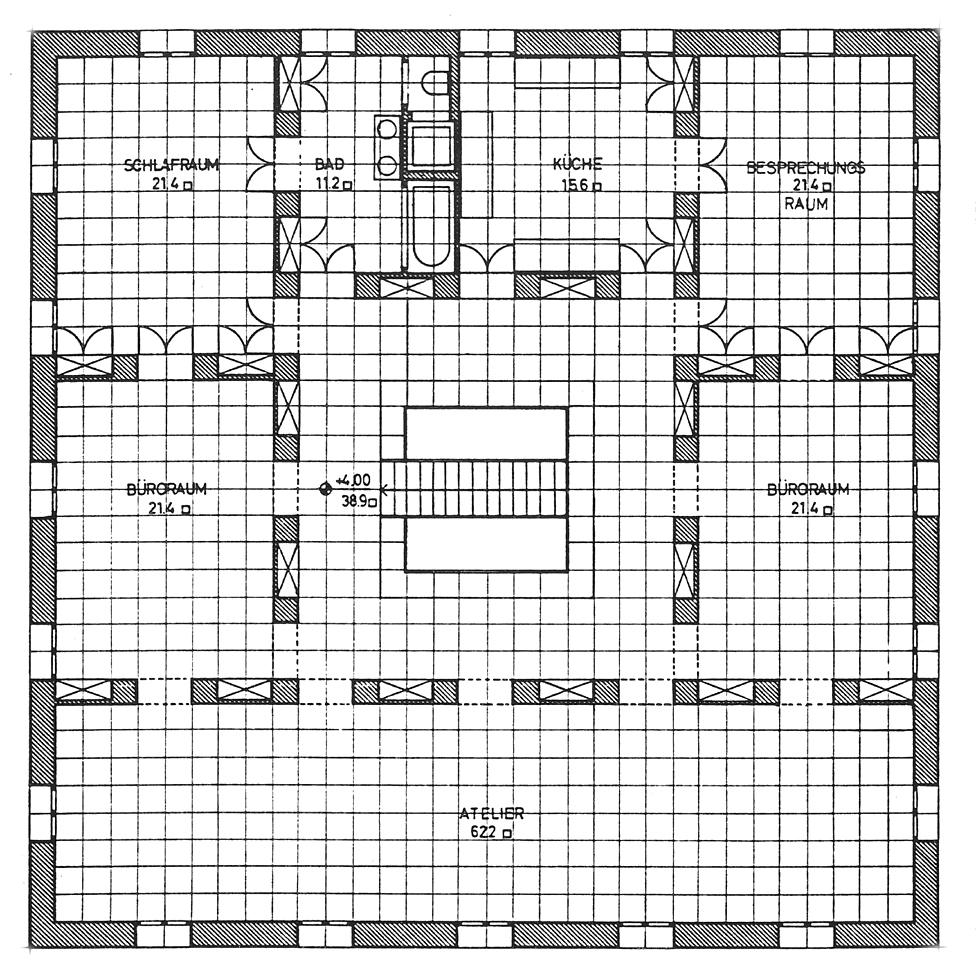

Finally this house - Glashutte at Eifel in western Germany - "is a rectangular box with each facade symmetrical", says Hind,

The rooms inside are laid out around a central hall and staircase.

It has been stripped of all Palladian ornament - and yet, says Hind, "you read it as a classical building".

Glashutte, Eifel, Germany, by Oswald Mathias Ungers - completed 1988

Glashutte, Eifel, Germany, by Oswald Mathias Ungers - completed 1988

Palladian Design: The Good, The Bad and The Unexpected, external - can be seen at the Royal Institute of British Architects in central London until 9 January 2016. Admission free.

All images subject to copyright. No reproduction without permission.